This is how I like to remember them, young and in love, the way they still looked when I was a child, though by then they were already starting to show visible signs of wear and tear. I didn’t come along until they’d been together for eight years, at which point they knew in their bones that married life–adult life–was wholly unlike what they’d envisioned.

This is how I like to remember them, young and in love, the way they still looked when I was a child, though by then they were already starting to show visible signs of wear and tear. I didn’t come along until they’d been together for eight years, at which point they knew in their bones that married life–adult life–was wholly unlike what they’d envisioned.

My parents knew little of adult life when this snapshot was taken on the front porch of the ramshackle house where my mother grew up. All they knew was that they very much wanted to get married and start a family. The Great Depression and World War II were still fresh in their memories, and they took it for granted–not unreasonably–that the future, whatever it might hold in store for them, had to be better than that.

Some of it was and some of it wasn’t. Their marriage was stormy, enough so that they actually separated for a time. But small-town people who tied the knot in 1948 didn’t divorce save for the gravest and most intolerable of causes, so they gritted their teeth, stuck it out, raised two boys, and eventually discovered that they couldn’t live without each other, at least not very well.

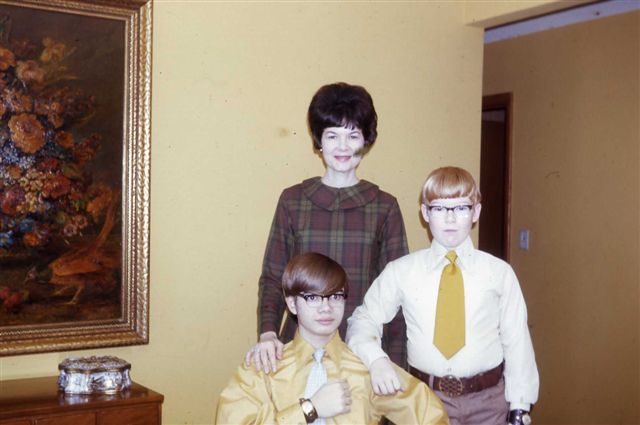

This is how they looked in middle age, just before illness started to carve its long furrows on their faces. They still liked to sit together on porch swings–they always would–and there was no longer any doubt in their minds that they would spend the rest of their lives together, just as there is no doubt in my mind that they were right to do so.

This is how they looked in middle age, just before illness started to carve its long furrows on their faces. They still liked to sit together on porch swings–they always would–and there was no longer any doubt in their minds that they would spend the rest of their lives together, just as there is no doubt in my mind that they were right to do so.

You can’t imagine what it feels like to outlive your parents until you do, any more than you can imagine what it feels like to be married until you are. My father died of cancer in 1998, having suffered greatly for a long time. My mother lived on for fourteen more years, the first dozen of which were unexpectedly happy, the last two grievously hard (though not without periods of joy). I wouldn’t have wanted either of them to have lived an hour longer than they did. Yet no day goes by when I don’t find myself missing them both, sometimes fleetingly and sometimes piercingly.

As I headed down to Broadway the other night to see a show, I took out my cellphone and called up my brother in Smalltown, U.S.A. He was working at my mother’s house, remodeling the family room in preparation for the day when he and my sister-in-law will move in.

“What’s up?” he asked.

“What’s up?” he asked.

“Nothing,” I said. “Nothing in particular. No news. I just felt like chatting.” And so we did, talking idly and cheerfully of nothing in particular.

Then it hit me. “You know what?” I said. “I always used to call Mom at this time of day, right when I was going to a show. Now I’m calling you instead.”

Neither one of us spoke for a long moment. Then we started chatting again.

* * *

Nancy LaMott sings “Some Other Time,” by Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green:

Archives for February 18, 2013

TT: Just because

An extremely rare kinescope of George Sanders singing and playing Cole Porter’s “Thank You So Much, Mrs. Lowsborough-Goodby” and “C’est Magnifique” on Ford Star Jubilee: You’re the Top, originally telecast on CBS on Oct. 6, 1956:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“You always have a tendency to add. But one must be able to subtract too. It’s not enough to integrate, you must also disintegrate. That’s the way life is. That’s philosophy. That’s science. That’s progress, civilization.”

Eugène Ionesco, The Lesson