You probably won’t recognize Claire P. Gordon‘s name unless you happen to know a great deal about swing-era jazz, and even then it may not ring a bell. She helped Rex Stewart, Duke Ellington’s longtime cornet player, and Marshal Royal, the alto saxophonist who served as Count Basie’s “straw boss,” write their autobiographies, both of which are priceless historical documents that also happen to be enormously readable.

You probably won’t recognize Claire P. Gordon‘s name unless you happen to know a great deal about swing-era jazz, and even then it may not ring a bell. She helped Rex Stewart, Duke Ellington’s longtime cornet player, and Marshal Royal, the alto saxophonist who served as Count Basie’s “straw boss,” write their autobiographies, both of which are priceless historical documents that also happen to be enormously readable.

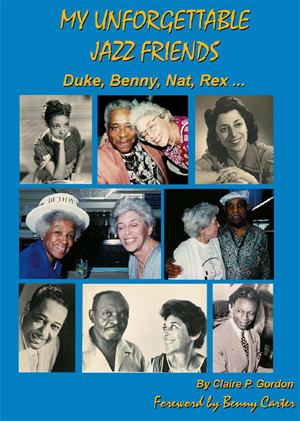

I knew about both of those books, but it wasn’t until a couple of months ago that I was made aware of the fact that Gordon had also written a memoir of her own, a book called My Unforgettable Jazz Friends: Duke, Benny, Nat, Rex… A mutual friend told me about her book, going on to say that it might be of interest to me in my capacity as a jazz biographer. Indeed it was–very much so–but I ended up reading My Unforgettable Jazz Friends more for pleasure than anything else.

Gordon grew up in Los Angeles at a time when that city was a major center of jazz-related activity, and she plunged herself into the black jazz scene when she was a teenager, too innocent at first to realize how far removed it was from her sheltered existence and how extraordinary it was that a young white girl should have longed to explore that strange new world. Almost before she knew it, she was friendly with Benny Carter, Nat Cole, Meade “Lux” Lewis, Maxine Sullivan, and–above all–Duke Ellington and the members of his band, who spent most of 1941 in Hollywood.

My Unforgettable Jazz Friends tells the unlikely but true tale of how Gordon got to know these great artists, and what they were like both on and off the bandstand. The style is perfectly straightforward, as if she were chatting with you over a cup of coffee, and the stories are both candid and illuminating. Though the book’s gossip value is far from inconsiderable, I found Gordon herself to be as interesting as her famous friends. How amazing that she did what she did when she did it, and that she’s still around more than seven decades later to tell us about it! Would that more jazz fans of her generation had taken the time to set down their memories in so engaging a way.

My Unforgettable Jazz Friends tells the unlikely but true tale of how Gordon got to know these great artists, and what they were like both on and off the bandstand. The style is perfectly straightforward, as if she were chatting with you over a cup of coffee, and the stories are both candid and illuminating. Though the book’s gossip value is far from inconsiderable, I found Gordon herself to be as interesting as her famous friends. How amazing that she did what she did when she did it, and that she’s still around more than seven decades later to tell us about it! Would that more jazz fans of her generation had taken the time to set down their memories in so engaging a way.

You can order a copy of My Unforgettable Jazz Friends here. If the popular music of the Forties means as much to you as it does to me, then I strongly suggest that you do so.

Archives for January 2013

TT: Snapshot

A rare TV interview with Christopher Isherwood:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“I like work; it fascinates me. I can sit and look at it for hours.”

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat

TT: Lookback

From 2004:

I find it difficult to wave the Luddite banner with any real enthusiasm. Of course recorded sound is a mixed blessing: we pay a price for its ubiquity, and that price is getting steeper. But all blessings are mixed, and it is up to us to make the best of them. If I had to choose between the continued survival of the Podunk Philharmonic and the existence of the recordings of Louis Armstrong, I’d probably take a deep breath and vote for Louis–but it’s our job as music lovers to make sure that such choices never become necessary….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“But I have long thought that if you knew a column of advertisements by heart, you could achieve unexpected felicities with them. You can get a happy quotation anywhere if you have the eye.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., letter to Harold Laski, May 31, 1923

TT: Toys in the attic

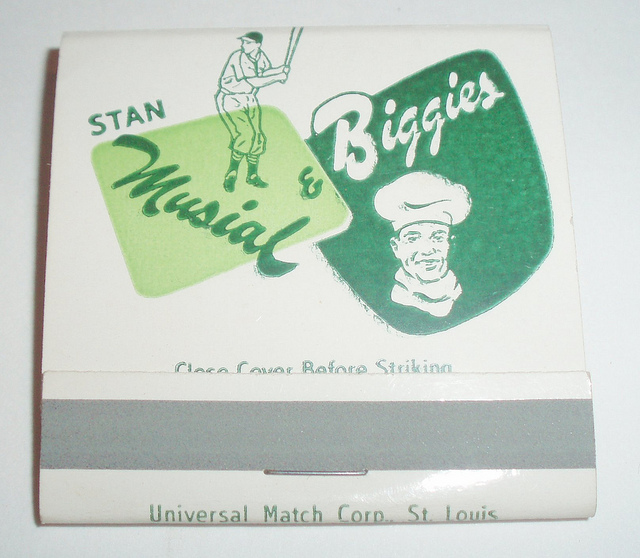

I don’t know anything about baseball, but I do know who Stan Musial was. Not only did I meet him as a boy on my lone visit to the old Busch Stadium, but I even owned a baseball that he autographed, courtesy of my father, who ate as often as possible (which wasn’t very often) at Stan Musial and Biggie’s, the St. Louis steakhouse that he co-owned.

The baseball, not surprisingly, disappeared long ago, together with my fleeting interest in sports, which was over almost before it started. As for Stan the Man, I hadn’t thought about him for years until I happened to read his obituary the other day. He belonged to another part of my life, one that was stable, secure, and constant.

The baseball, not surprisingly, disappeared long ago, together with my fleeting interest in sports, which was over almost before it started. As for Stan the Man, I hadn’t thought about him for years until I happened to read his obituary the other day. He belonged to another part of my life, one that was stable, secure, and constant.

The present part of my life is none of these things. Now I lead the life of a wanderer whose job drives him from place to place. To be sure, I have a home, but I’m rarely there, though I did spend a few consecutive nights in my New York apartment toward the end of 2012. Since then I’ve been in Florida, where Mrs. T and I just spent three weeks in a cottage on the Gulf of Mexico. On Saturday we pulled up stakes, drove across Alligator Alley to Coral Gables, and checked into the Biltmore Hotel for a three-night stay. Yesterday I saw a matinee of Hamlet, then spent eight hours working on my Duke Ellington biography while Mrs. T watched Skyfall on pay-per-view. Tomorrow we set out again, this time for Orlando.

One of my blogger friends recently wrote about home and its meaning:

My brother is selling the house we grew up in. I wasn’t quite three when we moved in, in 1955, the year of his birth. My earliest memory is the grass in the neighbor’s backyard resembling a field of wheat. I haven’t lived there in forty years. I’ve never paid the property taxes or called the plumber, but the place remains as vivid as a road map. I still think of a real house as one built of brick. Upstairs in my room I read Hamlet and The Adventures of Augie March for the first time, and clipped Eric Hoffer’s column from the newspaper. When I walked in the back door on Nov. 22, 1963, I saw my mother, two rooms away, crying in front of the television. Even in my alienated days it stayed, in some primal sense, home.

Our experiences are closely similar, except that my friend feels more at ease with the coming loss of the place where he comes from. “Growing up means learning to carry home around with us, like nomads,” he writes. “That strangers may soon be living in our old house is inevitable and right.” I could never feel that way, pehaps because I really do live like a nomad. It is a profound comfort to me to know that my brother and his wife will soon be moving into our childhood home, which my mother’s death left empty. I can scarcely imagine what it must mean to him.

Had life left me to my own devices, I think it’s possible that I might have remained in Smalltown, U.S.A., or at the very least set down roots in Kansas City, where I lived for eight years and in which I once gave serious thought to staying put. I’m not a wanderer by nature: I miss Smalltown and Kansas City and the joys of staying in one place, just as I miss my mother and father. But it didn’t work out that way, and since I’ve always found it possible to embrace the present and those who inhabit it, I am, for the most part, a passably happy man.

Had life left me to my own devices, I think it’s possible that I might have remained in Smalltown, U.S.A., or at the very least set down roots in Kansas City, where I lived for eight years and in which I once gave serious thought to staying put. I’m not a wanderer by nature: I miss Smalltown and Kansas City and the joys of staying in one place, just as I miss my mother and father. But it didn’t work out that way, and since I’ve always found it possible to embrace the present and those who inhabit it, I am, for the most part, a passably happy man.

In 1989 I published an essay called “Elegy for the Woodchopper” (it’s in the Teachout Reader) in which I described what it was like to spend a few days riding the bus with Woody Herman and his band. One of the musicians, a trumpeter named Mark Lewis whose father had played with Herman more than forty years earlier, told me how he felt about living out of a suitcase:

The road is the same thing every day. You don’t have much time to yourself. You eat bad food a lot of the time. You’re stuck on a bus eight hours a day. You wash your underwear in the sink. When you get sick, there’s nothing you can do but ride the bus and play the gigs and feel rotten all the time. But I like it. I really do. I know it sounds crazy, but there’s a freshness to our work that makes it worthwhile, especially when we get a young crowd. That’s what we look forward to. They make us want to play.

Back then I had no real understanding of what Mark was talking about. Now I do. Yes, my life on the road is infinitely easier than his was, but in essence it is the same, and for the most part I continue to find it not merely tolerable but self-renewing. I love what I do, and I love it even more when Mrs. T travels with me. But I also loved living in one place, and the older I grow, the surer I am that a time will come when I long to do it again.

Back then I had no real understanding of what Mark was talking about. Now I do. Yes, my life on the road is infinitely easier than his was, but in essence it is the same, and for the most part I continue to find it not merely tolerable but self-renewing. I love what I do, and I love it even more when Mrs. T travels with me. But I also loved living in one place, and the older I grow, the surer I am that a time will come when I long to do it again.

Whether or not I’ll get a chance to do so is another matter altogether. It may be that my destiny is to continue roaming the land and living out of a suitcase. If it is, I’ll make the best of it. I always do. Very little of my Duke Ellington biography, after all, was written at my desk in New York: I wrote most of it in rented cottages and hotel rooms and at the MacDowell Colony, and I don’t think it’s the worse for that. What I wonder is whether I am.

The day after Harry Truman finally returned home to Independence, Missouri, a reporter asked him what he planned to do first. “Carry the grips up to the attic,” he replied. It’s a wonderful line, one that says everything about what it means to come from a place like Missouri. The catch, of course, is that you have to have an attic, a place where you can store a baseball signed by Stan Musial and know that it’ll still be there when, a half century later, you feel like taking it out and looking at it.

TT: Just because

Wes Montgomery plays “Twisted Blues”:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“When you’re coming to an end, you don’t take any comfort in your achievements. What matters is how it went with women and how it went with children. That’s what becomes important. The terrible symmetry is that men don’t tend to blame themselves–it’s always someone else’s fault. And women tend to blame themselves. But, then, at the very end, it’s the men who start blaming themselves and the women stop blaming themselves. And that’s why they’re happier.”

Martin Amis (quoted in The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 28, 2012)