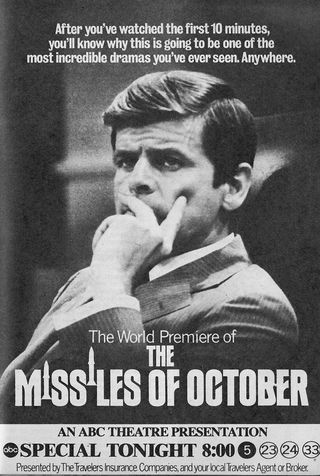

My Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, which normally runs every other Friday, is being published in today’s paper to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis. In it I write about The Missiles of October, the 1974 TV docudrama about the crisis. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Most historians regard docudramas with extreme suspicion–as well they should. From “Inherit the Wind” to Oliver Stone’s “JFK” to “Stuff Happens,” David Hare’s 2004 play about Gulf War II, most of the best-known examples of the genre, in which a screenwriter or playwright takes a well-documented historical event and fictionalizes it, are tendentious to the point of outright falsity. But the rotten barrel of docudrama also contains a few good apples, and one of them, “The Missiles of October,” deserves to be celebrated this week, a half-century after the Cuban Missile Crisis was set in motion by the Pentagon’s discovery that the Soviet Union was moving nuclear missiles into Cuba.

Most historians regard docudramas with extreme suspicion–as well they should. From “Inherit the Wind” to Oliver Stone’s “JFK” to “Stuff Happens,” David Hare’s 2004 play about Gulf War II, most of the best-known examples of the genre, in which a screenwriter or playwright takes a well-documented historical event and fictionalizes it, are tendentious to the point of outright falsity. But the rotten barrel of docudrama also contains a few good apples, and one of them, “The Missiles of October,” deserves to be celebrated this week, a half-century after the Cuban Missile Crisis was set in motion by the Pentagon’s discovery that the Soviet Union was moving nuclear missiles into Cuba.

Written by Stanley R. Greenberg and telecast on ABC in 1974, “The Missiles of October,” which is now available on DVD and on YouTube, was a new type of full-length prime-time TV docudrama. Prior to that time, network TV had dabbled with some frequency in the fictionalization of history, most notably with Abby Mann’s “Judgment at Nuremberg,” which was originally written in 1959 for “Playhouse 90.” But Mr. Greenberg, unlike Mr. Mann and the vast majority of his predecessors, tried to stick as closely as possible to the facts as they were known at the time. Not only did he base his script on “Thirteen Days,” Bobby Kennedy’s posthumously published memoir of the crisis, but “The Missiles of October” opens with an announcement that leaves the viewer in no doubt of his intention to play it straight: “The names we use are real. The action is based upon the historical record as drawn from reportage, academic studies, eyewitness accounts, and official documents.”

Mr. Greenberg’s determination to hew as closely as possible to the record explains in large part why “The Missiles of October” is so much more believable than the Kevin Costner vehicle “Thirteen Days,” the 2000 film version of the same story. Scarcely less central to its impact, though, is the bare-bones way in which it was produced. Anthony Page, the director, shot “The Missiles of October” not on film but videotape, thus giving it a you-are-there crispness, and used dirt-plain interior sets reminiscent of what you might have expected to see in a medium-to-low-budget stage play–or a classic ’50s live-TV drama…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Watch The Missiles of October:

President Kennedy’s actual 1962 Oval Office speech, in which he told viewers that the Soviet Union was moving nuclear weapons into Cuba:

Archives for 2012

TT: Lookback

From 2005:

From 2005:

Was it a great performance, or merely a great occasion? Falstaff, after all, is no knockabout farce but one of Western art’s most searching commentaries on the vanity of human wishes, no less so because it says what it has to say with a smile. What makes Verdi’s Falstaff immortal is the comic finality with which his remaining delusions of potency are dispelled–and the nobleman’s grace with which he accepts his reversal of fortune. Verdi, who was seventy-nine years old when he completed Falstaff, understood such matters in his bones, which is why Falstaff is the most Shakespearean of all operas. Sir John may be a fool to chase after Alice and Meg, but if he is, so are we all…

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“I suppose there is no word quite as evocative in the English language as ‘home,’ especially if you don’t have one.”

Richard Burton, diary entry, Aug. 22, 1969

TT: Escape

Mrs. T and I have made our post-show getaway. We’ll be somewhere else all this week, but the blog–as always–will continue. See you when we see you.

TT: Gone in sixty seconds

My father owned three Polaroid cameras and bought a fourth one for me when I was a boy. I thought of them–and of him–when I read Christopher Bonanos’ Instant: The Story of Polaroid, a newly published book about Edwin H. Land, the inventor of the first “instant camera,” and the once-powerful, now-forgotten corporation that he created.

My father owned three Polaroid cameras and bought a fourth one for me when I was a boy. I thought of them–and of him–when I read Christopher Bonanos’ Instant: The Story of Polaroid, a newly published book about Edwin H. Land, the inventor of the first “instant camera,” and the once-powerful, now-forgotten corporation that he created.

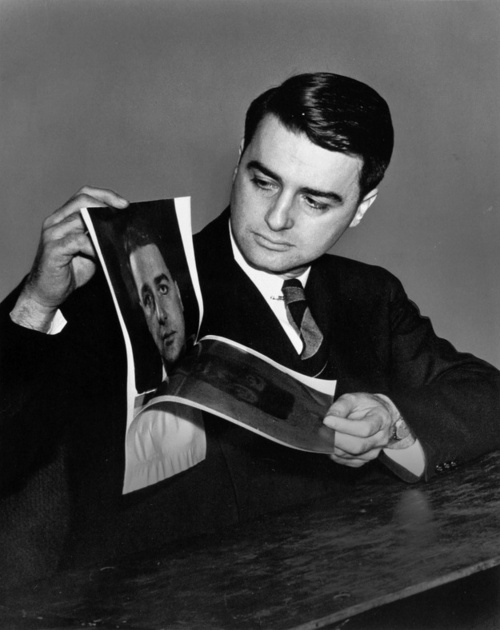

Today’s smartphone-addicted youngsters can’t begin to fathom the cultural impact of the Polaroid Model 95 camera, which took sepia-toned photographs that developed themselves in sixty seconds. When Land gave the first public demonstration of his invention in 1947, taking a picture of himself and displaying it to the audience a minute later, the audience gasped. What happened next, says Bonanos, was very nearly as astonishing:

The next morning, the shot of Land revealing his own mug got big play in the New York Times, along with an appreciative editorial. Newspapers all over the county ran the story. The following Monday, it was the “Picture of the Week” in Life magazine, then the alpha and omega of American photojournalism….

Remember that amateur photography, in 1947, had come along only a modest amount since [George] Eastman’s first film in 1888. Yes, the cameras were better and more versatile, and color was becoming widely available. When it came time to process your pictures, however, you had two choices: build yourself a darkroom, or get your film to a lab. If you didn’t live in a big city, you were probably mailing your film back to Kodak, same as in 1888. The leap to Polaroid was like replacing a messenger on horseback with your first telephone. “There is nothing like this in the history of photograph” was how the unsigned Times editorial put it.

It stands to reason that a natural-born geek like me would have been fascinated by the technological magic of Polaroid’s self-developing process, and so I was. Alas, I had no visual sense–it wasn’t until adulthood that I learned how to use my eyes in anything more than a superficial way–and I’ve never felt much inclined to preserve corporeal souvenirs of my past life, not even the carefully posed vacation snapshots that my father took by the truckload. The Polaroid Swinger, a low-priced model that came out in 1965, was the only camera that I’ve ever owned, or wanted to own.

It stands to reason that a natural-born geek like me would have been fascinated by the technological magic of Polaroid’s self-developing process, and so I was. Alas, I had no visual sense–it wasn’t until adulthood that I learned how to use my eyes in anything more than a superficial way–and I’ve never felt much inclined to preserve corporeal souvenirs of my past life, not even the carefully posed vacation snapshots that my father took by the truckload. The Polaroid Swinger, a low-priced model that came out in 1965, was the only camera that I’ve ever owned, or wanted to own.

No doubt part of its irresistible appeal to me lay in the youth-oriented TV commercials that introduced the Swinger (as well as a very young Ali MacGraw) to the American public:

That said, I also suspect that when I put the Swinger at the top of my Christmas list for 1966, what I really had in mind was to emulate my father, a deep-voiced, gadget-loving man’s man whom I admired without reserve but to whom I never succeeded in becoming close. The problem was that we had little in common save for a deep-seated belief in the virtue of professionalism. “A thing worth doing, son, is worth doing right,” he told me over and over again, not realizing that the two of us had radically different notions of what was worth doing.

When I was ten, though, I still believed that my father knew everything and could do anything, and it must have occurred to me, consciously or not, that it would please him if I tried to do something that he himself enjoyed. So I asked for and received a Swinger, and spent the next couple of years earnestly taking my own carefully posed vacation snapshots, none of which, so far as I know, have survived.

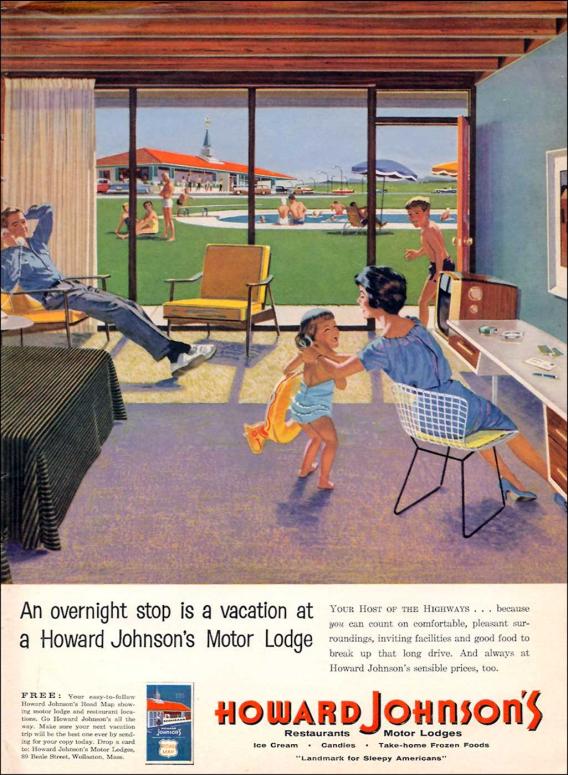

My father’s Polaroid cameras now gather dust in a dark closet. Like the orange-roofed Howard Johnson’s restaurants and “motor lodges” to which my family repaired each time we went on vacation, they are relics of the happy childhood for which I will forever be grateful. But just as Howard Johnson’s shuttered its remaining restaurants years ago, so did Polaroid stop making film in 2008, in the process turning my father’s once-treasured cameras into handsome pieces of junk, relegated to irrelevance, like the Polaroid Corporation itself, by the coming of digital photography.

My father’s Polaroid cameras now gather dust in a dark closet. Like the orange-roofed Howard Johnson’s restaurants and “motor lodges” to which my family repaired each time we went on vacation, they are relics of the happy childhood for which I will forever be grateful. But just as Howard Johnson’s shuttered its remaining restaurants years ago, so did Polaroid stop making film in 2008, in the process turning my father’s once-treasured cameras into handsome pieces of junk, relegated to irrelevance, like the Polaroid Corporation itself, by the coming of digital photography.

As for my Swinger, I’ve no idea what happened to it, but I still remember the jingle that Polaroid used to sell it back in 1965: It’s more than a camera/It’s almost alive/It’s only nineteen dollars and ninety-five. That’s $140.34 in today’s dollars, pretty serious money for a Christmas present in Smalltown, U.S.A. It’s sad to think that such a costly gift should have gone the way of all insufficiently loved toys. I wish my father were still around for me to tell him how much it meant to me once upon a time.

TT: Just because

SX-70, a promotional film made for Polaroid in 1972 by Charles and Ray Eames. The score is by Elmer Bernstein:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“My whole life has been spent trying to teach people that intense concentration for hour after hour can bring out in people resources they didn’t know they had.”

Edwin H. Land (quoted in Christopher Bonanos, Instant: The Story of Polaroid)

TT: Sometimes Macy’s does tell Gimbels!

The New York Times recently interviewed me about Satchmo at the Waldorf. Here’s part of the story, which will appear in print on Sunday:

Who knew Louis Armstrong had such a mouth on him? And we don’t mean embouchure.

With “Satchmo at the Waldorf,” which opened Oct. 3 at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven (after an earlier run in Lenox, Mass.), the critic Terry Teachout becomes a playwright. And as such, he seems to have a lot in common with David Mamet. That is, his dialogue flows with four-letter words like Beaujolais at a French cafe. The primary offender and main character is Armstrong himself, jazz trumpeter, singer and postwar America’s first nonwhite sweetheart….

Armstrong’s duality fascinates Mr. Teachout, a jazz aficionado who was born in Missouri and lived in Kansas City in his 20s. “The public Armstrong and the private Armstrong are very different,” he said. But, he emphasized, “they’re both true.”

“When he went out onstage and smiled that big smile and sang ‘Dolly,’ he wasn’t lying,” he continued. “He was a fundamentally largehearted man. But he was also a genius and also a complicated man….”

Read the whole thing here.