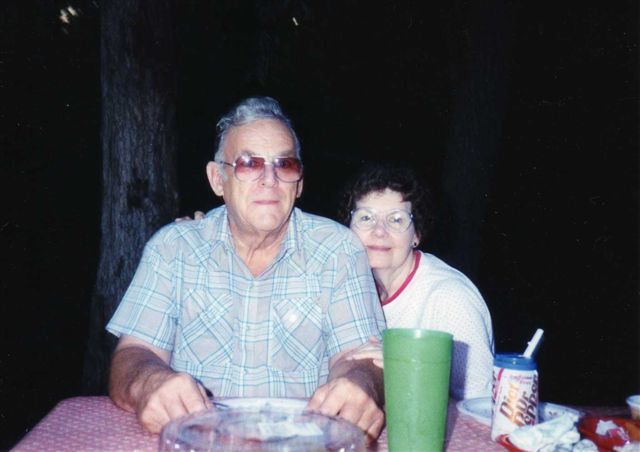

My brother, who became the unofficial Teachout family archivist by virtue of the fact that he lived so close to (and is now moving into) the house where we grew up, just sent me an e-mail containing snapshots of my mother and father. Some of them I remember vividly, while others were unfamiliar to me. All of them moved me, some to tears.

In recent weeks I’ve been thinking about my parents with increasing frequency, no doubt because the success of Satchmo at the Waldorf makes me wish that they’d lived to see it–though I wouldn’t have wanted to try to explain to my mother why I’d put such spectacularly obscene language in the mouth of her beloved Louis Armstrong! Be that as it may, it’s nice to be able to get a look at them again, and I thought it might possibly amuse you to see two of my favorite photos:

• I took this one shortly after my parents came to New York for their first and only joint visit in 1983 or 1984. It documents my mother’s first subway ride. If memory serves, we were headed down to Rockefeller Center. Even at its best, the New York subway system can be a formidable obstacle course for anyone who’s spent the whole of his life in a series of small Midwestern towns, and I have crystal-clear memories of the morning that I escorted my mother down the steps and into the maelstrom.

• I took this one shortly after my parents came to New York for their first and only joint visit in 1983 or 1984. It documents my mother’s first subway ride. If memory serves, we were headed down to Rockefeller Center. Even at its best, the New York subway system can be a formidable obstacle course for anyone who’s spent the whole of his life in a series of small Midwestern towns, and I have crystal-clear memories of the morning that I escorted my mother down the steps and into the maelstrom.

Though she was palpably nervous, she was also a plucky woman who rarely let anything faze her, and this tight-lipped portrait of a middle-aged woman determined not to display her anxiety has never failed to put a smile on my own face.

•  My father, like so many men of his generation, loved to go “camping,” by which he meant staying somewhere other than home in something other than a motel room. First he bought a tent, then a trailer, then a mobile home on Kentucky Lake, then–dream of dreams–a full-fledged motor home, and each summer he did his level best to get out of town as often as possible.

My father, like so many men of his generation, loved to go “camping,” by which he meant staying somewhere other than home in something other than a motel room. First he bought a tent, then a trailer, then a mobile home on Kentucky Lake, then–dream of dreams–a full-fledged motor home, and each summer he did his level best to get out of town as often as possible.

Needless to say, it was always taken for granted that my mother would come along, since he was incapable of functioning without her. (It would have been unimaginably awful had she predeceased him.) Alas, she hated the camping trips that made him so happy, but she was a loyal and devoted spouse, and on occasion she somehow contrived to enjoy herself. This picture was taken on one of those happy occasions.

Oh, how I miss them both.

Archives for 2012

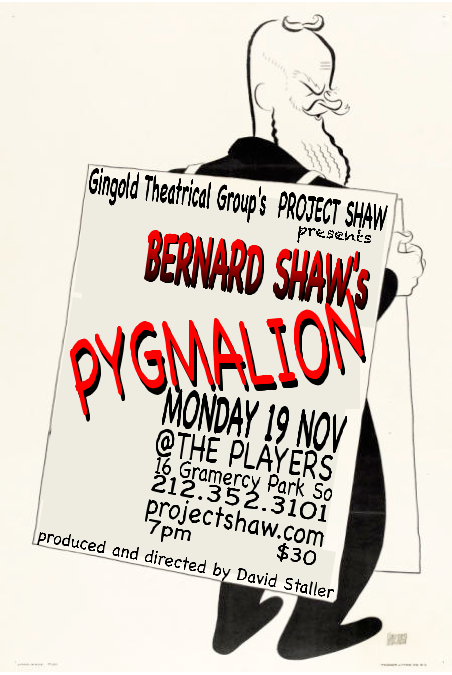

TT: A Shavian romp

I was the guest host last night for Project Shaw‘s concert-style reading of Pygmalion at the Players Club. Since critics are officially “not present” at Project Shaw productions, I speak purely as a civilian when I say that it was one of the most enjoyable presentations of a play by George Bernard Shaw that I’ve ever seen. David Staller’s bone-simple staging was deft and quick, and the actors played their parts with tremendous gusto. I regret to confess that this is my first evening with Project Shaw, but it definitely won’t be my last.

Next up: Saint Joan, on December 17. Don’t miss it.

If you’re curious, here’s what I had to say. Regular readers of this blog may notice that I lifted part of my introductory remarks from a recent Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column. Nobody noticed, so don’t tell!

* * *

It’s a pleasure to be here, and to talk about Shaw, an artist whom I admire greatly in spite of the fact that we have, so far as I know, only one thing in common. Like him, I’m now a critic and a playwright. Now that I’ve worked both sides of the proscenium, I know better than ever before that there are many things about the theater that can’t be learned from an aisle seat! I think I’m a better critic for having written a play and two opera libretti, and I dare say that Shaw might well have become a better playwright for having spent time as a working critic. At any rate, he certainly knew how seriously to take his reviews!

But enough about me–a sentence that Shaw, so far as I know, never spoke in his life. Let’s talk about Pygmalion for a moment. Nowadays most theatergoers know Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins from My Fair Lady, in which Lerner and Loewe sprinkled sugar all over Shaw’s greatest comedy. The real Pygmalion, by contrast, is a double-edged satire of the British class system that takes no less cutting a view of the progressive reformers who, like Shaw himself, sought and seek to flatten it out. He shows us that Professor Higgins, like so many of his well-meaning kind, prefers people in the mass to individual human beings. He treats Eliza like a lab rat, not a creature of flesh and blood, and her scornful dismissal of his high-minded heartlessness rings as true today as it did in 1913.

But enough about me–a sentence that Shaw, so far as I know, never spoke in his life. Let’s talk about Pygmalion for a moment. Nowadays most theatergoers know Eliza Doolittle and Henry Higgins from My Fair Lady, in which Lerner and Loewe sprinkled sugar all over Shaw’s greatest comedy. The real Pygmalion, by contrast, is a double-edged satire of the British class system that takes no less cutting a view of the progressive reformers who, like Shaw himself, sought and seek to flatten it out. He shows us that Professor Higgins, like so many of his well-meaning kind, prefers people in the mass to individual human beings. He treats Eliza like a lab rat, not a creature of flesh and blood, and her scornful dismissal of his high-minded heartlessness rings as true today as it did in 1913.

I think that much of Shaw’s effectiveness as a dramatist of ideas inhered in his absolute willingness to give the devil his due, and I think that Pygmalion might just be the best example of that willingness. But Shaw was no less alive to the contradictions in his own nature than to those in his characters, most of whom are mirrors in which bits and pieces of their creator are vividly reflected. Instead of making love, they talk rings around it–even the ones who long most for intimacy. They believe in rationality, but embrace the apocalypse of total war with a pathetic blend of ecstasy and relief, just like Shaw, who opposed British involvement in World War I but was himself a power-worshipper with a totalitarian itch who believed passionately in human perfectibility. And though they joke and joke and joke, they’re always kidding on the square, telling their brutal truths with such impish charm that you scarcely feel the knife slipping in until the blood starts to flow.

That is Shaw in a nutshell. He is a serious comedian, an artist who knows that in most human lives, absurdity and sorrow are woven together too tightly to be teased apart–and that it is comedy, not tragedy, which illustrates that fact most fully. Life is too complex to be painted solely in shades of black. Even as Shakespeare made room in Lear for the Fool, so does Shaw make room in his theatrical sermons for the pungent humor that, as Henry James so truly said, is the saving salt. So tonight, let us laugh with him…and at ourselves.

* * *

George Bernard Shaw on capital punishment:

TT: Lookback

From 2003:

From 2003:

I’ve lived in New York for the better part of two decades now, and you’d think I’d have gotten used to it. In a way, I suppose I have, but even now all it takes is a whiff of the unexpected and I catch myself boggling at that which the native New Yorker really does take for granted. As for my visits to Smalltown, U.S.A., they invariably leave me feeling like yesterday’s immigrant, marveling at things no small-town boy can ever really dismiss as commonplace, no matter how long he lives in the capital of the world….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Always they had been anti-Semite, always the sinews of any absolutism.”

William Haggard, Venetian Blind

TT: Read all about it

The Wilma Theater transfer of Satchmo at the Waldorf just got a rave review from Toby Zinman of the Philadelphia Inquirer:

It takes a brave theater critic to write a play, and a brave critic to review it–especially since Satchmo at the Waldorf is by Terry Teachout, the esteemed critic of the Wall Street Journal. So it’s both a pleasure and a relief to tell you it’s a great show….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: This moment, this minute

When you’re young, you take for granted that life is conjectural and its possibilities unlimited. Once you reach middle age, you know better. Each time I look up from the screen of the laptop on my desk, I look at a framed photograph of my parents, thinking for the umpteenth time that I’ll never see either one of them again. For them, the book of life is closed.

For me, on the other hand, the book is still open, and apparently remains full of surprises. Here’s something that I wrote on my fiftieth birthday:

For me, on the other hand, the book is still open, and apparently remains full of surprises. Here’s something that I wrote on my fiftieth birthday:

Like many people, my life has been a series of goals, a things-to-do list, and at fifty I now find myself in the position, at once pleasing and disconcerting, of having accomplished most of them. As for the things I haven’t yet done, nearly all of them are things I’m no longer likely to do, assuming I ever was: I doubt, for instance, that I’ll learn a second language or write a novel or become a father. I could spend the rest of my life running in place, and I suppose that would be perfectly fine. Except that I know it wouldn’t. The time will come, if it hasn’t already, when I’ll want to try my hand at something new–and I haven’t the slightest idea what it might be.

Now I know: I wrote a play and two opera libretti, all of which have since been professionally produced. In 2006 I had no idea that a part-time career as a dramatist lay dead ahead of me. It wasn’t something I’d ever imagined, much less sought, and no day passes on which I fail to be amazed by the fact that it happened. Presumably I’ll get used to this strange new reality sooner or later, but not yet.

Being a writer, I feel instinctively that I ought to have something staggeringly pithy and wise to say about all this. Alas, I have nothing to offer but the usual fill-in-the-blank clichés, which are no more interesting for being true. You are, of course, at liberty to feel hopeful or inspired by my experience, but the older I get, the less sure I am that anybody’s experience, least of all mine, is relevant to the rest of the world, or that life itself has some intelligible “meaning” that is capable of being communicated to others.

H.L. Mencken, who was the blackest of skeptics, offered this dire perspective on the meaning of life in a 1920 essay:

(1) The cosmos is a gigantic fly-wheel making 10,000 revolutions a minute.

(2) Man is a sick fly taking a dizzy ride on it.

(3) Religion is the theory that the wheel was designed and set spinning to give him the ride.

I think that Mencken, as he so often did, was coming it more than a little bit high. Justice Holmes, on the other hand, said something similar but truer around the same time in a letter to an old friend: “I was repining at the thought of my slow progress–how few new ideas I had or picked up–when it occurred to me to think of the total of life and how the greater part was wholly absorbed in living and continuing life–victuals–procreation–rest and eternal terror. And I bid myself accept the common lot; an adequate vitality would say daily, ‘God, what a good sleep I’ve had,’ ‘My eye, that was dinner,’ ‘Now for a fine rattling walk’–in short, life as an end in itself.” Those are wise words.

I became friends this past summer with a pair of installation artists, both of whom freely accept and embrace the ephemerality of their creations. I admire them for it, since this is something I find all but impossible to do. Most people who write books, after all, do so in the (usually) foolish hope that their work will outlast them. I regret to say that I’m no different, though at least I’m realistic about my prospects for posthumous survival, which I take to be nugatory.

So why do I write, other than for money? The answer is surprisingly simple: I do it because making art is one of the best ways that I know to make the present moment an end in itself. “Why are you stingy with yourselves?” George Balanchine used to ask his dancers. “Why are you holding back? What are you saving for–for another time? There are no other times. There is only now. Right now.”

So why do I write, other than for money? The answer is surprisingly simple: I do it because making art is one of the best ways that I know to make the present moment an end in itself. “Why are you stingy with yourselves?” George Balanchine used to ask his dancers. “Why are you holding back? What are you saving for–for another time? There are no other times. There is only now. Right now.”

I thought of those words on Saturday as I watched Satchmo at the Waldorf at Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater. John Douglas Thompson had the opening-night crowd in the palm of his hand, and the applause at show’s end was tumultuous. All of us–myself very much included–were completely present in the moment. Nothing else mattered, or even existed.

It happens that I included Mr. B’s words, as well as the preceding quotation by Justice Holmes, in a 2005 posting on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the day that I moved to New York City. Here’s what I said at the end of those fugitive reflections, which are not unlike these fugitive reflections: “Like the cops say, Rule No. 1 is to go home alive at the end of your shift. Every day is a victory over the abyss.”

It is, I gather, a privilege of middle age to repeat oneself, and I hope it’s not an abuse of the privilege to do so at a seven-year interval. So for those of you just joining us, allow me to sum up what I think the creation of Satchmo at the Waldorf, The Letter, and Danse Russe has taught me, which is that surprising things can happen to a person who marches into the nearest crossroads, takes a deep breath, and moves decisively in one direction or another. It may not even matter which path you choose. The only mistake you can make is to stand still. Yes, the possibilities of life are strictly and cruelly limited, but to move forward, to grasp the larger hope, is to defeat the abyss, if only for another day. There is only now.

* * *

Robert Johnson sings “Cross Road Blues”:

TT: Guest shot

Project Shaw, the estimable New York outfit that presents monthly Monday-night concert readings of the plays of George Bernard Shaw, has now gotten around to Pygmalion, the famous 1912 play on which My Fair Lady is based. The production is directed by David Staller, who knows more about Shaw than just about anybody. The performance will be narrated by Michael Musto, and I’m the guest host, in which capacity I’ll be saying a few concise introductory words about Shaw and the play.

Project Shaw, the estimable New York outfit that presents monthly Monday-night concert readings of the plays of George Bernard Shaw, has now gotten around to Pygmalion, the famous 1912 play on which My Fair Lady is based. The production is directed by David Staller, who knows more about Shaw than just about anybody. The performance will be narrated by Michael Musto, and I’m the guest host, in which capacity I’ll be saying a few concise introductory words about Shaw and the play.

The performance will take place at the Players Club, 19 Gramercy Park South, at seven p.m. For tickets or more information, go here.

TT: Just because

Paul Taylor’s Esplanade, set to the music of Johann Sebastian Bach and performed by the Paul Taylor Dance Company, originally telecast on PBS’ Dance in America in 1978:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)