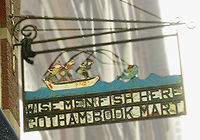

I’ve lived in New York for more than a quarter of a century, long enough to feel nostalgic whenever I see movies that were made around the time that I moved here. One such film is Crossing Delancey, released in 1988, in which Amy Irving plays a young woman who works at a prestigious independent bookstore that appears to have been modeled after the Gotham Book Mart.

I’ve lived in New York for more than a quarter of a century, long enough to feel nostalgic whenever I see movies that were made around the time that I moved here. One such film is Crossing Delancey, released in 1988, in which Amy Irving plays a young woman who works at a prestigious independent bookstore that appears to have been modeled after the Gotham Book Mart.

As Crossing Delancey opens, New Day Books is throwing a party to celebrate its having escaped the wrecking ball. Those were the days when high-end indie bookstores were hip and ostensibly serious writers could still aspire to a certain measure of pop-culture réclame. Sic transit! The real-life Gotham Book Mart sold off its stock and closed its doors forever in 2007, just before the brick-and-mortar bookselling business imploded. As for Irving, who was (I admit it) my cinematic dream girl in 1988, she’s now fifty-nine, three years my senior, and stupendously wealthy. She no longer makes movies, but I’ve reviewed three of her stage appearances in my Wall Street Journal drama column, all of them favorably. The last time I saw her in the flesh, I was in the company of a twenty-five-year-old friend who didn’t know her name.

I still enjoy watching Irving in her radiant youth, and I also enjoy watching Peter Riegert, a low-key, impeccably solid actor who never quite managed to become a star but did appear in two other fondly remembered films, Animal House and Local Hero. It’s also fun to get a brief but already characteristic glimpse of David Hyde Pierce, who was twenty-nine and unknown when Crossing Delancey was released.

I still enjoy watching Irving in her radiant youth, and I also enjoy watching Peter Riegert, a low-key, impeccably solid actor who never quite managed to become a star but did appear in two other fondly remembered films, Animal House and Local Hero. It’s also fun to get a brief but already characteristic glimpse of David Hyde Pierce, who was twenty-nine and unknown when Crossing Delancey was released.

What I like best about Crossing Delancey, though, is that it reminds me of the fact that I knew next to nothing about Jews when I first saw it. The Jewishness of the characters played by Irving and Riegert in Crossing Delancey is, of course, the film’s central theme, and it was by watching their uptown-downtown courtship (he owns a pickle store on the Lower East Side) that I first got wind, if only in greatly watered-down form, of some of the class-driven complexities of contemporary Jewish life.

To be sure, I’d read such now-forgotten books as Sam Levenson’s Everything but Money and Allan Sherman’s A Gift of Laughter, for warm, cuddly Jewish humorists were all the rage when I was a boy. Indeed, I must have read Everything but Money a dozen times, trying to imagine what it would have felt like to grow up in a large family, the way that Sam Levenson and my mother had. That their experiences were in some fundamental way dissimilar never occurred to me. So far as I knew, all large families were alike. I understood that Levenson was the son of Jewish immigrants, and that their religious beliefs were different from mine, but the rest, I assumed, was merely local color.

Nor was I well equipped to ferret out any additional differences. I had no idea, for instance, that most of the comedians I saw on television in the Sixties were Jewish, and even if I had, it probably wouldn’t have mattered, the process of assimilation having by then gone a long way toward denaturing mass-market Jewish comedy. What would it have meant to me to learn that Jack Benny was Jewish? Or Alan King? I knew nothing of the briny, uncompromising tang of full-bore Jewish culture, any more than I knew what a real pickle tasted like from having eaten the bland factory-made ones sold in jars at the local supermarket.

Only rarely did a whiff of something excitingly alien find its way to the TV set in the family room of my Missouri home. I remember being puzzled by Jackie Mason’s accent when I saw him on The Ed Sullivan Show, and puzzled in a different way by Woody Allen’s references to being Jewish, but my puzzlement was no more than that. I didn’t yet know that it was merely the tip of a cultural iceberg that I would spend a good deal of my adult life exploring, or that I would soon feel entirely at home in the once-strange world that I saw depicted in Crossing Delancey. If you’d told me in 1988 that I’d eventually become Commentary‘s most frequent contributor–I’ve had a piece in virtually every issue since 1995–I would have laughed in your face.

Only rarely did a whiff of something excitingly alien find its way to the TV set in the family room of my Missouri home. I remember being puzzled by Jackie Mason’s accent when I saw him on The Ed Sullivan Show, and puzzled in a different way by Woody Allen’s references to being Jewish, but my puzzlement was no more than that. I didn’t yet know that it was merely the tip of a cultural iceberg that I would spend a good deal of my adult life exploring, or that I would soon feel entirely at home in the once-strange world that I saw depicted in Crossing Delancey. If you’d told me in 1988 that I’d eventually become Commentary‘s most frequent contributor–I’ve had a piece in virtually every issue since 1995–I would have laughed in your face.

New York is the greatest school in the world, a place that introduces you to things of whose existence you’d never dreamed. It can also change you beyond recognition–if you let it. I didn’t. I never, ever wanted to be an ersatz New Yorker. All I wanted was to widen my horizons, to understand (among countless other things) what Isaac Bashevis Singer could possibly have meant when he remarked in the preface to Enemies, a Love Story that “I did not have the privilege of going through the Hitler holocaust.” Now, up to a point, I think I do.

* * *

An interview with Sam Levenson, originally telecast in 1974 on CUNY-TV’s Day at Night:

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog