“Perhaps a creature of so much ingenuity and deep memory is almost bound to grow alienated from his world, his fellows, and the objects around him. He suffers from a nostalgia for which there is no remedy upon earth except as it is to be found in the enlightenment of the spirit–some ability to have a perceptive rather than an exploitive relationship with his fellow creatures.”

Loren Eiseley, The Invisible Pyramid

Archives for December 2012

PLAY

Our Town (Huntington Theatre Company, Calderwood Pavilion, 527 Tremont St., Boston, extended through Jan. 26). David Cromer’s staging of Thornton Wilder’s masterpiece, which ran off Broadway for more than 600 performance, is now being remounted in Boston. It’s the greatest revival of a classic play that I’ve seen in my entire theatergoing life, a re-creative landmark that at once arrestingly original and fundamentally faithful in its approach to the author’s well-loved text. Don’t listen if anybody tries to tell you about the surprise ending–and once you’ve seen the show, don’t tell anybody what happens (TT).

CD

Donald Fagen, Sunken Condos (Reprise). A new solo album from the co-founder of Steely Dan, Sunken Condos is very much in the now-familiar vein of Morph the Cat, its immediate predecessor. That is, however, a compliment, not a knock. Sly lyrics, subtle harmonies, richly textured rock/jazz/R&B instrumental tracks, virtuoso playing from all parties concerned–what more could you possibly want? This is rock for grownups, wholly adult in its musical language and emotional concerns (TT).

TT: Fill the air

Six years ago I posted a list of my favorite Christmas records. I still like all of them, and so, I hope, will you.

TT: Lookback

From 2005:

From 2005:

I recently saw a stage actress I know in an episode of a popular TV series. This was a new experience for me. I’ve watched any number of writer friends hold forth on talk shows, and I’ve even tuned into David Letterman to see a band whose members I know quite well. But all those people were being themselves, more or less, whereas my actress friend was pretending to be someone else. Of course she was in one sense wholly herself (I knew her smile in an instant/I knew the curve of her face), and the part she played drew deeply on her familiar energy. Nor was she made up in any deceptive way: she looked like the person I know. Yet some uncanny transformation had nonetheless taken place, and I found myself to be more than a little bit disoriented as I watched her on the screen….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“When I watched you dancing that day, I saw something else. I saw a new world coming rapidly. More scientific, efficient, yes. More cures for the old sicknesses. Very good. But a harsh, cruel world. And I saw a little girl, her eyes tightly closed, holding to her breast the old kind world, one that she knew in her heart could not remain, and she was holding it and pleading, never to let her go. That is what I saw. It wasn’t really you, what you were doing, I know that. But I saw you and it broke my heart. And I’ve never forgotten.”

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

TT: We’ll see

Satchmo at the Waldorf wrapped up its third successive (and successful) run on Sunday afternoon at Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater. I wish I had something brilliantly appropriate to say, but I don’t. I’m simply grateful to my wonderful collaborators, John Douglas Thompson and Gordon Edelstein foremost among them, and to the three theater companies that dared to take a chance on a first-time playwright.

What comes next? I wish I could tell you, but things are still very much up in the air as of this moment. What I can say is that the success of Satchmo to date has already outstripped my wildest dreams. No matter what may lie ahead, I’m proud and satisfied beyond measure.

To all who came to see Satchmo in Lenox, New Haven, or Philadelphia, my heartfelt thanks for helping to make it the experience of a lifetime. I hope you enjoyed it half as much as I did!

TT: Assimilated

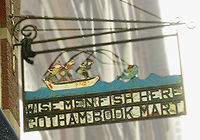

I’ve lived in New York for more than a quarter of a century, long enough to feel nostalgic whenever I see movies that were made around the time that I moved here. One such film is Crossing Delancey, released in 1988, in which Amy Irving plays a young woman who works at a prestigious independent bookstore that appears to have been modeled after the Gotham Book Mart.

I’ve lived in New York for more than a quarter of a century, long enough to feel nostalgic whenever I see movies that were made around the time that I moved here. One such film is Crossing Delancey, released in 1988, in which Amy Irving plays a young woman who works at a prestigious independent bookstore that appears to have been modeled after the Gotham Book Mart.

As Crossing Delancey opens, New Day Books is throwing a party to celebrate its having escaped the wrecking ball. Those were the days when high-end indie bookstores were hip and ostensibly serious writers could still aspire to a certain measure of pop-culture réclame. Sic transit! The real-life Gotham Book Mart sold off its stock and closed its doors forever in 2007, just before the brick-and-mortar bookselling business imploded. As for Irving, who was (I admit it) my cinematic dream girl in 1988, she’s now fifty-nine, three years my senior, and stupendously wealthy. She no longer makes movies, but I’ve reviewed three of her stage appearances in my Wall Street Journal drama column, all of them favorably. The last time I saw her in the flesh, I was in the company of a twenty-five-year-old friend who didn’t know her name.

I still enjoy watching Irving in her radiant youth, and I also enjoy watching Peter Riegert, a low-key, impeccably solid actor who never quite managed to become a star but did appear in two other fondly remembered films, Animal House and Local Hero. It’s also fun to get a brief but already characteristic glimpse of David Hyde Pierce, who was twenty-nine and unknown when Crossing Delancey was released.

I still enjoy watching Irving in her radiant youth, and I also enjoy watching Peter Riegert, a low-key, impeccably solid actor who never quite managed to become a star but did appear in two other fondly remembered films, Animal House and Local Hero. It’s also fun to get a brief but already characteristic glimpse of David Hyde Pierce, who was twenty-nine and unknown when Crossing Delancey was released.

What I like best about Crossing Delancey, though, is that it reminds me of the fact that I knew next to nothing about Jews when I first saw it. The Jewishness of the characters played by Irving and Riegert in Crossing Delancey is, of course, the film’s central theme, and it was by watching their uptown-downtown courtship (he owns a pickle store on the Lower East Side) that I first got wind, if only in greatly watered-down form, of some of the class-driven complexities of contemporary Jewish life.

To be sure, I’d read such now-forgotten books as Sam Levenson’s Everything but Money and Allan Sherman’s A Gift of Laughter, for warm, cuddly Jewish humorists were all the rage when I was a boy. Indeed, I must have read Everything but Money a dozen times, trying to imagine what it would have felt like to grow up in a large family, the way that Sam Levenson and my mother had. That their experiences were in some fundamental way dissimilar never occurred to me. So far as I knew, all large families were alike. I understood that Levenson was the son of Jewish immigrants, and that their religious beliefs were different from mine, but the rest, I assumed, was merely local color.

Nor was I well equipped to ferret out any additional differences. I had no idea, for instance, that most of the comedians I saw on television in the Sixties were Jewish, and even if I had, it probably wouldn’t have mattered, the process of assimilation having by then gone a long way toward denaturing mass-market Jewish comedy. What would it have meant to me to learn that Jack Benny was Jewish? Or Alan King? I knew nothing of the briny, uncompromising tang of full-bore Jewish culture, any more than I knew what a real pickle tasted like from having eaten the bland factory-made ones sold in jars at the local supermarket.

Only rarely did a whiff of something excitingly alien find its way to the TV set in the family room of my Missouri home. I remember being puzzled by Jackie Mason’s accent when I saw him on The Ed Sullivan Show, and puzzled in a different way by Woody Allen’s references to being Jewish, but my puzzlement was no more than that. I didn’t yet know that it was merely the tip of a cultural iceberg that I would spend a good deal of my adult life exploring, or that I would soon feel entirely at home in the once-strange world that I saw depicted in Crossing Delancey. If you’d told me in 1988 that I’d eventually become Commentary‘s most frequent contributor–I’ve had a piece in virtually every issue since 1995–I would have laughed in your face.

Only rarely did a whiff of something excitingly alien find its way to the TV set in the family room of my Missouri home. I remember being puzzled by Jackie Mason’s accent when I saw him on The Ed Sullivan Show, and puzzled in a different way by Woody Allen’s references to being Jewish, but my puzzlement was no more than that. I didn’t yet know that it was merely the tip of a cultural iceberg that I would spend a good deal of my adult life exploring, or that I would soon feel entirely at home in the once-strange world that I saw depicted in Crossing Delancey. If you’d told me in 1988 that I’d eventually become Commentary‘s most frequent contributor–I’ve had a piece in virtually every issue since 1995–I would have laughed in your face.

New York is the greatest school in the world, a place that introduces you to things of whose existence you’d never dreamed. It can also change you beyond recognition–if you let it. I didn’t. I never, ever wanted to be an ersatz New Yorker. All I wanted was to widen my horizons, to understand (among countless other things) what Isaac Bashevis Singer could possibly have meant when he remarked in the preface to Enemies, a Love Story that “I did not have the privilege of going through the Hitler holocaust.” Now, up to a point, I think I do.

* * *

An interview with Sam Levenson, originally telecast in 1974 on CUNY-TV’s Day at Night: