As I mentioned the other day, I won’t be making my customary Christmas trip to Smalltown, U.S.A., this year. I can’t remember the last time I spent Christmas anywhere else, but now that my mother is dead, I suspect that it may be quite some time before I return once more to the place where I come from.

As I mentioned the other day, I won’t be making my customary Christmas trip to Smalltown, U.S.A., this year. I can’t remember the last time I spent Christmas anywhere else, but now that my mother is dead, I suspect that it may be quite some time before I return once more to the place where I come from.

Such being the case, I find myself inclined of late to prop up my memories of Smalltown with the crutch of fictional representation. Alas, that’s easier said than done. “Every great man nowadays has his disciples, and it is usually Judas who writes the biography,” said Oscar Wilde. I’ve noticed something similar when it comes to fictional treatments of small-town life in America, most of which are the work of bright, embittered émigrés who couldn’t wait to grow up, move to the big city, and write novels, most of them bad, about how much they hated their childhoods.

I, on the other hand, grew up, moved to the big city, and wrote an affectionate memoir that is mostly about Smalltown, U.S.A., a place that I loved greatly yet still chose to leave, not because I hated my childhood but because I knew that (as I made Louis Armstrong say in Satchmo at the Waldorf) you’ve got to do what you’re made to do. I was made to do things that I couldn’t do in a small town, so I went elsewhere to do them. Yet I never stopped loving Smalltown, and it is because of that love, clear-eyed yet enduring, that I find it hard to see the world I knew in the books I read. Only two of them, James Gould Cozzens’ The Just and the Unjust and John P. Marquand’s Point of No Return, suggest with anything like sympathetic accuracy the real-life town where I grew up.

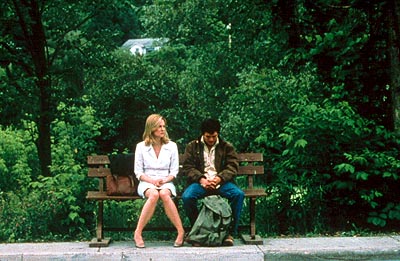

For the most part, you have to look to films, not novels, to get a clear sense of small-town life, and it’s surprising–or maybe not–how few of the ostensibly serious ones hit the mark at all squarely. By far the most convincing cinematic portrayal of a small town that I know is Kenneth Lonergan’s You Can Count on Me, a modest little masterpiece that gets absolutely everything right. Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show comes close, but it’s too harsh to be entirely persuasive, at least to me.

For the most part, you have to look to films, not novels, to get a clear sense of small-town life, and it’s surprising–or maybe not–how few of the ostensibly serious ones hit the mark at all squarely. By far the most convincing cinematic portrayal of a small town that I know is Kenneth Lonergan’s You Can Count on Me, a modest little masterpiece that gets absolutely everything right. Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show comes close, but it’s too harsh to be entirely persuasive, at least to me.

When you turn from high art to commercial fantasy, on the other hand, you sometimes find, paradoxical as it may sound, rather more truth. A case in point is Doc Hollywood, David Caton-Jones’ 1991 romcom about an arrogant young surgeon (Michael J. Fox) who is forced by cinematic circumstances to spend a week in Grady, a quirkily idyllic rural community somewhere or other below the Mason-Dixon line, where he meets a sly but vulnerable single mother (Julie Warner) whose charms inspire him to settle down in a place that he dismissed at first as “heehaw hell.”

Needless to say, Doc Hollywood is no masterpiece, just as Grady and its eccentric residents are far more than a little bit too good to be true–but then, they’re not supposed to be true. As Caton-Jones explained in an interview:

[Frank] Capra used to make movies about small towns all the time, and I loved them. You don’t realize how seductive American movies are for the rest of the world–and for me, growing up in a little place in Scotland. The movie reflects the way I grew up thinking about America….There are myths that touch internal chords that we don’t really understand. If an American had filmed this, I think it would probably have been a lot more skeptical.

That’s why Doc Hollywood works, both as entertainment and as truth. Beneath its amiably zany whimsy, it comes closer than any other popular movie I know to embodying the myth of American community. Grady, it seems, is a place whose citizens know, care about, and look after one another, where eccentricity is not merely tolerated but cherished and the absence of big-city distractions makes it possible to pay closer attention to the things that matter most.

“You don’t see a lot of things in Grady, but what you do see, you see a lot of,” says Lou, the character played by Julie Warner in Doc Hollywood. She doesn’t mean it as a compliment to her home town, about whose cultural limitations she has no illusions, having lived briefly in New York City. At the same time, though, Lou also knows that there’s more to life than skyscrapers and concert halls, and so she has consciously chosen to return to Grady and spend the rest of her own life among her own people, even if it deprives her of the man who may be her true love.

“You don’t see a lot of things in Grady, but what you do see, you see a lot of,” says Lou, the character played by Julie Warner in Doc Hollywood. She doesn’t mean it as a compliment to her home town, about whose cultural limitations she has no illusions, having lived briefly in New York City. At the same time, though, Lou also knows that there’s more to life than skyscrapers and concert halls, and so she has consciously chosen to return to Grady and spend the rest of her own life among her own people, even if it deprives her of the man who may be her true love.

I wrote in September about paying a visit to Spring Green, a tiny Wisconsin town of which I’ve long been fond:

Something about Spring Green speaks powerfully to me, so much so that my heart lifts each summer when I drive past the city-limits sign. The scale is right, the people agreeable, and there’s even a first-class bookstore. If my life were somehow to arrange itself differently–very differently, to be sure–I could see myself living there.

Whenever I find myself in small towns like Spring Green, I remember how it felt to grow up in Smalltown, U.S.A., where the “myth” of community is in fact a daily reality, one that strengthens and comforts all who participate in it. My mother could never have lived anywhere else, and my brother has never wanted to. I chose another path, one that I’ve never regretted taking–but you don’t have to doubt that you took the right path to know what you missed by taking it.

Whenever I find myself in small towns like Spring Green, I remember how it felt to grow up in Smalltown, U.S.A., where the “myth” of community is in fact a daily reality, one that strengthens and comforts all who participate in it. My mother could never have lived anywhere else, and my brother has never wanted to. I chose another path, one that I’ve never regretted taking–but you don’t have to doubt that you took the right path to know what you missed by taking it.

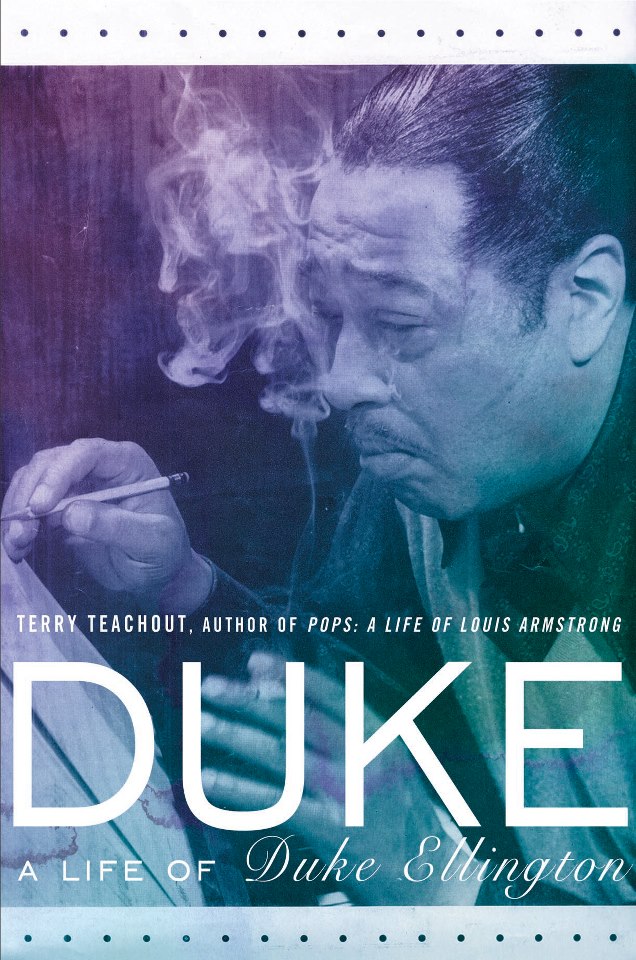

I recently spent a few days in Los Angeles with Steven Lasker, the world’s foremost collector of Ellingtonia, who probably knows more than anyone about Duke Ellington. (He definitely knows more than I do.) Not only did Steven allow me to browse freely in his amazing collection, but he made two priceless suggestions. He told me that Duke would be a better title for my biography than Mood Indigo, and he presented me with a little-known Ellington photograph that he thought would make an ideal cover image for the book.

I recently spent a few days in Los Angeles with Steven Lasker, the world’s foremost collector of Ellingtonia, who probably knows more than anyone about Duke Ellington. (He definitely knows more than I do.) Not only did Steven allow me to browse freely in his amazing collection, but he made two priceless suggestions. He told me that Duke would be a better title for my biography than Mood Indigo, and he presented me with a little-known Ellington photograph that he thought would make an ideal cover image for the book.