I spotted this sentence in a recent item about Satchmo at the Waldorf:

Terry Teachout, the playwright, is out to prove that critics–he’s the theater reviewer for The Wall Street Journal–can walk the walk, too.

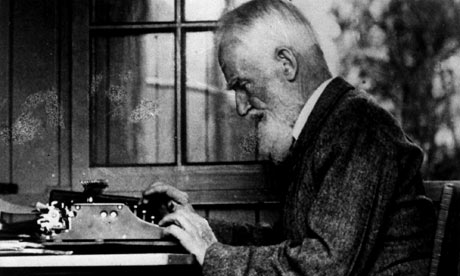

Well, no, I’m not. I definitely didn’t write Satchmo at the Waldorf to prove that critics are capable of writing plays. (George Bernard Shaw settled that one a long time ago.) Nor did I write it to prove that Louis Armstrong was a great artist, or that Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis were wrong to call him an Uncle Tom.

Well, no, I’m not. I definitely didn’t write Satchmo at the Waldorf to prove that critics are capable of writing plays. (George Bernard Shaw settled that one a long time ago.) Nor did I write it to prove that Louis Armstrong was a great artist, or that Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis were wrong to call him an Uncle Tom.

In fact, I didn’t write it to “prove” anything at all.

Here’s why I wrote Satchmo: (1) I thought it would be fun. (2) I also thought that trying to write a play would be an interesting and exciting challenge. And that’s about the size of it.

I’m not saying that Satchmo at the Waldorf is devoid of wider implications. Far from it. You can’t write a play about the life of a black jazz musician, least of all one as historically significant as Armstrong, without touching on the subject of race relations in America. What’s more, I upped the ante considerably when I decided that the same actor would play Armstrong and Joe Glaser, his Jewish manager. But I didn’t do so to make a non-theatrical point–I did it for dramatic effect. You can’t have a play without conflict, and the trick to making a one-man play dramatic is finding a way to make that conflict palpable, even visible. By making Glaser an onstage character in the play, I embodied the emotional conflict that lies at the heart of Satchmo.

Does my decision to have a black actor play a white man have political overtones? That’s for you to decide. But if you read me at all regularly, you know that I’m a skeptic when it comes to political art, most of which inclines to propagandizing at the expense of artfulness. A boring work of art can’t persuade anyone of anything, not even that we should believe what it tells us about the world. And nothing is more boring–or less believable–than a story with only one side.

It stands to reason that I wouldn’t want to create that kind of art. My interests lie elsewhere. Maurice Ravel affixed to his Valses nobles et sentimentales this epigraph by the French poet Henri de Régnier: The delicious and always new pleasure of a useless occupation. I love that phrase, and up to a point (though not beyond) it explains why I wrote Satchmo at the Waldorf. Fairfield Porter came even closer, though, when he wrote that his goal as a painter was “to express what Bonnard said Renoir told him: make everything more beautiful.” At bottom, that’s what I’ve tried to do with my first play. I’ve taken some of the known facts of Louis Armstrong’s life and some of what Armstrong himself said and wrote about his life and work, and shaped it into a work of art that happens to be about two real-life historical figures.

It stands to reason that I wouldn’t want to create that kind of art. My interests lie elsewhere. Maurice Ravel affixed to his Valses nobles et sentimentales this epigraph by the French poet Henri de Régnier: The delicious and always new pleasure of a useless occupation. I love that phrase, and up to a point (though not beyond) it explains why I wrote Satchmo at the Waldorf. Fairfield Porter came even closer, though, when he wrote that his goal as a painter was “to express what Bonnard said Renoir told him: make everything more beautiful.” At bottom, that’s what I’ve tried to do with my first play. I’ve taken some of the known facts of Louis Armstrong’s life and some of what Armstrong himself said and wrote about his life and work, and shaped it into a work of art that happens to be about two real-life historical figures.

W.H. Auden claimed in his poem In Memory of W.B. Yeats that “poetry makes nothing happen.” He was, of course, speaking as a poet, and so, in my far more modest way, am I. I know perfectly well that if you should go to see Satchmo at the Waldorf, you’ll come away knowing more about Louis Armstrong at evening’s end than you did when the curtain went up. But I didn’t write the play to teach you anything, much less to prove anything. I wrote it to give myself pleasure and–if possible–to make the world a little bit more beautiful.

* * *

Charles Munch leads the Boston Symphony in a 1963 performance of Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales: