My father owned three Polaroid cameras and bought a fourth one for me when I was a boy. I thought of them–and of him–when I read Christopher Bonanos’ Instant: The Story of Polaroid, a newly published book about Edwin H. Land, the inventor of the first “instant camera,” and the once-powerful, now-forgotten corporation that he created.

My father owned three Polaroid cameras and bought a fourth one for me when I was a boy. I thought of them–and of him–when I read Christopher Bonanos’ Instant: The Story of Polaroid, a newly published book about Edwin H. Land, the inventor of the first “instant camera,” and the once-powerful, now-forgotten corporation that he created.

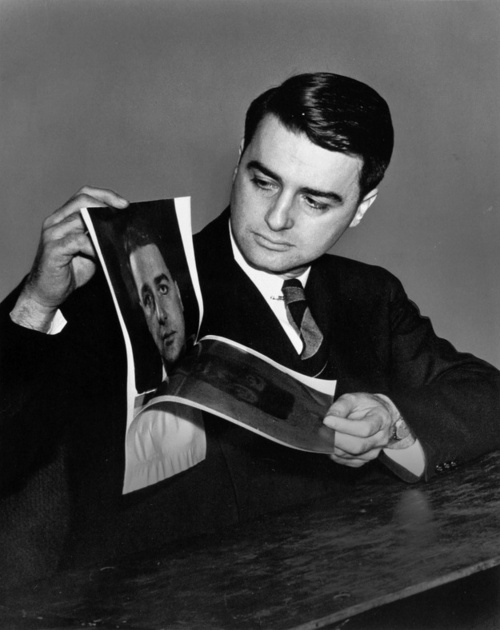

Today’s smartphone-addicted youngsters can’t begin to fathom the cultural impact of the Polaroid Model 95 camera, which took sepia-toned photographs that developed themselves in sixty seconds. When Land gave the first public demonstration of his invention in 1947, taking a picture of himself and displaying it to the audience a minute later, the audience gasped. What happened next, says Bonanos, was very nearly as astonishing:

The next morning, the shot of Land revealing his own mug got big play in the New York Times, along with an appreciative editorial. Newspapers all over the county ran the story. The following Monday, it was the “Picture of the Week” in Life magazine, then the alpha and omega of American photojournalism….

Remember that amateur photography, in 1947, had come along only a modest amount since [George] Eastman’s first film in 1888. Yes, the cameras were better and more versatile, and color was becoming widely available. When it came time to process your pictures, however, you had two choices: build yourself a darkroom, or get your film to a lab. If you didn’t live in a big city, you were probably mailing your film back to Kodak, same as in 1888. The leap to Polaroid was like replacing a messenger on horseback with your first telephone. “There is nothing like this in the history of photograph” was how the unsigned Times editorial put it.

It stands to reason that a natural-born geek like me would have been fascinated by the technological magic of Polaroid’s self-developing process, and so I was. Alas, I had no visual sense–it wasn’t until adulthood that I learned how to use my eyes in anything more than a superficial way–and I’ve never felt much inclined to preserve corporeal souvenirs of my past life, not even the carefully posed vacation snapshots that my father took by the truckload. The Polaroid Swinger, a low-priced model that came out in 1965, was the only camera that I’ve ever owned, or wanted to own.

It stands to reason that a natural-born geek like me would have been fascinated by the technological magic of Polaroid’s self-developing process, and so I was. Alas, I had no visual sense–it wasn’t until adulthood that I learned how to use my eyes in anything more than a superficial way–and I’ve never felt much inclined to preserve corporeal souvenirs of my past life, not even the carefully posed vacation snapshots that my father took by the truckload. The Polaroid Swinger, a low-priced model that came out in 1965, was the only camera that I’ve ever owned, or wanted to own.

No doubt part of its irresistible appeal to me lay in the youth-oriented TV commercials that introduced the Swinger (as well as a very young Ali MacGraw) to the American public:

That said, I also suspect that when I put the Swinger at the top of my Christmas list for 1966, what I really had in mind was to emulate my father, a deep-voiced, gadget-loving man’s man whom I admired without reserve but to whom I never succeeded in becoming close. The problem was that we had little in common save for a deep-seated belief in the virtue of professionalism. “A thing worth doing, son, is worth doing right,” he told me over and over again, not realizing that the two of us had radically different notions of what was worth doing.

When I was ten, though, I still believed that my father knew everything and could do anything, and it must have occurred to me, consciously or not, that it would please him if I tried to do something that he himself enjoyed. So I asked for and received a Swinger, and spent the next couple of years earnestly taking my own carefully posed vacation snapshots, none of which, so far as I know, have survived.

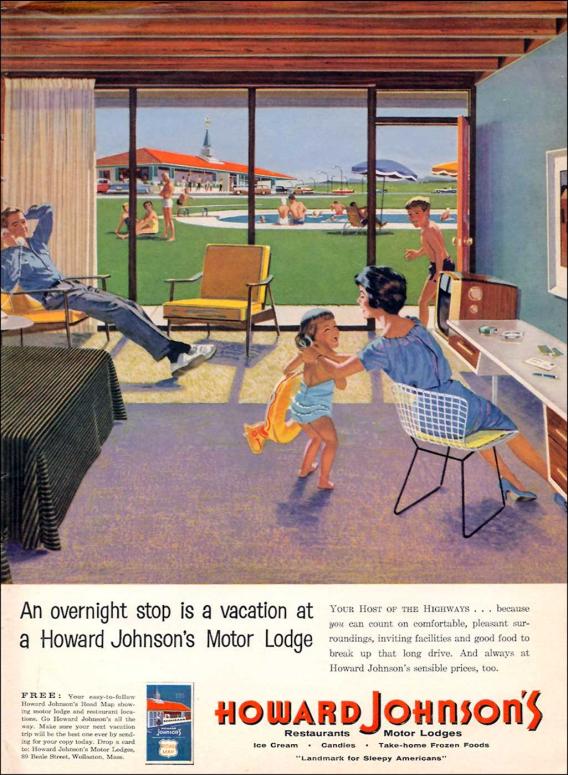

My father’s Polaroid cameras now gather dust in a dark closet. Like the orange-roofed Howard Johnson’s restaurants and “motor lodges” to which my family repaired each time we went on vacation, they are relics of the happy childhood for which I will forever be grateful. But just as Howard Johnson’s shuttered its remaining restaurants years ago, so did Polaroid stop making film in 2008, in the process turning my father’s once-treasured cameras into handsome pieces of junk, relegated to irrelevance, like the Polaroid Corporation itself, by the coming of digital photography.

My father’s Polaroid cameras now gather dust in a dark closet. Like the orange-roofed Howard Johnson’s restaurants and “motor lodges” to which my family repaired each time we went on vacation, they are relics of the happy childhood for which I will forever be grateful. But just as Howard Johnson’s shuttered its remaining restaurants years ago, so did Polaroid stop making film in 2008, in the process turning my father’s once-treasured cameras into handsome pieces of junk, relegated to irrelevance, like the Polaroid Corporation itself, by the coming of digital photography.

As for my Swinger, I’ve no idea what happened to it, but I still remember the jingle that Polaroid used to sell it back in 1965: It’s more than a camera/It’s almost alive/It’s only nineteen dollars and ninety-five. That’s $140.34 in today’s dollars, pretty serious money for a Christmas present in Smalltown, U.S.A. It’s sad to think that such a costly gift should have gone the way of all insufficiently loved toys. I wish my father were still around for me to tell him how much it meant to me once upon a time.