• In TheaterMania: Satchmo at the Waldorf

• In Broadway World: Satchmo at the Waldorf Jazzes at The Long Wharf

Archives for October 16, 2012

TT: When docudramas were true

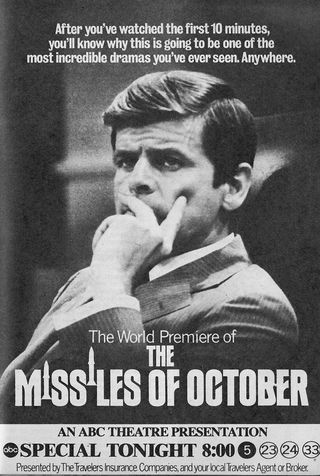

My Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, which normally runs every other Friday, is being published in today’s paper to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis. In it I write about The Missiles of October, the 1974 TV docudrama about the crisis. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Most historians regard docudramas with extreme suspicion–as well they should. From “Inherit the Wind” to Oliver Stone’s “JFK” to “Stuff Happens,” David Hare’s 2004 play about Gulf War II, most of the best-known examples of the genre, in which a screenwriter or playwright takes a well-documented historical event and fictionalizes it, are tendentious to the point of outright falsity. But the rotten barrel of docudrama also contains a few good apples, and one of them, “The Missiles of October,” deserves to be celebrated this week, a half-century after the Cuban Missile Crisis was set in motion by the Pentagon’s discovery that the Soviet Union was moving nuclear missiles into Cuba.

Most historians regard docudramas with extreme suspicion–as well they should. From “Inherit the Wind” to Oliver Stone’s “JFK” to “Stuff Happens,” David Hare’s 2004 play about Gulf War II, most of the best-known examples of the genre, in which a screenwriter or playwright takes a well-documented historical event and fictionalizes it, are tendentious to the point of outright falsity. But the rotten barrel of docudrama also contains a few good apples, and one of them, “The Missiles of October,” deserves to be celebrated this week, a half-century after the Cuban Missile Crisis was set in motion by the Pentagon’s discovery that the Soviet Union was moving nuclear missiles into Cuba.

Written by Stanley R. Greenberg and telecast on ABC in 1974, “The Missiles of October,” which is now available on DVD and on YouTube, was a new type of full-length prime-time TV docudrama. Prior to that time, network TV had dabbled with some frequency in the fictionalization of history, most notably with Abby Mann’s “Judgment at Nuremberg,” which was originally written in 1959 for “Playhouse 90.” But Mr. Greenberg, unlike Mr. Mann and the vast majority of his predecessors, tried to stick as closely as possible to the facts as they were known at the time. Not only did he base his script on “Thirteen Days,” Bobby Kennedy’s posthumously published memoir of the crisis, but “The Missiles of October” opens with an announcement that leaves the viewer in no doubt of his intention to play it straight: “The names we use are real. The action is based upon the historical record as drawn from reportage, academic studies, eyewitness accounts, and official documents.”

Mr. Greenberg’s determination to hew as closely as possible to the record explains in large part why “The Missiles of October” is so much more believable than the Kevin Costner vehicle “Thirteen Days,” the 2000 film version of the same story. Scarcely less central to its impact, though, is the bare-bones way in which it was produced. Anthony Page, the director, shot “The Missiles of October” not on film but videotape, thus giving it a you-are-there crispness, and used dirt-plain interior sets reminiscent of what you might have expected to see in a medium-to-low-budget stage play–or a classic ’50s live-TV drama…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Watch The Missiles of October:

President Kennedy’s actual 1962 Oval Office speech, in which he told viewers that the Soviet Union was moving nuclear weapons into Cuba:

TT: Lookback

From 2005:

From 2005:

Was it a great performance, or merely a great occasion? Falstaff, after all, is no knockabout farce but one of Western art’s most searching commentaries on the vanity of human wishes, no less so because it says what it has to say with a smile. What makes Verdi’s Falstaff immortal is the comic finality with which his remaining delusions of potency are dispelled–and the nobleman’s grace with which he accepts his reversal of fortune. Verdi, who was seventy-nine years old when he completed Falstaff, understood such matters in his bones, which is why Falstaff is the most Shakespearean of all operas. Sir John may be a fool to chase after Alice and Meg, but if he is, so are we all…

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“I suppose there is no word quite as evocative in the English language as ‘home,’ especially if you don’t have one.”

Richard Burton, diary entry, Aug. 22, 1969