Paul Moravec and I were dining at an outdoor café in Manhattan on a balmy spring night a couple of years ago. It was a few months after the premiere of The Letter in Santa Fe. I’d just finished the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf, and I was trying to explain to Paul how surprising and strange it felt for me to have written a play.

Paul Moravec and I were dining at an outdoor café in Manhattan on a balmy spring night a couple of years ago. It was a few months after the premiere of The Letter in Santa Fe. I’d just finished the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf, and I was trying to explain to Paul how surprising and strange it felt for me to have written a play.

“You just wrote an opera libretto, for God’s sake,” he said. “That’s almost like a play, isn’t it?”

“Kind of,” I replied. “But it didn’t really feel like that was what I was doing. I felt more like an editor–like I was doing a really sophisticated editing job on Somerset Maugham’s play, if you know what I mean.”

“That’s bullshit,” he said, not unkindly. “You’re an artist now, and you need to start thinking of yourself that way.”

I’ve spent the past two years trying to come to terms with Paul’s directive. Mrs. T has long been sure that there was more to me than I thought–I would never have gotten up the nerve to write The Letter had it not been for her–but it wasn’t until recently that I began to start thinking of myself, however tentatively, as an artist.

In the two years since I finished the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf, I’ve collaborated with Paul on a second opera, Danse Russe, and written two more plays of my own. Satchmo was premiered in Florida last fall, and a much-revised version of the play will soon be staged by two New England theater companies. Yet in spite of these undertakings, I continued to have difficulties seeing myself as anything other than a critic, a professional appreciator without creative powers of my own. Whenever I tried to tell people about the inexplicable thing that was happening to me, I felt obliged to resort to a grotesque metaphor. “It feels as if I’ve grown another arm,” I’d say.

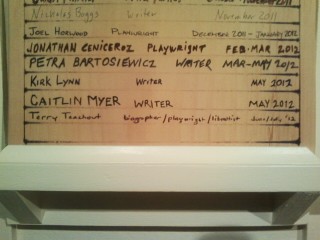

Coming to the MacDowell Colony was a turning point in this process. Five weeks ago I withdrew from the world and drove to a secluded woodland retreat in New Hampshire, where I found myself in the company of some thirty-odd professional artists. I presented myself to them as a fellow artist and was accepted as one. I spent eight or more hours each day working in turn on a biography, a play, and an opera libretto. My closest friends were a poet, a filmmaker, two installation artists, an avant-garde visual artist of ambiguous genre, and a dancer turned law professor. A couple of weeks ago I even acted (in a manner of speaking) in a reading of the first scene of an unfinished play by another colonist. My character, appropriately enough, was a failed actor d’un âge certain who had just written his first play.

Coming to the MacDowell Colony was a turning point in this process. Five weeks ago I withdrew from the world and drove to a secluded woodland retreat in New Hampshire, where I found myself in the company of some thirty-odd professional artists. I presented myself to them as a fellow artist and was accepted as one. I spent eight or more hours each day working in turn on a biography, a play, and an opera libretto. My closest friends were a poet, a filmmaker, two installation artists, an avant-garde visual artist of ambiguous genre, and a dancer turned law professor. A couple of weeks ago I even acted (in a manner of speaking) in a reading of the first scene of an unfinished play by another colonist. My character, appropriately enough, was a failed actor d’un âge certain who had just written his first play.

Toward the end of my stay, I confessed my continuing uncertainties to one of my new friends. “I come from a small town, just like you, and for years I felt like it was a privilege to be an artist, like I didn’t really deserve it,” she told me. “That was how I was raised. Then I met a woman from Sweden who told me, ‘My dear, being an artist is your job.’ And I knew she was right.”

I have no desire whatsoever to give up my own twin jobs as a critic and biographer, which I find deeply and endlessly fulfilling. At the same time, though, I want very much to continue doing my new work, and to continue collaborating with other people to bring it to fruition through the act of performance. Just as one of the most gratifying parts of being at MacDowell was keeping company with artists, so is collaboration one of the most gratifying parts of becoming a theater artist. It might even be the best part.

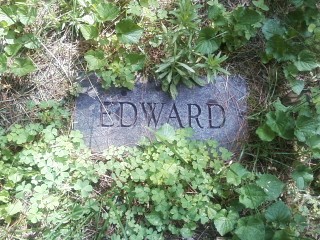

On the night before she left MacDowell and returned to the outside world, my friend said to me, “Be sure to walk down the road to look at the MacDowell graves before you go–and don’t forget to read the plaque.” I knew what she meant. Edward MacDowell and his wife Marian, who turned their Peterborough farm into the MacDowell Colony a century ago, are buried in a woodland clearing a few steps from Colony Hall. This is what the plaque at the entrance to the clearing says:

On the night before she left MacDowell and returned to the outside world, my friend said to me, “Be sure to walk down the road to look at the MacDowell graves before you go–and don’t forget to read the plaque.” I knew what she meant. Edward MacDowell and his wife Marian, who turned their Peterborough farm into the MacDowell Colony a century ago, are buried in a woodland clearing a few steps from Colony Hall. This is what the plaque at the entrance to the clearing says:

Buried on this site are noted composer Edward MacDowell (1860-1908) and his wife, Marian Nevins MacDowell (1857-1956). The composer often paused at this boulder to watch the sun set behind Mount Monadnock. Edward and Marian purchased a small farm and moved to Peterborough in 1896. Together they founded the MacDowell Colony in 1907, the first and leading residency program for artists in the United States. On the acres to the north and west of this site, the MacDowell Colony continues to offer talented artists ideal working conditions in which they can produce enduring works of the imagination.

My friend was struck by the last five words of that inscription. Enduring works of the imagination: that’s what we come here hoping to create. Nearly all of us will fail, of course, for failure is in the nature of artistic endeavor. But we’re here to try. The trying is the point of our coming. It’s our job.

Yesterday morning I loaded up my car and went to breakfast, where I said goodbye to my fellow colonists. Afterward I walked to the MacDowell graves, which are just off the narrow road that runs past Colony Hall. I sat for a long time on a nearby stone bench. As I listened to the birds singing in the trees, I thought about the miracle that has happened to me. Then I walked through the woods to the car, picked up Mrs. T at the Peterborough motel where she’d spent the night, and drove back to the world.

Yesterday morning I loaded up my car and went to breakfast, where I said goodbye to my fellow colonists. Afterward I walked to the MacDowell graves, which are just off the narrow road that runs past Colony Hall. I sat for a long time on a nearby stone bench. As I listened to the birds singing in the trees, I thought about the miracle that has happened to me. Then I walked through the woods to the car, picked up Mrs. T at the Peterborough motel where she’d spent the night, and drove back to the world.