Miranda Carter, Anthony Blunt: His Lives. Originally published in 2001, this comprehensively informed, smartly written biography tells the believe-it-or-not tale of the Cambridge graduate, distinguished art scholar, royal courtier, and not-entirely-closeted gay who spied for the Russians, then was stripped of his knighthood when Margaret Thatcher blew the whistle on the deepest and darkest of his secret lives. Carter brings off the near-miracle of being just sympathetic enough–Blunt was a genuinely tortured soul–without falling into the fatal mistake of whitewashing the evil that he did. Engrossing, enthralling, horrifying (TT).

Archives for July 24, 2012

DVD/BLU-RAY

Margaret (Fox Searchlight, two discs). Kenneth Lonergan’s masterpiece, the wrenching story of how a seventeen-year-old New Yorker (Anna Paquin) is brought face to face with the terrible fragility of life. Because Margaret nearly vanished without trace–it was only seen in a handful of theaters–the release of the film on home video is by definition a major event. Anyone who was moved by Lonergan’s You Can Count on Me will be shaken to the core by Margaret. The Blu-ray disc contains the shorter theatrical version, the DVD the full-length extended cut (TT).

EXHIBITION

Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series (Corcoran Gallery, 500 Seventeenth St. NW, Washington, D.C., up through Sept. 23). Seventy-five abstract paintings and works on paper made by Diebenkorn between 1967 and 1987, the years when he was creating the most original works of his career in a studio in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica. This brilliantly curated show is one of the most satisfying museum retrospectives ever devoted to an American artist. You must see it, no matter how far you have to travel to get there (TT).

CD

Classic Coleman Hawkins Sessions 1922-1947 (Mosaic, eight CDs). An overflowing cornucopia of key recordings by the de facto inventor of jazz saxophone, exquisitely remastered from the original 78 sides. Loren Schoenberg’s masterly liner notes are worth the price of the package all by themselves (TT).

PLAY

Tribes (Barrow Street Theatre, 27 Barrow St., closes Jan. 6). A well-wrought drama by Nina Raines about a self-consciously arty family of compulsive talkers whose youngest member (Russell Harvard) is deaf. David Cromer’s theater-in-the-round staging maximizes the considerable strengths of Tribes (including its biting, often brutal humor). Not only is it the best show in New York, but the off-Broadway run has just been extended into January. What are you waiting for? (TT).

TT: Back to the world

Paul Moravec and I were dining at an outdoor café in Manhattan on a balmy spring night a couple of years ago. It was a few months after the premiere of The Letter in Santa Fe. I’d just finished the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf, and I was trying to explain to Paul how surprising and strange it felt for me to have written a play.

Paul Moravec and I were dining at an outdoor café in Manhattan on a balmy spring night a couple of years ago. It was a few months after the premiere of The Letter in Santa Fe. I’d just finished the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf, and I was trying to explain to Paul how surprising and strange it felt for me to have written a play.

“You just wrote an opera libretto, for God’s sake,” he said. “That’s almost like a play, isn’t it?”

“Kind of,” I replied. “But it didn’t really feel like that was what I was doing. I felt more like an editor–like I was doing a really sophisticated editing job on Somerset Maugham’s play, if you know what I mean.”

“That’s bullshit,” he said, not unkindly. “You’re an artist now, and you need to start thinking of yourself that way.”

I’ve spent the past two years trying to come to terms with Paul’s directive. Mrs. T has long been sure that there was more to me than I thought–I would never have gotten up the nerve to write The Letter had it not been for her–but it wasn’t until recently that I began to start thinking of myself, however tentatively, as an artist.

In the two years since I finished the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf, I’ve collaborated with Paul on a second opera, Danse Russe, and written two more plays of my own. Satchmo was premiered in Florida last fall, and a much-revised version of the play will soon be staged by two New England theater companies. Yet in spite of these undertakings, I continued to have difficulties seeing myself as anything other than a critic, a professional appreciator without creative powers of my own. Whenever I tried to tell people about the inexplicable thing that was happening to me, I felt obliged to resort to a grotesque metaphor. “It feels as if I’ve grown another arm,” I’d say.

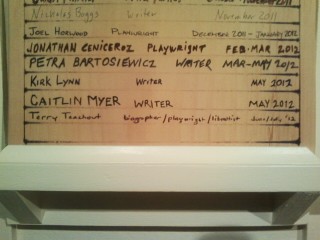

Coming to the MacDowell Colony was a turning point in this process. Five weeks ago I withdrew from the world and drove to a secluded woodland retreat in New Hampshire, where I found myself in the company of some thirty-odd professional artists. I presented myself to them as a fellow artist and was accepted as one. I spent eight or more hours each day working in turn on a biography, a play, and an opera libretto. My closest friends were a poet, a filmmaker, two installation artists, an avant-garde visual artist of ambiguous genre, and a dancer turned law professor. A couple of weeks ago I even acted (in a manner of speaking) in a reading of the first scene of an unfinished play by another colonist. My character, appropriately enough, was a failed actor d’un âge certain who had just written his first play.

Coming to the MacDowell Colony was a turning point in this process. Five weeks ago I withdrew from the world and drove to a secluded woodland retreat in New Hampshire, where I found myself in the company of some thirty-odd professional artists. I presented myself to them as a fellow artist and was accepted as one. I spent eight or more hours each day working in turn on a biography, a play, and an opera libretto. My closest friends were a poet, a filmmaker, two installation artists, an avant-garde visual artist of ambiguous genre, and a dancer turned law professor. A couple of weeks ago I even acted (in a manner of speaking) in a reading of the first scene of an unfinished play by another colonist. My character, appropriately enough, was a failed actor d’un âge certain who had just written his first play.

Toward the end of my stay, I confessed my continuing uncertainties to one of my new friends. “I come from a small town, just like you, and for years I felt like it was a privilege to be an artist, like I didn’t really deserve it,” she told me. “That was how I was raised. Then I met a woman from Sweden who told me, ‘My dear, being an artist is your job.’ And I knew she was right.”

I have no desire whatsoever to give up my own twin jobs as a critic and biographer, which I find deeply and endlessly fulfilling. At the same time, though, I want very much to continue doing my new work, and to continue collaborating with other people to bring it to fruition through the act of performance. Just as one of the most gratifying parts of being at MacDowell was keeping company with artists, so is collaboration one of the most gratifying parts of becoming a theater artist. It might even be the best part.

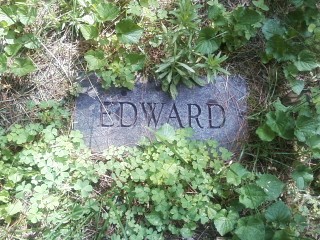

On the night before she left MacDowell and returned to the outside world, my friend said to me, “Be sure to walk down the road to look at the MacDowell graves before you go–and don’t forget to read the plaque.” I knew what she meant. Edward MacDowell and his wife Marian, who turned their Peterborough farm into the MacDowell Colony a century ago, are buried in a woodland clearing a few steps from Colony Hall. This is what the plaque at the entrance to the clearing says:

On the night before she left MacDowell and returned to the outside world, my friend said to me, “Be sure to walk down the road to look at the MacDowell graves before you go–and don’t forget to read the plaque.” I knew what she meant. Edward MacDowell and his wife Marian, who turned their Peterborough farm into the MacDowell Colony a century ago, are buried in a woodland clearing a few steps from Colony Hall. This is what the plaque at the entrance to the clearing says:

Buried on this site are noted composer Edward MacDowell (1860-1908) and his wife, Marian Nevins MacDowell (1857-1956). The composer often paused at this boulder to watch the sun set behind Mount Monadnock. Edward and Marian purchased a small farm and moved to Peterborough in 1896. Together they founded the MacDowell Colony in 1907, the first and leading residency program for artists in the United States. On the acres to the north and west of this site, the MacDowell Colony continues to offer talented artists ideal working conditions in which they can produce enduring works of the imagination.

My friend was struck by the last five words of that inscription. Enduring works of the imagination: that’s what we come here hoping to create. Nearly all of us will fail, of course, for failure is in the nature of artistic endeavor. But we’re here to try. The trying is the point of our coming. It’s our job.

Yesterday morning I loaded up my car and went to breakfast, where I said goodbye to my fellow colonists. Afterward I walked to the MacDowell graves, which are just off the narrow road that runs past Colony Hall. I sat for a long time on a nearby stone bench. As I listened to the birds singing in the trees, I thought about the miracle that has happened to me. Then I walked through the woods to the car, picked up Mrs. T at the Peterborough motel where she’d spent the night, and drove back to the world.

Yesterday morning I loaded up my car and went to breakfast, where I said goodbye to my fellow colonists. Afterward I walked to the MacDowell graves, which are just off the narrow road that runs past Colony Hall. I sat for a long time on a nearby stone bench. As I listened to the birds singing in the trees, I thought about the miracle that has happened to me. Then I walked through the woods to the car, picked up Mrs. T at the Peterborough motel where she’d spent the night, and drove back to the world.

TT: Lookback

From 2005:

From 2005:

I love New York, but I couldn’t even begin to pass for a native, even when I don my All-Black Outfit and venture south of Theatre Row, or put on a suit for an opening night. People with backgrounds like mine have been known to retreat into snobbery in order to conceal their origins, but I’m homemade and proud to be. Oscar Wilde said that a cynic was someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing, which suggests that a snob might be someone who appreciates the prestige of everything and the beauty of nothing. That’s not me….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“His imagination resembled the wings of an ostrich. It enabled him to run, though not to soar.”

Thomas Macaulay, “On John Dryden”