In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review a Chicago-area show, Writers’ Theatre’s superlative revival of A Little Night Music. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

When Writers’ Theatre, a Chicago-area company that operates out of a 108-seat house, announced that it would try its hand at “A Little Night Music,” I decided at once to go, and can now report that William Brown, who directed the company’s unforgettable 2011 revival of “Heartbreak House,” has outdone himself. While first-class small-house stagings of “A Little Night Music” are no longer rare, this one tops them all.

Kevin Depinet, whose long list of memorable design credits includes Chicago Shakespeare’s “Follies” and the Goodman Theatre’s recent revival of “The Iceman Cometh,” has conjured up the simplest of sets, a two-step platform framed by elegant-looking curtains. The wide-open playing area is a pebble’s throw from the audience. As a result, the members of the cast never have to exaggerate: Not only is every word audible down to the last “and/or,” but every thrown-away gesture registers like a pistol shot in a walk-in closet. Mr. Brown’s exemplary actors can thus scale their performances down to the point where you feel as though you’re not hearing Mr. Sondheim’s songs so much as overhearing them. Moreover, the sheer sexiness of “A Little Night Music” (which is, among other things, a musical about the difference between sex and love) comes across with breath-catching directness.

Kevin Depinet, whose long list of memorable design credits includes Chicago Shakespeare’s “Follies” and the Goodman Theatre’s recent revival of “The Iceman Cometh,” has conjured up the simplest of sets, a two-step platform framed by elegant-looking curtains. The wide-open playing area is a pebble’s throw from the audience. As a result, the members of the cast never have to exaggerate: Not only is every word audible down to the last “and/or,” but every thrown-away gesture registers like a pistol shot in a walk-in closet. Mr. Brown’s exemplary actors can thus scale their performances down to the point where you feel as though you’re not hearing Mr. Sondheim’s songs so much as overhearing them. Moreover, the sheer sexiness of “A Little Night Music” (which is, among other things, a musical about the difference between sex and love) comes across with breath-catching directness.

Such a presentation demands a cast whose members are capable of taking full advantage of their close proximity to the audience. Mr. Brown has assembled a team that is uniformly up to the challenge. It’s no slight to her colleagues, though, to say that Shannon Cochran, who plays Desirée Armfeldt, the much-bedded actress who longs for a bit of quiet comfort in her middle age, is the brightest star of the night. Ms. Cochran, who was stunning in Long Wharf Theatre’s 2006 revival of “Private Lives” and the 2008 production of “The Lion in Winter” that introduced me to Writers’ Theatre, proves to be a first-class singer as well. You’ll never hear a more powerfully affecting performance of “Send in the Clowns,” or be more touched by the way in which she chastises to the idealistic Henrik (Royen Kent) with the gentle disillusion of a woman who knows too much….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The trailer for Writers’ Theatre’s A Little Night Music:

Archives for July 6, 2012

TT: Forged in sorrow, cloven by anger

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I write about the Louvin Brothers. Here’s an excerpt.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I write about the Louvin Brothers. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Family acts have long exerted a powerful pull on audiences. Whether it’s a brother-and-sister musical duo like Yehudi and Hephzibah Menuhin or a husband-and-wife acting team like Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, it’s irresistibly fascinating to see them perform together on stage. When they get along–and sometimes even when they don’t–they very often give the uncanny impression of being able to think, move or sing like a single person. Alas, such acts are no longer as common in the music business as they used to be, perhaps because families aren’t as close as they used to be. Nor have they ever been all that common in classical music. It is in the field of pop music that family members are far more likely to collaborate, and it is in country music that they have left the deepest mark.

Why is this so? Because many country musicians were children of the Great Depression who were born into poor rural families. If they wanted to hear music, they usually had to make it themselves, and if they did it well enough, they had a chance to lift themselves out of poverty. What’s more, it’s natural enough for siblings who make music together as children to keep on doing so in adulthood.

Brother acts have usually been more popular in country music than sister or husband-and-wife acts, and none has been more admired or influential than the Louvin Brothers, who cut their first record in 1947. Like many sibling acts, they were a match made in hell, so much so that Ira Louvin’s violent, alcohol-fueled temper finally led his younger brother Charlie to break up the duo in 1963, two years before Ira died in a car crash. But you’d never have guessed it from hearing them sing together, for their high, hard-bitten voices wound round one another in harmonies so closely woven that you couldn’t always tell which brother was singing what part.

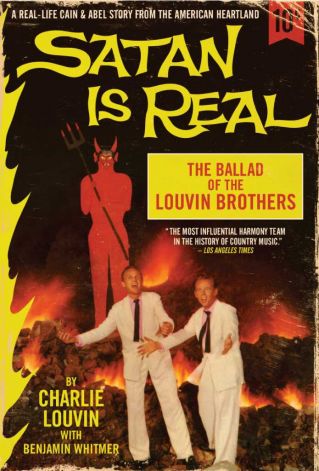

Two months before his own death in 2011, Charlie Louvin finished work on a memoir that was published earlier this year. “Satan Is Real: The Ballad of the Louvin Brothers” (Igniter/HarperCollins), which has the rough-hewn sound of a real person swapping stories after hours, is one of the most important and illuminating memoirs ever written by a country singer. Not only is it as readable as a first-rate novel, but “Satan Is Real,” which is named after the Louvin Brothers’ best-known album, a 1959 collection of gospel songs, offers urbanites a joltingly vivid glimpse of what it was like to grow up on a Depression-era farm….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The Louvin Brothers sing “I Can’t Keep You in Love With Me” on Pet Milk Grand Ole Opry in 1961:

TT: Almanac

“All truths are not to be told.”

George Herbert, Jacula Prudentum