My recent visit to the Orange County Museum of Art’s Richard Diebenkorn retrospective has yielded up a “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

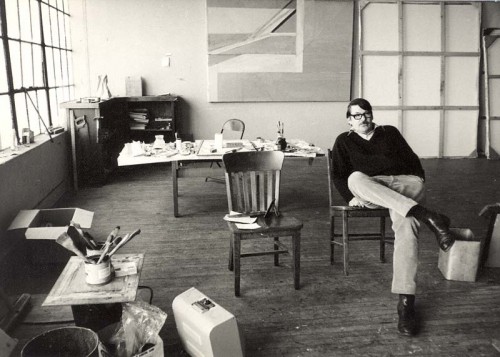

One of the most satisfying museum retrospectives ever devoted to an American artist is now traveling from coast to coast. “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series,” which closed at California’s Orange County Museum of Art two weeks ago and will reopen on June 30 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., consists of 75-odd abstract paintings and works on paper made by Diebenkorn between 1967 and 1987, the years when he worked out of a studio in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica….

One of the most satisfying museum retrospectives ever devoted to an American artist is now traveling from coast to coast. “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series,” which closed at California’s Orange County Museum of Art two weeks ago and will reopen on June 30 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., consists of 75-odd abstract paintings and works on paper made by Diebenkorn between 1967 and 1987, the years when he worked out of a studio in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica….

Part of what makes the Ocean Park series so fascinating is that Diebenkorn, who died in 1993, waged a lifelong “battle” with abstraction. He started out as a gifted abstract-expressionist painter. In 1955 he suddenly embraced representation, turning out dozens of figurative paintings that translate the language of Matisse into a wholly personal, semi-abstract style. Then, in the Ocean Park series, he made a decisive return to abstraction, in the process creating the most original works of his career.

To chart Diebenkorn’s stylistic development is to be reminded of the near-overwhelming power of the idea of abstraction in the 20th century. It was even felt by artists who, like Pierre Bonnard and Fairfield Porter, never produced an abstract painting in their lives, but were nonetheless influenced by the way in which practitioners of abstraction created what Diebenkorn called “invented landscapes,” non-objective images that evoked the world of tangible reality while steering clear of literal representation.

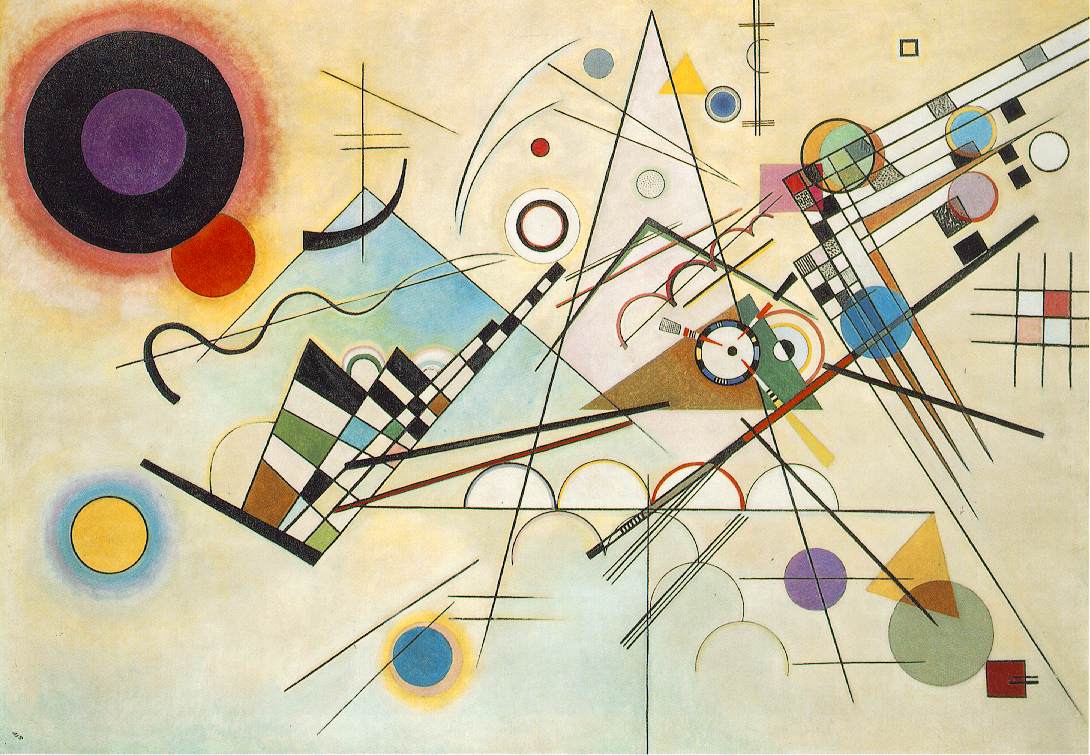

The idea of abstraction is so central to the history of modern art that it left its mark on the work of non-visual artists as well. George Balanchine, for example, is best remembered for the many “plotless” ballets that he made to the music of Igor Stravinsky. The Russian-born choreographer never used the word “abstract” to describe them. “Dancer is not a color,” he said. “Dancer is a person.” But to look at a dance like “Stravinsky Violin Concerto,” in which still-recognizable human relationships are stripped of all literal meaning, is to suspect that Balanchine saw in his youth at least some of the innovative canvases in which Vasily Kandinsky, his fellow countryman, dispensed with the pictorial restrictions of figurative art to become the first abstract painter….

The idea of abstraction is so central to the history of modern art that it left its mark on the work of non-visual artists as well. George Balanchine, for example, is best remembered for the many “plotless” ballets that he made to the music of Igor Stravinsky. The Russian-born choreographer never used the word “abstract” to describe them. “Dancer is not a color,” he said. “Dancer is a person.” But to look at a dance like “Stravinsky Violin Concerto,” in which still-recognizable human relationships are stripped of all literal meaning, is to suspect that Balanchine saw in his youth at least some of the innovative canvases in which Vasily Kandinsky, his fellow countryman, dispensed with the pictorial restrictions of figurative art to become the first abstract painter….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from Balanchine, a 1984 PBS documentary narrated by Frank Langella, in which George Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky are seen in conversation. The clip includes excerpts from three Balanchine-Stravinsky ballets, Agon, Balustrade, and Stravinsky Violin Concerto:

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog