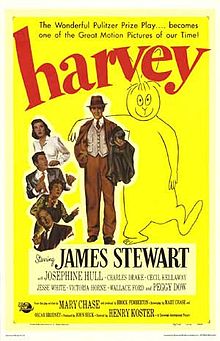

In tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal I’ll be reviewing the Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Harvey, Mary Chase’s 1944 play about a fellow named Elwood P. Dowd who claims that his best friend is a six-foot-tall rabbit. It’s easy to forget how popular and admired Harvey once was. Not only did it win the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for drama, but the original production ran on Broadway for 1,775 performances, after which Hollywood turned Harvey into a film starring James Stewart.

In tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal I’ll be reviewing the Roundabout Theatre Company’s revival of Harvey, Mary Chase’s 1944 play about a fellow named Elwood P. Dowd who claims that his best friend is a six-foot-tall rabbit. It’s easy to forget how popular and admired Harvey once was. Not only did it win the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for drama, but the original production ran on Broadway for 1,775 performances, after which Hollywood turned Harvey into a film starring James Stewart.

It was Frank Fay, not Stewart, who created the role of Elwood P. Dowd on Broadway. But Stewart liked the play enough to replace Fay in the original Broadway production two years into its run, and in addition to starring in the 1950 film version, he also starred in the 1970 Broadway revival and a subsequent Hallmark Hall of Fame TV version that aired in 1972. As a result, Stewart is to this day closely identified with Harvey, a fact that in his lifetime bemused him:

Wherever I go I’m always asked about Harvey, about how he is and where he is. At first I thought it was a joke but then I could see people were serious. So I just say that he’s home with a cold and that I’ll pass along the regards. Harvey’s had a big effect on my life.

But even though Harvey continues to receive a fair number of amateur performances, professional stagings of the play have become increasingly rare. The 1970 production was the last time it was done on Broadway prior to the Roundabout revival. I’ve been covering theater for the Journal since 2003, and the preview of Harvey that I saw last Friday was the first time I’d seen the show on stage in forty years.

It isn’t strictly true to say that I “saw” Harvey forty years ago. In fact, I appeared in a high-school production, playing the supporting role of Dr. Chumley, the proprietor of Chumley’s Rest, the impeccably genteel insane asylum to which Elwood P. Dowd’s sister and niece are endeavoring to have him committed. It was one of five shows in which I acted in high school and college (the others, for the record, were Oliver!, The Innocents, The Mousetrap, The Little Foxes, and The Man Who Came to Dinner). While I loved doing theater, I finally figured out for myself that I was a mediocre actor, thus saving myself a lifetime of frustration. After 1978 I never again set foot on a theatrical stage, at least not while the curtain was up.

It never occurred to me in 1978, or in 1998, that I was destined to spend my middle age as a drama critic, much less that I would someday write shows of my own. If you’d told me that my first play would eventually receive back-to-back productions at two well-known regional theater companies, I would have laughed in your face. Yet theater was immensely important to me in high school and college, a fact that I later tried to explain when I wrote a memoir of my boyhood and youth in which I described my first theatrical outing:

I knew that I lacked the physical presence that is as basic to the young actor as the ability to tell one note from another is to the young musician. I probably would have done just as well trying out for the football team. But I was drawn to the stage in spite of everything, and for a perfectly good reason: I wanted to try being somebody else for a change….

It was still me on that little stage, and everybody knew it, myself included. But something far more important happened during the six weeks we spent in rehearsal: I got my first taste of the intimacy shared by the cast and crew of a play. We spent long nighttime hours working together in a cavernous building into which no stranger was allowed to set foot. We concentrated intensely on each other on stage and talked endlessly to each other off stage, exchanging the self-conscious confidences of adolescence in the shadowy corners of the gym. After every dress rehearsal and every performance, we drove to Sambo’s, an all-night restaurant on the edge of town, and we went with faces unwashed and makeup intact, that being the badge of membership in the most exclusive fraternity in town.

I can’t remember the last time I saw any of the people involved in the Harlequin Players’ production of Harvey, though I do know that one of them, the star of the show, died of AIDS many years ago. But Barbara Brown, the English teacher who led the Harlequin Players and directed the show, popped up on my Facebook page two days before The Letter, my first opera, opened in Santa Fe, and we’ve been in touch ever since.

When I mentioned last week on Facebook that I’d just gotten back from a preview of Harvey, Barbara posted as follows: “And what a great Dr. Chumley you were!” I doubt that, though it was sweet of her to say so. I can, however, vouch for the fact that I remembered every word of the last act of Harvey, and even muttered a few lines of the script under my breath, much to the amusement of the young friend who saw the show with me.

Above all–and not at all surprisingly–I remembered my own big third-act scene, in which Dr. Chumley is informed by Elwood P. Dowd that Harvey has the power to “look at your clock and stop it,” thereby allowing you to “go away as long as you like with whomever you like and go as far as you like.” The doctor, who has been grappling vainly with what we now call a midlife crisis, then confesses that he knows exactly where he’d go and what he’d do:

Above all–and not at all surprisingly–I remembered my own big third-act scene, in which Dr. Chumley is informed by Elwood P. Dowd that Harvey has the power to “look at your clock and stop it,” thereby allowing you to “go away as long as you like with whomever you like and go as far as you like.” The doctor, who has been grappling vainly with what we now call a midlife crisis, then confesses that he knows exactly where he’d go and what he’d do:

There’s a cottage camp outside Akron in a grove of maple trees, cool, green, beautiful. I’d go there with a pretty young woman, a strange woman, a quiet woman. I wouldn’t even want to know her name. I would be–Dr. Brown. I’d send out for cold beer. I would talk to her. I’d tell her things I have never told anyone–things that are locked in here. And then I’d send out for more cold beer. I wouldn’t let her talk to me, but as I talked I would want her to reach out a soft white hand and stroke my head and say, “Poor thing! Oh, you poor, poor thing!”

Needless to say, I was far too young to appreciate the very real pathos that lies just beneath the surface of this wonderfully silly little scene. But I understand it now, and it was decidedly unsettling to watch it unfold on the stage of the American Airlines Theatre a few weeks after the death of my mother, who loved the film version of Harvey and was proud beyond words to see me playing Dr. Chumley forty years ago.

As I rode down to Broadway, I felt (as I always do) the reflexive impulse to call my mother (as I always did) and tell her where I was going. And as I watched the Akron scene, I thought (as I always will) of how very much I wish I had a six-foot-tall rabbit who could make it possible for me to call my mother one more time and tell her where I’d been.

After the show, I texted my brother: “I just saw Harvey on Broadway. You can imagine how I feel.”

He responded, as is his concise custom, with one word that let me know that he knew: “Yup.”

* * *

An excerpt from the 1950 film version of Harvey. Dr. Chumley is played by Cecil Kellaway: