As always, I threw myself into work in order to stave off despair. Going to the theater three or four nights a week was as good a way as any to keep my mind occupied, but in between shows I thought the same blunt, ugly thoughts that had come to me at odd moments ever since December. What do I do if she starts to fail while my play is in rehearsal? What’s the closest airport to Lenox? What if it happens on the morning of the dress rehearsal? Or on opening night? I drew up a string of increasingly far-fetched travel options, blithely ignoring the old saying I’d quoted a thousand times: if you want to hear God laugh, make a plan.

The day after the Broadway season ended, my wife and I stuck to one of our longest-standing plans and flew to Chicago so that I could review four shows there. Unlike the lightweight fare that I’d been seeing in New York, they were suited to my mood, at times joltingly so. To watch Angels in America or The Iceman Cometh while waiting for your mother to die is not an experience for the faint of heart.

The day after the Broadway season ended, my wife and I stuck to one of our longest-standing plans and flew to Chicago so that I could review four shows there. Unlike the lightweight fare that I’d been seeing in New York, they were suited to my mood, at times joltingly so. To watch Angels in America or The Iceman Cometh while waiting for your mother to die is not an experience for the faint of heart.

I called my brother from Chicago each night. He said the same thing every time: “She’s really weak, but the hospice nurses don’t think it’s going to happen right away.”

We returned to the East Coast on Friday and headed for our little farmhouse in Connecticut, hoping to spend the weekend getting some rest in preparation for what was to come. I was supposed to drive down to New Haven on Monday to be on hand when Long Wharf Theatre announced that Satchmo at the Waldorf would be produced there in October, but I had a feeling that this plan, unlike its predecessors, might be destined to go awry, and so it did. My brother called on Saturday night. “I think you’d probably better get here as soon as you can,” he said, sounding as weary as I felt.

It was too late to fly to St. Louis that night from anywhere in New England, so we stayed up until three in the morning, then went to the Hartford airport. A couple of hours later we flew down to Washington, changed planes for Memphis, picked up a rental car, and headed north toward Smalltown. As I drove, I thought of the day that my father died. I’d been in Washington on business, and by the time my brother called to summon me home, the last flight to St. Louis had left. I flew out the next morning and reached my father’s hospital room a half hour too late.

Ever since then I’d feared–assumed, really–that the same thing would happen when my mother died, and after I started covering regional theater performances throughout the country, I knew that it was now more than likely. This knowledge filled me with guilt, albeit of an ironic kind. My mother was fiercely proud of the things I did after I left home, but she also knew that it was leaving home that had made it possible for me to do them, and impossible for me to be with her more than occasionally. I never asked her if she thought I’d made the right choice. I think I was afraid of what she might say.

Ever since then I’d feared–assumed, really–that the same thing would happen when my mother died, and after I started covering regional theater performances throughout the country, I knew that it was now more than likely. This knowledge filled me with guilt, albeit of an ironic kind. My mother was fiercely proud of the things I did after I left home, but she also knew that it was leaving home that had made it possible for me to do them, and impossible for me to be with her more than occasionally. I never asked her if she thought I’d made the right choice. I think I was afraid of what she might say.

* * *

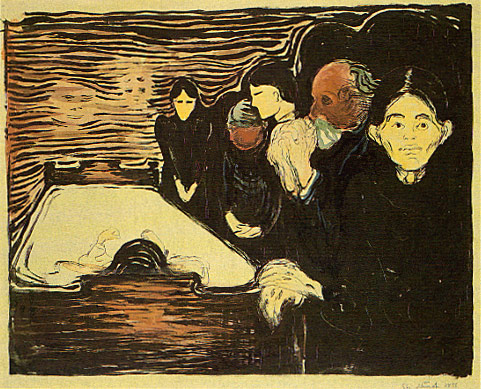

We got to the nursing home at one-thirty. The rest of the family had already gathered in my mother’s room. She was unconscious. A few muttered words from the hospice nurse told me all I needed to know. She was breathing rapidly and shallowly and her pulse was galloping. It could only be a matter of time before her heart gave out.

If you’ve never been present at the deathbed of a friend or family member, you might well be startled, even shocked, by what you see there. We have it on the best authority that humankind cannot bear very much reality, and no matter how despondent you may feel, it’s just as hard to stay stiff with sorrow for more than a few minutes at a time. Whispered confidences give way to more or less pleasant conversation, and if the death watch drags on long enough, there’s a good chance that you’ll hear a fair amount of laughter, some of which will almost certainly be yours. My journalist’s ear took in the laughter that day, just as my journalist’s eye saw that the TV in the corner of my mother’s room was tuned to a music channel, and that Frankie Valli was singing “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You” as her minister prayed for her soul. Overly earnest artists are apt to scissor out such grotesque juxtapositions, but rare is the real-life deathbed scene at which they are nowhere to be found.

I laughed, too, but mostly I sat by the bed and watched my mother, stroking her hair and telling her that we all loved her, hoping against hope that she could hear my voice. Her suffering (if she was suffering, since she showed no sign of awareness) continued for several more hours, and though the nurses steadily increased the amount of morphine that they were giving her, it failed to relieve her all-too-visible respiratory distress.

Around nine o’clock the hospice nurse turned to my brother and me. As the room grew still, she explained that in order to bring my mother’s desperately labored breathing under control, she would have to administer a much larger dose. “If we do that, we don’t want you to be surprised by what might happen,” she said.

Around nine o’clock the hospice nurse turned to my brother and me. As the room grew still, she explained that in order to bring my mother’s desperately labored breathing under control, she would have to administer a much larger dose. “If we do that, we don’t want you to be surprised by what might happen,” she said.

The three of us looked at one another. My brother and I nodded in unison. “We understand,” I said. “Go ahead.”

Within a few minutes my mother was breathing much more slowly and easily, and everyone started talking again. I considered going to her house to try and get a few hours’ sleep. Then I noticed that her breathing had grown irregular. I gestured to the nurse. “Apnea,” she said. I decided to stay put.

I took my mother’s hand and told her for the hundredth time that we all loved her, watching her chest grow still, tremble briefly, then start to move again as she caught yet another shallow breath. My brother, our wives, and the nurse watched her no less intently, but no one else in the room seemed to notice what was happening. Her eyes were open for the first time that day, staring blankly at nothing. She seemed almost peaceful, and I felt no fear, only curiosity. I’ve never seen anyone die, I thought, continuing to hold her hand. What will it look like?

It looked like nothing at all. The next breath simply failed to come. I held my own breath in reflexive response, then let it out in a long sigh. A moment later, the nurse moved to the bed, put a stethoscope to her chest, and turned to me without saying a word. I nodded, stood up, kissed my mother’s forehead, and said, “I love you, darling. Goodbye.” I tried to close her eyes, the way I’d always seen it done in movies, but the lids wouldn’t shut.

When I turned away from the empty shell of the woman who gave me life, everyone around me was crying. My brother’s face, until then a rigid mask of self-control, was crumpled with grief. Only my eyes were dry. Under normal circumstances I am the easiest of weepers, but my own grief was buried deep beneath the stony rubble of exhaustion. Whatever I felt was, at least for now, inaccessible to me.

(Second of three parts)

Archives for June 5, 2012

TT: Lookback

From 2006:

From 2006:

Teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom, says the psalmist. I wonder how many of us do, or even try. I nearly died nine months ago, and you’d think that such an sobering experience would cause me to devote my remaining days to none but the most consequential of tasks–but you’d be wrong. A couple of Saturdays ago, for instance, I found myself with no shows to see and no appointments to keep. How did I spend my precious night off? Did I pile up fresh pages of Hotter Than That: A Life of Louis Armstrong? Did I closet myself with a hitherto-unread classic, or listen anew to Op. 111, or spend hour upon hour contemplating the Teachout Museum in breathless silence? No, indeed. I sent out for pizza, curled up on the couch, and watched a pair of perfectly silly movies….

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“You’re only free when both your parents are dead, or so I’ve heard it said. I suppose it means that with your parents gone there is no one left who can still regard you as a child. Or maybe, as in my case, with no kids of my own, it means that family responsibilities are over at last. I don’t really know. All I know is that I was now without any family whatsoever, and it wasn’t freedom I was feeling but an emptiness that went deep down and that I knew I would never be completely able to shake.”

Joseph Epstein, “Family Values” (courtesy of Bobby Franklin)