Michael Holroyd, Bernard Shaw: The One-Volume Definitive Edition. This meticulously revised 864-page redaction of Holroyd’s massive four-volume biography, published in 1997, improves on the original by trimming away the endless digressions, putting the focus squarely on the complex relationship between Shaw’s life and work. Sympathetic but never hagiographic, Bernard Shaw strikes a proper balance between the major and minor plays, makes no excuses for the playwright’s totalitarian inclinations, and tells you everything you need to know in an unfailingly readable way (TT).

Archives for May 25, 2012

DVD

The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond. Budd Boetticher’s 1960 portrait of an ice-cold sociopath (Ray Danton) is a high-velocity gangster film devoid of the slightest trace of sentimentality. Factor in Lucien Ballard’s knowingly old-fashioned cinematography and Leonard Rosenman’s letter-perfect score and you get one of the most satisfying B movies ever made (TT).

DIETRICH FISCHER-DIESKAU: IMPERFECT GREATNESS

“Perfect? By no means. But perfection has a way of becoming boring. Whatever else he was or wasn’t, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was always interesting. He never gave a performance that didn’t make you think–even when it was wrong…”

OGIC: Write a little

Aphorisms are almost the opposite of the kind of writing that typically draws me in, writing that’s absorbed in the particular. But Aaron Haspel’s hard, bright aphorisms, which he recently brought together and called Everything, are abstract and generalizing, yet so precise as to share something of the quality of the gemlike details I swoon over in poems and fiction. They give a startle first that then gives way to recognition. Twitter, where I first read many of them, might have seemed their natural context in a way, but they gain force from being collected together and grouped by theme.

Here are several of my favorites:

No style guide can address the chief defect in writing, which is having nothing to say.

Good critics do not have good taste. They have articulate, consistent taste for which the reader can correct.

Read a lot: think some: write a little.

Influence is plagiarism spread thin.

The less a discipline resembles mathematics, the less likely a clever theory is to be true.

Few experiences are more salutary than losing an argument, but only if you notice.

The parable of the drunk looking for his keys under the street lamp, where the light is better, explains vast swaths of intellectual history.

Efficient search is serendipity’s implacable enemy.

The more you regard your life as a story the more you edit it.

The superstitions of a culture are easily discerned: they are the matters on which everyone agrees.

Low-down, thoroughgoing rottenness often has nice manners.

Your terrible secret is that you have no terrible secret.

Blaming an actor for being a narcissist is like blaming a tiger for being a carnivore.

To manage people effectively you must not only accept but praise work that you could have done better yourself.

A relentlessly cheerful, upbeat, can-do attitude is a highly effective form of bullying.

More successful enterprises have been created for spite than for money.

Humanity for the first time is burdened with a vast proletariat of literate, ambitious, and demanding people who can’t really do anything.

The joy of money lies less in what one does than in what one might do.

The people are flattered more obsequiously than the monarch ever was.

We reserve our warmest admiration, not for what is utterly beyond us, but for what we secretly believe we might have done ourselves on our very best day.

The future will marvel that we regarded “be yourself” as sound moral advice.

Better deceived than distrustful.

Nothing tastes quite like the hand that feeds you.

People will like you if you like them, which is too high a price.

To hate something properly you must have liked it once.

To make an epigram, invert a cliché.

TT: And then there were none

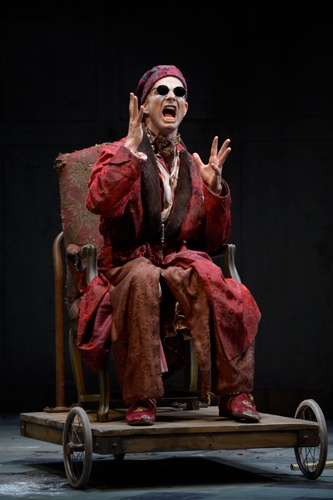

Today’s Wall Street Journal drama column, filed from San Francisco, is devoted in its entirety to the American Conservatory Theater’s revival of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, starring Bill Irwin. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Even among geniuses, there’s no accounting for taste: Samuel Beckett actually thought that “Endgame,” first performed in 1957, was a better play than “Waiting for Godot.” It is, to be sure, one of the key works of postwar European theater, but could it really be better than “Godot,” the most admired and influential play of the 20th century? About that one may take leave to doubt. About American Conservatory Theater’s revival, which stars Bill Irwin, the verdict is far more certain. While Mr. Irwin’s performance is not wholly convincing, it works, and in every other way this is an ideal “Endgame,” smartly cast, sensitively staged and glisteningly faithful to the author’s intentions. Carey Perloff, A.C.T.’s artistic director and the director of this production, has done herself and her company proud.

The play’s not-quite-slapstick is enacted with delicate subtlety in Ms. Perloff’s staging, and Mr. Gabriel’s stiff-legged, sweetly patient and unexpectedly youthful Clov (a nice touch) is one of the finest interpretations of a Beckett role that I’ve had the privilege to see. Scarcely less convincing are Mr. Havergal and Ms. Oliver, who give the uncanny, absolutely convincing impression of having known one another for decades.

The play’s not-quite-slapstick is enacted with delicate subtlety in Ms. Perloff’s staging, and Mr. Gabriel’s stiff-legged, sweetly patient and unexpectedly youthful Clov (a nice touch) is one of the finest interpretations of a Beckett role that I’ve had the privilege to see. Scarcely less convincing are Mr. Havergal and Ms. Oliver, who give the uncanny, absolutely convincing impression of having known one another for decades.

Mr. Irwin is, of course, a great performer, but he lacks the vocal resources of a great actor, and he seems no more comfortable playing Hamm, whose name clearly indicates his profession, than he was playing the similarly verbal George in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” on Broadway. It isn’t that he misunderstands Beckett. His performance as Vladimir in the 2009 Broadway revival of “Waiting for Godot” was masterly in its underplayed simplicity. But instead of unfurling Hamm’s orotund utterances (“Can there be misery loftier than mine?”) like a ripe-voiced ham actor, he speaks them in a fussy, over-decorated manner that doesn’t quite hit the mark. What is memorable about his performance is its thwarted physicality….

“Endgame,” which runs for an hour and a half, needs no curtain raiser, but Ms. Perloff has chosen to preface it with an identically effective performance of “Play,” Beckett’s 1963 skit about a husband, a wife and the Other Woman, all of whom are seated in giant urns (only their heads are visible). Though “Endgame” comes off better when performed on its own, Anthony Fusco, René Augesen and Annie Purcell are very much in tune with the unmistakably autobiographical black comedy of “Play,” which moves at a brisk canter…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

From the “Beckett on Film” series, the 2000 film version of Endgame directed by Conor McPherson and starring Michael Gambon, David Thewlis, Charles Simon, and Jean Anderson:

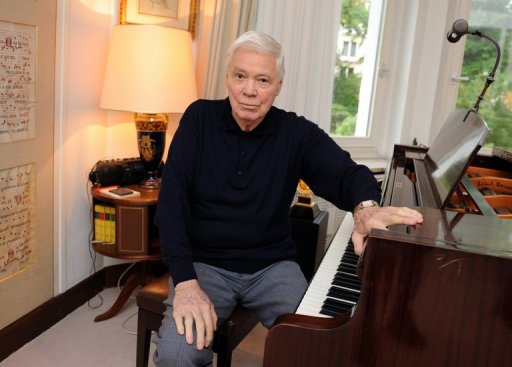

TT: A great singer—or was he?

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I consider the long and illustrious career of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The obituaries for Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who died last week at the age of 86, praised him without stint–and, for the most part, without qualification. The English tenor Ian Bostridge, who paid tribute to him in the Guardian, spoke for just about everyone when he called the German baritone “a titanic figure and a mirror of his age.” You’d never guess from reading these heartfelt paeans that Mr. Fischer-Dieskau was also one of the most controversial artists of his age, or any other….

Needless to say, no one supposes that Mr. Fischer-Dieskau was anything other than an immensely gifted and consequential musician. Though he was best known as a recitalist, he also appeared frequently in opera, and he is believed to have made more recordings than any other classical performer, including a near-complete set of Schubert’s 600 songs. He sang in the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” and performed with Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Brendel, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Vladimir Horowitz, Herbert von Karajan, Otto Klemperer, Murray Perahia, Sviatoslav Richter, George Szell and Bruno Walter, to name only a few of the giants of 20th-century music who were delighted to work with him….

Needless to say, no one supposes that Mr. Fischer-Dieskau was anything other than an immensely gifted and consequential musician. Though he was best known as a recitalist, he also appeared frequently in opera, and he is believed to have made more recordings than any other classical performer, including a near-complete set of Schubert’s 600 songs. He sang in the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” and performed with Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Brendel, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Vladimir Horowitz, Herbert von Karajan, Otto Klemperer, Murray Perahia, Sviatoslav Richter, George Szell and Bruno Walter, to name only a few of the giants of 20th-century music who were delighted to work with him….

Why, then, did so many listeners have such strong reservations about the man whom Time magazine dubbed “the world’s finest lieder singer” in 1967? Because Mr. Fischer-Dieskau’s style of singing was so individual, even idiosyncratic, that it left some people cold. Unlike the generation of recitalists that preceded him, he sang like an actor, not a storyteller. In his hands, each song became a first-person monologue, a confession of supreme intensity. Individual phrases, sometimes individual syllables, were subtly inflected so as to bring out their meaning. The effect was almost kaleidoscopic in its richness of dramatic nuance, and a listener who was used to the “simpler” style of an older singer like, say, Lotte Lehmann or Richard Tauber might easily find it over-sophisticated, even–yes–mannered.

Mr. Fischer-Dieskau’s most ardent advocates were usually more than willing to admit to certain of his other flaws. Though he sang in a half-dozen languages, he never sounded comfortable in anything other than German, just as he was never fully at ease in any music other than the Austro-German repertoire. An essentially serious personality, he was all but humorless and self-confident to the point of arrogance, two stereotypically Germanic traits that occasionally crept into his performances….

All true–yet whenever you heard him sing Franz Schubert’s “Erlkönig,” Robert Schumann’s “Mondnacht” or Hugo Wolf’s “Anakreons Grab,” to name just three of the dozens of art songs with which he was intimately identified, it was impossible, at least for the moment, to imagine anything more beautiful….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sings Schumann’s “Mondnacht” in 1974, accompanied by Wolfgang Sawallisch:

TT: Almanac

“There is but one art–to omit!”

Robert Louis Stevenson, letter to R.A.M. Stevenson (October 1883)