My brother and sister-in-law are moving into my mother’s house in Smalltown, U.S.A. It was built a half-century ago and is in need of much repair, so Dave has set about remodeling the place, starting with what used to be my bedroom. Though he undertook the task with my wholehearted approval, it was still a jolt when I stopped by the house, opened the door to my old room, and found…nothing. The bed I’d slept in, the bookshelf that once held my burgeoning library of paperbacks, the chest of drawers in which I placed my neatly folded clothes–all had vanished. Even the carpet was gone.

My brother and sister-in-law are moving into my mother’s house in Smalltown, U.S.A. It was built a half-century ago and is in need of much repair, so Dave has set about remodeling the place, starting with what used to be my bedroom. Though he undertook the task with my wholehearted approval, it was still a jolt when I stopped by the house, opened the door to my old room, and found…nothing. The bed I’d slept in, the bookshelf that once held my burgeoning library of paperbacks, the chest of drawers in which I placed my neatly folded clothes–all had vanished. Even the carpet was gone.

“Oh, my!” I cried as I gazed through the open door, startled to hear the unfamiliar sound of my voice bouncing off the freshly painted walls. I stepped inside and was no less startled by how small the room looked. Could I really have grown up in this cramped chamber? Was this the place in which I dreamed my youthful dreams of glory? It was–or, rather, it had been. Now it was an empty, memory-free space waiting to be brought to life once more.

We have it on good authority that you can’t go home again, but the fact is that I’ve been doing so ever since I moved away from Smalltown at the age of eighteen. My mother lived at 713 Hickory Drive from 1962 until last summer, when she entered a nearby nursing home, and whenever I visited her, I always stayed there.

A few years ago I blogged about how it felt to return to the bedroom of my youth:

I sit at a rickety, ink-stained card table that’s as old as I am, set up next to the bed in which I slept as a teenager. When I glance up from my iBook, I see a homemade bookshelf (my father built it) full of tattered paperbacks, a complete set of Reader’s Digest Best-Loved Books for Young Readers, and a short stack of dusty 45s by such artists as Ray Anthony, Rosemary Clooney, Billy Daniels, Vic Damone, Stan Kenton, the McGuire Sisters, and Jo Stafford. A chromolithograph of Abraham Lincoln hangs on the wall behind me. To my left is a telephone with a dial. The only modern things in sight are the laptop computer on which I’m writing these words and the iPod on which I listen to music, both of which I brought with me….

Gone, gone with the wind!

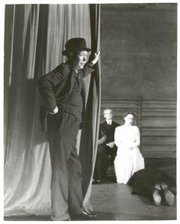

Not surprisingly, opening the door to my bare room-that-once-was put me in mind of the last act of Our Town, in which the Stage Manager permits Emily to pay a spectral visit to the Grover’s Corners of her childhood. It felt as though I had turned that scene upside down, with the Stage Manager pulling back the curtain to reveal an empty stage.

Not surprisingly, opening the door to my bare room-that-once-was put me in mind of the last act of Our Town, in which the Stage Manager permits Emily to pay a spectral visit to the Grover’s Corners of her childhood. It felt as though I had turned that scene upside down, with the Stage Manager pulling back the curtain to reveal an empty stage.

At the same time, though, I also found myself thinking of Walking Distance, the episode of The Twilight Zone in which Gig Young visits the small town where he grew up and finds that nothing–absolutely nothing–has changed. Within a few minutes he realizes that the clock has somehow been turned back, and not long after that he runs across a little boy who is himself when young. Upon meeting his father, he confesses to feeling tempted to give up on the present and spend the rest of his life in Homewood: “I’ve been living in a dead run and I was tired. And one day I knew I had to come back here. I had to get on the merry-go-round and listen to a band concert. I had to stop and breathe, and close my eyes and smell, and listen.”

Says his father:

We only get one chance. Maybe there’s only one summer to every customer. That little boy, the one I know–the one who belongs here–this is his summer, just as it was yours once. Don’t make him share it.

Those are wise words. That doesn’t make them any less bittersweet. But I felt a surge of reassurance as I looked out the window of my old bedroom and saw that the dogwood tree in my mother’s front yard had burst into blossom, as it does around this time each year. Unlike a flowering tree, a house cannot renew itself, but my brother’s decision to live in the house where we grew up is the next best thing. No, it won’t look the same–but its doors will still be open to me, and it will still be full of people whom I love.

Never mind all that. Go anyway.

Never mind all that. Go anyway.