This recording of Morten Lauridsen’s Lux Aeterna, which I mentioned in my Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column about Lauridsen, went to #9 on Amazon’s classical-music chart today. That makes me really, really happy. I love it when something I write makes a difference in the life of a first-rate artist.

This recording of Morten Lauridsen’s Lux Aeterna, which I mentioned in my Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column about Lauridsen, went to #9 on Amazon’s classical-music chart today. That makes me really, really happy. I love it when something I write makes a difference in the life of a first-rate artist.

Needless to say–I hope–I never cease to be grateful to the Journal for permitting me to use one of the world’s biggest journalistic megaphones, and trusting me to use it responsibly. On days like this, though, I’m even more grateful than usual.

Archives for January 20, 2012

GALLERY

Weegee: Naked City (Steven Kasher, 521 W. 23, up through Feb. 25). A compact and atmospheric exhibition of 125 prints by America’s greatest tabloid news photographer. Sad, sordid, appalling, and electrifyingly exciting, these hard-edged black-and-white images capture the essence of New York in the Thirties and Forties, instant by instant (TT).

TT: The edge of hopelessness

In today’s Wall Street Journal I report on a rare and important revival of The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds at Palm Beach Dramaworks. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

It’s puzzling to watch a good play fall out of fashion. Paul Zindel’s “The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds” was written in 1964, opened Off Broadway in 1970, wowed the New York critics, won a Pulitzer Prize, was turned into a movie by Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward in 1972 and looked like a deservedly sure thing in the posterity sweepstakes for many years thereafter. But while it continues to be performed by students and amateurs to this day, I’m not aware of any major professional staging that’s taken place in recent years.

Palm Beach Dramaworks’ new production of “The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds” would be worthy of note for that reason alone. Fortunately, there’s a better reason to see it: William Hayes, the company’s artistic director, has given Mr. Zindel’s play the kind of revival of which every frustrated playwright dreams, one so profoundly comprehending and persuasively acted that you’ll leave the theater wondering how “Gamma Rays” could ever have been forgotten, however briefly. Enhancing the immediacy of the staging is the troupe’s unusually shallow 218-seat theater, whose last row of seats is only 34 feet from the stage. The handsome new venue, which opened in November, manages to preserve the striking intimacy of the fast-growing company’s old 84-seat performing space.

Palm Beach Dramaworks’ new production of “The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds” would be worthy of note for that reason alone. Fortunately, there’s a better reason to see it: William Hayes, the company’s artistic director, has given Mr. Zindel’s play the kind of revival of which every frustrated playwright dreams, one so profoundly comprehending and persuasively acted that you’ll leave the theater wondering how “Gamma Rays” could ever have been forgotten, however briefly. Enhancing the immediacy of the staging is the troupe’s unusually shallow 218-seat theater, whose last row of seats is only 34 feet from the stage. The handsome new venue, which opened in November, manages to preserve the striking intimacy of the fast-growing company’s old 84-seat performing space.

At first glance there doesn’t seem to be much to “Gamma Rays.” It’s a one-set drama about the plight of a fatherless family teetering on the edge of abject poverty, a subject that has been done to death ever since “The Glass Menagerie” opened on Broadway in 1945. It has five characters, all of them women, one of whom has a bit part and one of whom never speaks, and it is dominated, as is customarily the case with such plays, by the unhappy mother, whose soul has been crushed by the struggle for survival. It is (mostly) told from the point of view of one of her children, a sensitive young girl who is clearly the author’s alter ego, and its tone alternates between delicate poetry and harsh realism.

You’ve heard it all before? Maybe–but not like this.

To be sure, Mr. Zindel’s plot is as simple as his premise. Tillie Hunsdorfer (Arielle Hoffman), the sensitive child, has been encouraged by one of her teachers to compete in a science fair, and she and Ruth (Skye Coyne), her older, epileptic sister, long desperately for Beatrice (Laura Turnbull), their mother, to come to the awards ceremony. But Beatrice, incapacitated by self-pity and drink, is no longer capable of summoning up any love for her children, and when they lose patience with her at last, she lashes out in a way that is shocking enough to make the audience gasp with horror.

Stock stuff, in other words, but Mr. Zindel has charged it with the kind of passionate feeling that can ennoble the least orginal of scripts, and no sooner does “Gamma Rays” get under way than you are drawn irresistibly into the Hunsdorfers’ unhappy lives. He also takes care to provide just enough hope to make the play bearable, though never so much as to undercut its hard-earned anguish….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

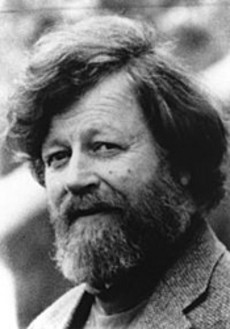

TT: The best composer you’ve never heard of

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I write about Shining Night: A Portrait of Composer Morten Lauridsen, a film documentary that will receive its first public screening next month. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

It’s been a long time since an American classical composer became famous, much less popular. Philip Glass was probably the last one whose name would become passably well known to the public at large, and even Mr. Glass isn’t nearly as famous as, say, Aaron Copland. That says a lot about the marginal place of high culture in America–none of it good.

So who ought to be famous? Or, to put it another way, who’s writing classical music these days that’s accessible enough to satisfy lay listeners, yet serious enough to impress trained musicians?

Morten Lauridsen, that’s who.

Don’t be surprised if Mr. Lauridsen’s name is unfamiliar to you. If you sing in a choir or go out of your way to listen to new choral music, there’s a better-than-even chance that you’ll have heard of him. If not, not. Though Mr. Lauridsen’s music is more widely performed than that of any other contemporary choral composer, he doesn’t get talked about on TV or written about in magazines, and highbrow music critics typically ignore his premieres. Yet he has no shortage of ardent fans, one of whom, the poet Dana Gioia, describes him as “one of the few living composers whom I would call great.”

Don’t be surprised if Mr. Lauridsen’s name is unfamiliar to you. If you sing in a choir or go out of your way to listen to new choral music, there’s a better-than-even chance that you’ll have heard of him. If not, not. Though Mr. Lauridsen’s music is more widely performed than that of any other contemporary choral composer, he doesn’t get talked about on TV or written about in magazines, and highbrow music critics typically ignore his premieres. Yet he has no shortage of ardent fans, one of whom, the poet Dana Gioia, describes him as “one of the few living composers whom I would call great.”

Mr. Gioia, the past chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, speaks these words of praise in a film documentary called “Shining Night: A Portrait of Composer Morten Lauridsen” that will receive its premiere on Feb. 7 in Palm Springs, Calif., followed by screenings in Cincinnati, New York City, San Francisco, Seattle, and other locations. The film, directed by Michael Stillwater, is a heartening rarity, a thoroughly intelligent classical-music program that strikes an appropriate balance between words and music. Most of the talking is done by Mr. Lauridsen himself and all of it is to the point, but plenty of time is devoted to the music that is the true point of “Shining Night,” and by film’s end you’ll know what it sounds like and whether you want to hear more of it–as I expect you will….

Says Mr. Lauridsen: “There are too many things out there that are away from goodness. We need to focus on those things that ennoble us, that enrich us.” The musical language in which he embodies this simple belief is conservative in the best and most creative sense of the word. His sacred music is unabashedly, even fearlessly tonal, and his chiming harmonies serve as underpinning for gently swaying melodic lines that leave no doubt of his love for medieval plainchant. Nothing about his music is “experimental”: It is direct, heartfelt and as sweetly austere as the luminous sound of church bells at night….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The trailer for Shining Night:

Stephen Cleobury and the King’s College Choir perform Morten Lauridsen’s “O magnum mysterium” in 2009:

TT: Almanac

“The musical canon is not decided by majority opinion but by enthusiasm and passion, and a work that ten people love passionately is more important than one that ten thousand do not mind hearing.”

Charles Rosen, Critical Entertainments: Music Old and New