In the last of three drama columns for this week’s Wall Street Journal, I wrap up the current Broadway season with reviews of Baby It’s You! and The People in the Picture. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Every jukebox musical rises or falls on the mass appeal of the songs out of which its score is stitched. If you don’t care for ’60s girl-group pop, then you’re likely to find “Baby It’s You!” tedious–but you’ll be more exasperated by the book, which takes a real-life story that even a Stephen Sondheim buff could love and turns it into a live-action comic strip so relentlessly simple-minded as to make “Anything Goes” look like a differential equation set to music.

“Baby It’s You!” is mostly about Florence Greenberg (Beth Leavel, who is terrific), a nice Jewish housewife from New Jersey who got tired of doing dishes and started her own record label. One day Mrs. Greenberg’s daughter (Kelli Barrett) told her about four black girls who sang together for fun at the neighborhood high school, and presto! The Shirelles were born. Likewise Scepter Records, which Ms. Greenberg turned into one of the great money-making music machines of the ’60s, thanks to her knack for knowing a hit when she heard one. Along the way she fell in love with Luther Dixon (Allan Louis), who wrote and produced most of the Shirelles’ records, and their scandalous love affair (Dixon was black) broke up Ms. Greenberg’s marriage….

Here comes the catch: Floyd Mutrux and Colin Escott, who wrote the vapid book for “Million Dollar Quartet,” have done even worse by “Baby It’s You!” Every line is as predictable as tepid canned soup. (How do we know that Mr. Greenberg is a Jew? Because he says “Oy!” a lot.) As if that weren’t bad enough, Messrs. Mutrux and Escott neglected to characterize the four Shirelles, instead turning them into a squealing quartet of interchangeable parts who exist only to sing songs, change costumes, smile and shake their collective booty….

Donna Murphy is one of the best musical-comedy actresses who ever sang a showstopper, and anything she does is worth seeing, at least while she’s onstage. That said, “The People in the Picture” is yet another addition to the seemingly endless list of Lousy Musicals of 2011, an exercise in button-pushing that takes a pair of serious subjects–Alzheimer’s disease and the Holocaust–and uses them to prove the well-known fact that even on Broadway, two wrongs don’t make a right.

The recipe for “The People in the Picture”? iTake Bubbie (Ms. Murphy), a Jewish grandmother who doesn’t get along with her divorced daughter (Nicole Parker). Add Jenny (Rachel Resheff), the perky little granddaughter to whom Bubbie is telling the story of how she once led the Warsaw Gang, a touring troupe of Polish actors who ran afoul of the Nazis. Hint at a Terrible Secret that explains why Bubbie and her daughter don’t get along. Then give Bubbie a conveniently timed case of Alzheimer’s, thus forcing her to spill the beans before it’s too late. What do you get? Two and a half hours’ worth of retchworthy glop, set to the greeting-card lyrics of Iris Rainer Dart (“It’s never been easy/It’s always been rough/I give her my life/But it’s never enough”) and the perfectly serviceable music of Mike Stoller (who is better known as the other half of Leiber & Stoller) and Artie Butler. Ms. Dart also wrote the book, about which I need say only that it actually contains the phrase “Doctor schmoctor” and a joke about Josef Mengele….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Donna Murphy sings “Loving You” in the original production of Stephen Sondheim’s Passion:

Archives for 2011

TT: High culture goes bankrupt

If you’re following ArtsJournal, you know all about the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia Orchestra, the apparent demise of the Syracuse Symphony and Seattle’s Intiman Theater, and all the other horror stories that have made April the cruelest month in recent memory for art in America. In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal, I take a look at the current situation. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

What’s the problem? In the immortal (if apocryphal) words of Sam Goldwyn, “If nobody wants to see your picture, there’s nothing you can do to stop them.” Corollary: If nobody can afford a ticket to your show, there’s nothing you can do to make them buy one. When money is tight and ticket prices keep climbing, playgoers and opera buffs will respond by staying home. Moreover, the high-culture business models of the past don’t work anymore. In particular, the subscription-based models that kept opera and theater companies and symphony orchestras afloat throughout the 20th century are no longer viable now that younger Americans are unwilling to commit in advance to attending future performances, and most of these groups are still trying to find consistently effective new ways to balance the books.

And what’s the moral of the story? Here’s part of it: High-culture unions that fight to hang on to an untenable status quo are shooting themselves in the head. Labor leaders invariably respond to managerial cries of disaster-around-the-corner by arguing that their members should not be made to suffer today for the managerial mistakes of the past. But in the end, it doesn’t matter who made the first blunder. Everybody in the culture business, union leaders included, has been guilty of chronic myopia when it comes to outmoded business models. The point is that there is no longer any alternative to root-and-branch fiscal reform. What’s more, managers and board members now know this. Increasingly, they’re willing to shut up shop altogether–or, like the Philadelphia Orchestra, declare bankruptcy–rather than purchase short-term labor peace, as they did in the past, by agreeing to contracts that they can no longer afford….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Apropos of Danse Russe (V)

The opening of the Joffrey Ballet’s reconstruction of the original 1913 Ballets Russes production of The Rite of Spring, with music by Igor Stravinsky, décor by Nicholas Roerich, and choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky. The choreography was reconstructed and staged by Millicent Hodson:

TT: Almanac

“The over-publicized bit about expression (or non-expression) was simply a way of saying that music is supra-personal and super-real and as such beyond verbal meanings and verbal descriptions. It was aimed against the notion that a piece of music is in reality a transcendental idea ‘expressed in terms of’ music, with the reductio ad absurdum implication that exact sets of correlatives must exist between a composer’s feelings and his notation. It was offhand and annoyingly incomplete, but even the stupider critics could have seen that it did not deny musical expressivity, but only the validity of a type of verbal statement about musical expressivity. I stand by the remark, incidentally, though today I would put it the other way around: music expresses itself.”

Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Expositions and Developments

TT: Song of himself

In the second of three drama columns for this week’s Wall Street Journal, I review the Broadway revival of The Normal Heart. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The way in which you respond to the Broadway revival of “The Normal Heart,” Larry Kramer’s play about the early years of the AIDS epidemic, may depend on how old you were in 1985, when it was first seen Off Broadway. Those who are too young to remember when AIDS was laying waste to a generation of gay men could well be stunned into submission by the unremitting ferocity of “The Normal Heart.” But now that AIDS has become a chronic condition rather than a death sentence, Mr. Kramer’s play must stand on its artistic merits, not its impassioned sincerity. How does it hold up? Better than I expected, but not as well as I’d hoped.

The way in which you respond to the Broadway revival of “The Normal Heart,” Larry Kramer’s play about the early years of the AIDS epidemic, may depend on how old you were in 1985, when it was first seen Off Broadway. Those who are too young to remember when AIDS was laying waste to a generation of gay men could well be stunned into submission by the unremitting ferocity of “The Normal Heart.” But now that AIDS has become a chronic condition rather than a death sentence, Mr. Kramer’s play must stand on its artistic merits, not its impassioned sincerity. How does it hold up? Better than I expected, but not as well as I’d hoped.

“The Normal Heart” is an autobiographical play whose hero, Ned Weeks (Joe Mantello), is Mr. Kramer’s fictional stand-in. Like the real Larry Kramer, Ned is a furiously angry gay writer who likes nothing better than an argument, and when his friends start to sicken and die from a mysterious ailment, he starts an organization (Gay Men’s Health Crisis, though it is never named in the play) whose purpose is to help them cope and draw attention to their plight. But Ned is so abrasive that he alienates most of his friends and colleagues, and when his lover (John Benjamin Hickey) becomes infected with the AIDS virus, the combined stress pushes him over the edge….

Too much of “The Normal Heart,” alas, is given over to speech-making, and the intimate scenes in which we see the characters living their lives rather than talking about them are so involving and persuasive that the table-pounding becomes all the more regrettable by contrast. An even bigger problem with “The Normal Heart” is that it is self-aggrandizing to an astonishing degree: Mr. Kramer portrays himself as a flawed but ultimately heroic figure, a kind of secular Moses, and the fact that he really did make a historic contribution to the fight against AIDS doesn’t make the portrayal any easier to swallow without gagging….

It helps greatly that Mr. Mantello, who is vastly better known these days as a director but who starred in the original Broadway production of “Angels in America,” is giving one of the best performances of the season, on or Off Broadway. He doesn’t do anything fancy, nor does he hungrily solicit the audience’s sympathy: Instead he plays Ned with a simplicity and straightforwardness that makes him fully understandable….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Anything Goes (musical, G/PG-13, mildly adult subject matter that will be unintelligible to children, closes Jan. 8, reviewed here)

• Born Yesterday (comedy, G/PG-13, closes July 31, reviewed here)

• The House of Blue Leaves (serious comedy, PG-13, closes July 23, reviewed here)

• How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (musical, G/PG-13, perfectly fine for children whose parents aren’t actively prudish, reviewed here)

• The Importance of Being Earnest (high comedy, G, just possible for very smart children, closes July 3, reviewed here)

• Lombardi (drama, G/PG-13, a modest amount of adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Million Dollar Quartet (jukebox musical, G, reviewed here)

• The Motherf**ker with the Hat (serious comedy, R, adult subject matter, closes June 26, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Play Dead (theatrical spook show, PG-13, utterly unsuitable for easily frightened children or adults, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN LOS ANGELES:

• God of Carnage (serious comedy, PG-13, Los Angeles remounting of Broadway production with original cast, adult subject matter, closes May 15, Broadway run reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY ON BROADWAY:

• La Cage aux Folles (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

TT: Once more unto the breach

Tonight Philadelphia’s Center City Opera Theater presents the world premiere of Danse Russe, my second operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec. The final dress rehearsal went incredibly well. Paul and I are feeling very good about everybody and everything.

Tonight Philadelphia’s Center City Opera Theater presents the world premiere of Danse Russe, my second operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec. The final dress rehearsal went incredibly well. Paul and I are feeling very good about everybody and everything.

You might enjoy reading this synopsis of the opera that I wrote for the program:

In old age, Igor Stravinsky, the greatest composer of the twentieth century, revisits the stage of the Paris theater where The Rite of Spring, the ballet score that was his youthful masterpiece, was first performed a half-century earlier, causing a riot. His memories take him back to 1913, the year when he wrote the piece. In his mind, he becomes young again and is joined on stage by Sergei Diaghilev, the ballet impresario who commissioned The Rite of Spring; Vaslav Nijinsky, who choreographed it; and Pierre Monteux, who conducted the first performance. The four men act out the events, some comical and others serious, leading up to the opening-night riot. Then Stravinsky awakes from his reverie. An old man once again, he reflects on how much the world has changed since 1913, and as the opera ends he sings with love of the “holy Russian spring” of his childhood.

That’s about the size of it.

What follows is a miniature essay about Danse Russe that Paul and I wrote yesterday. It, too, will be in the program. If you’re coming, we look forward to seeing you there. If you’d like to come but haven’t bought tickets, go here for more information.

And now…away I go!

* * *

Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was the most important piece of music written in the twentieth century, but it was also a work for the stage, and anyone who has written such a work knows that the process of moving it from the page to the stage is of necessity mad and unpredictable. That’s why Danse Russe is a comedy–what we call a “vaudeville.” It occurred to us at the outset that what Stravinsky and his collaborators went through in order to bring The Rite of Spring to fruition must have been funny, at least at times. Thus we decided to tell the story of its creation as a backstage comedy, one that makes use of the contemporary conventions of vaudeville: the dances, the jokes, the straw hats, even the pretty girl who brings in the easel cards that announce each change of scene. What we’ve written is a cross between an opera and an old-fashioned musical, and that, too, is deliberate. This is an American take on a Russian masterpiece.

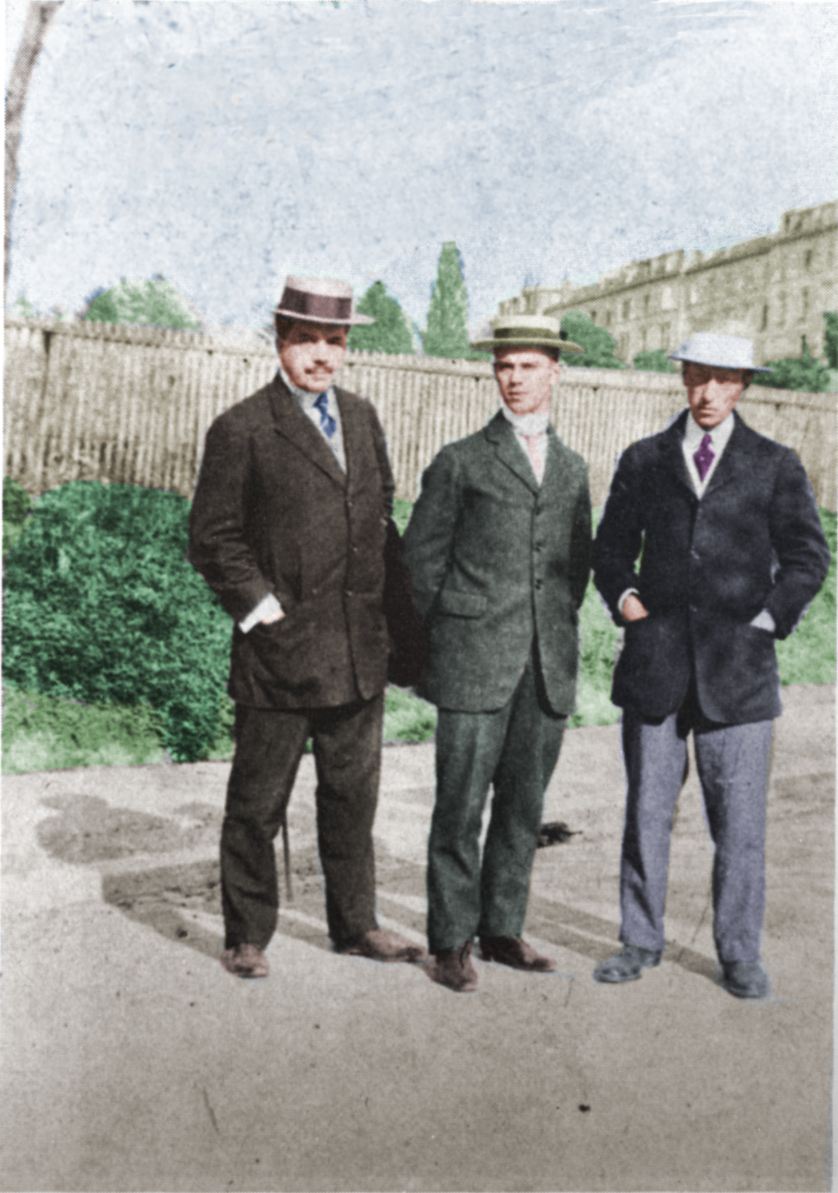

But if Danse Russe is a comedy, it is, ultimately, a serious comedy, one that seeks to offer the audience a fractured glimpse into the mysteries of the creative process. Yes, it’s a comic-book version of a celebrated moment in cultural history, but much of what you’ll be seeing is deeply informed by the historical record of the events leading up to the riotous 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring. The words that are sung and spoken by Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, Vaslav Nijinsky and Pierre Monteux in Danse Russe are in many cases based on things that they actually said or wrote in real life. Only the tone has been changed.

Howard Hawks, the director of such classic screwball comedies as Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday, liked to say that “the only difference between comedy and tragedy is point of view.” Though our point of view on the making of The Rite of Spring is comic, we know that it was very serious business indeed, and so we’ve sought to portray it with love and understanding–and a smile.

TT: Apropos of Danse Russe (IV)

Igor Stravinsky talks about his collaboration with Sergei Diaghilev and Vaslav Nijinsky and the first performance of The Rite of Spring. Also seen is Robert Craft, Stravinsky’s assistant and amanuensis. Toward the end of this clip from Stravinsky, a 1965 TV documentary, we see the composer in the Paris theater where The Rite of Spring was premiered.

In this clip, Stravinsky revisits the studio where he composed The Rite of Spring and is briefly seen conducting the score:

Stravinsky, Diaghilev, and Nijinsky are characters in Danse Russe. I used these two clips as source material for the libretto.