Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten perform Schubert’s “Mein,” from Die schöne Müllerin:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

Archives for 2011

TT: Almanac

“I think greatness happens accidentally–that sometimes one can write a little tiny piece for children or for brass band or something like that, and it may quite easily turn out to be much more important for posterity–if one can worry about posterity–than anyone’s symphonies in B flat minor. I think Schoenberg himself said that you can’t save the world with every Adagio.”

Benjamin Britten (interview, CBC, Nov. 21, 1961)

TT: Almanac

“Music demands more from a listener than simply the possession of a tape-machine or a transistor radio. It demands some preparation, some effort, a journey to a special place, saving up for a ticket, some homework on the programme perhaps, some clarification of the ears and sharpening of the instincts. It demands as much effort on the listener’s part as the other two corners of the triangle, this holy triangle of composer, performer and listener.”

Benjamin Britten, On Receiving the First Aspen Award

TT: Pops in a box

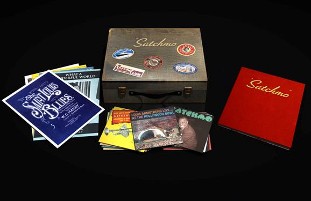

Satchmo: Louis Armstrong, the Ambassador of Jazz, out on August 9 from Universal, is an elaborately packaged box set that contains seven CDs’ worth of classic Armstrong recordings, three bonus discs, a two-hundred-page hardcover book, and various other souvenir-type items. According to Russ Titelman, the producer, Satchmo purports to be “the definitive version of the Armstrong legacy.” This is, of course, nonsense. Still, it’s certainly possible, at least in theory, to convey a reasonably complete sense of what Armstrong was all about within the compass of a seven-disc set.

Does Satchmo get the job done? I haven’t seen it yet, and nobody at Universal asked for my advice, but I have seen a complete track listing, and I can tell you that of the thirty “key recordings by Louis Armstrong” listed in the appendix to Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, twenty-seven will be included on Satchmo. That’s a damned good batting average–which figures, since Armstrong scholar–blogger Ricky Riccardi was mainly responsible for selecting the tracks.

Does Satchmo get the job done? I haven’t seen it yet, and nobody at Universal asked for my advice, but I have seen a complete track listing, and I can tell you that of the thirty “key recordings by Louis Armstrong” listed in the appendix to Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, twenty-seven will be included on Satchmo. That’s a damned good batting average–which figures, since Armstrong scholar–blogger Ricky Riccardi was mainly responsible for selecting the tracks.

For me, the only jaw-dropping omission was “Beau Koo Jack,” though it’s certainly not one of Armstrong’s most famous recordings, nor is it included in my appendix. In addition, there’s nothing from the justly celebrated album that Armstrong made with Duke Ellington in 1962. (Alas, Universal doesn’t control the rights to that album.) Otherwise, virtually all of the really important sides are present and accounted for, and plenty more besides.

I don’t know who’s going to buy Satchmo, nor do I think there’s much point in purchasing such a megadeluxe package when you can acquire all of Armstrong’s greatest recordings separately at very reasonable prices (or download them from iTunes). Still, my preliminary impression is that if you’re interested, this set appears to be an excellent piece of work.

* * *

Here’s a promotional video for Satchmo, which includes a tour of the Louis Armstrong House Museum in Queens. It’s worth watching:

TT: Almanac

“All of us–the public, critics, and composers themselves–spend far too much time worrying about whether a work is a shattering masterpiece. Let us not be so self-conscious. Maybe in thirty years’ time very few works that are well known today will still be played, but does that matter so much? Surely out of the works that are written some good will come, even if it is not now; and these will lead on to people who are better than ourselves.”

Benjamin Britten, interviewed by Edmund Tracey (Sadler’s Wells Magazine, Autumn 1966)

TT: A stage for all seasons

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Lincoln Center Festival staging of As You Like It and another production in Cape May, New Jersey, Cape May Stage’s version of Theresa Rebeck’s The Understudy. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The real star of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of “As You Like It” is the stage. In order to perform five Shakespeare plays as part of this summer’s Lincoln Center Festival, the RSC has built a replica of the 965-seat Elizabethan-style open-stage auditorium of its Courtyard Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and installed it inside the Park Avenue Armory. That’s quite a trick–but it’s not a stunt. The 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall is one of the biggest unobstructed interior spaces in Manhattan, and the only such place where it’s feasible to mount a six-week repertory season. What’s more, the hall is large enough to be naturally resonant. You can hear the actors reveling in the acoustic “bloom” that envelops their voices–and because the audience is wrapped around three sides of the stage, the sight lines are perfect….

The real star of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of “As You Like It” is the stage. In order to perform five Shakespeare plays as part of this summer’s Lincoln Center Festival, the RSC has built a replica of the 965-seat Elizabethan-style open-stage auditorium of its Courtyard Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and installed it inside the Park Avenue Armory. That’s quite a trick–but it’s not a stunt. The 55,000-square-foot Wade Thompson Drill Hall is one of the biggest unobstructed interior spaces in Manhattan, and the only such place where it’s feasible to mount a six-week repertory season. What’s more, the hall is large enough to be naturally resonant. You can hear the actors reveling in the acoustic “bloom” that envelops their voices–and because the audience is wrapped around three sides of the stage, the sight lines are perfect….

As for the production itself, it’s solidly made and frequently inspired, though the first half is straightforward to the point of occasional baldness. Michael Boyd, the company’s artistic director, has eschewed high concepts and given us a more or less traditional “As You Like It,” the theatrical equivalent of a warm, crusty loaf spread with the very best butter….

If you live in New York and don’t see shows elsewhere, then the RSC’s visit is by definition a big deal. But while “As You Like It” is really, really good, all you have to do to see something just as good is get out of town–or live somewhere else….

When I first saw “The Understudy,” I was struck by how the frenetic zaniness of the first half suddenly gave way to an unexpectedly serious group portrait of disappointment and disillusion. Even though both halves worked, they didn’t seem to fit together. But this production, ably directed by Roy Steinberg and very well acted by G.R. Johnson, Luke Darnell and Kristen Calgaro, makes a different impression, perhaps because Mr. Steinberg’s cast plays the first half of “The Understudy” more for truth than for laughs. While the Cape May Stage version isn’t as obviously funny as the Roundabout Theatre Company’s 2009 production, the transition to the second half of the play is smooth and seamless, resulting in a show that makes better emotional sense….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“The fact is, though nobody has perceived it, that a professional play-critic is a monstrosity–a sow with five legs or a man with four thumbs. Nature did not intend him, and that is why we have to conceal our repulsion when he confronts us. A keen playgoer may see, perhaps, ten, fifteen, or even twenty plays a year, and it is for him that dramatists write and that managers dangle their bait. Your newspaper-critic may see a hundred productions in a year. The result is–let me put it with unmistakable simplicity–that he does not see any play as a normal citizen would see it. He is therefore as fantastic a freak as the Yorkshireman who ate half a dozen ordinary breakfasts. However, I must give you an example of my contention. Some years ago I glanced at a play-notice by X.Y.Z., whose conceit would be pathetic if it were tolerable, and in his notice he wrote, ‘Then the usual quartet of lawn-tennis players came on, with the usual racquets,’ and, we deduce, immediately bored X.Y.Z. Not until I had read these words did I realise, being only an average playgoer, that several playwrights must have recently used the convenient device of a tennis-party for getting their characters on and off the stage. Does not this example demonstrate in a twinkling that X.Y.Z. may black-mark a play for some effect which will seem to me and you unobjectionable and even adroit? He sees too many plays, eats too many breakfasts, is a monster.”

Clifford Bax (quoted in James Agate, Ego 8)

TT: Anecdotage

This is my all-time favorite George Cukor story. It comes from No Minor Chords, André Previn’s autobiography. I hope it’s true!

* * *

While George was in the Army during the war, he was assigned to the Signal Corps Movie Unit, which was run by Frank Capra. One day he was called to Capra’s office on Long Island.

“Get a cameraman and an editor, and go to the Pentagon. General Patton is back from Europe and he’d like to make a filmed statement in his office.” George duly took off for Washington, D.C., with two cohorts. At the Pentagon they were told to se up the camera and the lights in the general’s office and wait for his imminent return. Cukor took a disbelieving look around the stark quarters.

“Get a cameraman and an editor, and go to the Pentagon. General Patton is back from Europe and he’d like to make a filmed statement in his office.” George duly took off for Washington, D.C., with two cohorts. At the Pentagon they were told to se up the camera and the lights in the general’s office and wait for his imminent return. Cukor took a disbelieving look around the stark quarters.

“Good Lord,” he said, his sophisticated taste affronted, “crossed swords behind the desk! How on the nose can we get? Let’s take them down, move the desk in front of the window, and see if we can get a better chair.” His two co-workers were apprehensive. Patton was a man who wore a steel helmet at all times, carried a revolver, and was not given to a lot of patience. But George was not to be swayed; after all, he was back in his element, he was directing film, and the fact that he was a buck private about to deal with the scourge of Rommel did not enter his mind. The swords were taken down and the desk was in mid-move when Patton flung open the door and walked in. His rage was instant and fearful. He screamed at the top of his voice, “What do you think you’re doing, you unspeakable Hollywood bastards!” This was only the beginning of a flow of invective of which Blackbeard the Pirate would have been proud.

George sighed deeply with resignation. He was not at all frightened. Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo–he had dealt with tantrums all his life. He walked over to the general, who was now nearing the fortissimo apex of his wrath, and put his arm around the shoulder with the four stars on it. “Now, General,” he said, soft-voiced and persuasive, “are we going to be silly about this?”

The cameraman and the editor blanched. Visions of firing squads or guillotines danced in front of them. Patton stopped in mid-threat. Never had he heard a sentence remotely like the one this private had just uttered. The insanity of the moment got to him, and he laughed and laughed. The swords were put back, the newsreel was filmed, and George Cukor went back to the Signal Corps base, innocent of the dire consequences his friends had deemed inevitable.