“If you say that two sheep added to two sheep make four sheep, your audience will accept it patiently–like sheep. But if you say it of two monkeys, or two kangaroos, or two sea-green griffins, people will refuse to believe that two and two make four. They seem to imagine that you must have made up the arithmetic, just as you have made up the illustration of the arithmetic. And though they would actually know that what you say is sense, if they thought about it sensibly, they cannot believe that anything decorated by an incidental joke can be sensible. Perhaps it explains why so many successful men are so dull–or why so many dull men are successful.”

G.K. Chesterton, Autobiography

Archives for December 2011

TT: Stocking stuffers for the hopelessly arty

On Friday The Wall Street Journal will be publishing my best-theater-of-the-year list for 2011. Hence I thought that this would be a good time for me to take a quick look back at my ten favorite Top Five picks of the year just past:

• Debra Bricker Balken, John Marin: Modernism at Midcentury (Yale, $40). The catalogue of the Portland Museum’s superlative exhibition of Marin’s late paintings and watercolors is itself a first-class effort, a penetrating study of a great painter whose work is no longer widely known save to students of American modernism.

• Debra Bricker Balken, John Marin: Modernism at Midcentury (Yale, $40). The catalogue of the Portland Museum’s superlative exhibition of Marin’s late paintings and watercolors is itself a first-class effort, a penetrating study of a great painter whose work is no longer widely known save to students of American modernism.

• Car 54 Where Are You?: Complete First Season (Shanachie, four DVDs). All thirty episodes of the 1961-62 season of one of the most clever and well-made situation comedies ever to appear on American television. Nat Hiken, who made Phil Silvers a TV star, did the same for Fred Gwynne and Joe E. Ross in this zany portrait of a squad-car team who troll the Bronx in search of trouble–all of which happens to them. An absolute must for golden-age TV buffs.

• The Essential Rosanne Cash (Sony Legacy, two CDs). Thirty-six tracks from one of America’s most creative singer-songwriters, chosen by Cash herself. An ideal one-stop introduction to her work, especially when heard in tandem with Composed, Cash’s 2010 memoir.

• John Gielgud, Ages of Man (Entertainment One). Courtesy of the Archive of American Television, the 1966 broadcast version of the great actor’s one-man Shakespeare show, which aired on CBS on two consecutive Sunday afternoons (the network suits didn’t think anybody would sit still long enough to watch the whole show in one go) and has been in limbo ever since. Contemporary Shakespeare style has changed beyond recognition since Gielgud’s day, but his elegant delivery and exquisitely modulated voice remain as seductive–and intelligent–as ever.

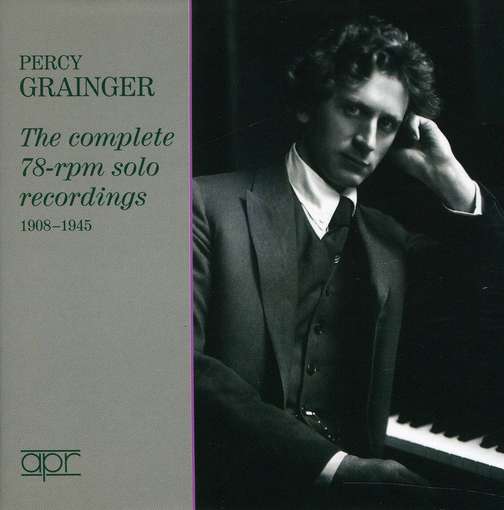

• Percy Grainger, The Complete 78-RPM Solo Recordings 1908-1945 (Appian, five CDs). The composer of “Country Gardens” and “Molly on the Shore” was also one of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century, a marvelously idiosyncratic virtuoso whose style ranged from tender lyricism to explosive extroversion. Most of his 78s have been unavailable in any format since their original release. This much-needed box set solves that problem–and does it right. Ward Marston’s digital transfers of such classic Grainger recordings as Chopin’s B Minor Sonata, Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, and Grieg’s “Wedding Day at Troldhaugen” are crystal-clear and scratch-free.

• Percy Grainger, The Complete 78-RPM Solo Recordings 1908-1945 (Appian, five CDs). The composer of “Country Gardens” and “Molly on the Shore” was also one of the greatest pianists of the twentieth century, a marvelously idiosyncratic virtuoso whose style ranged from tender lyricism to explosive extroversion. Most of his 78s have been unavailable in any format since their original release. This much-needed box set solves that problem–and does it right. Ward Marston’s digital transfers of such classic Grainger recordings as Chopin’s B Minor Sonata, Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, and Grieg’s “Wedding Day at Troldhaugen” are crystal-clear and scratch-free.

• Justified: The Complete First Season (Sony, three DVDs). In this cable-TV series, Graham Yost takes U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens, one of Elmore Leonard’s most attractive recurring characters, and returns him to Kentucky’s Harlan County for a series of freshly written adventures that have the true Leonard touch. Timothy Olyphant, who plays Givens, is exactly, exquisitely right.

• Pat Metheny, What’s It All About (Nonesuch). A lovely sequel to One Quiet Night, Metheny’s 2009 album of acoustic-guitar solos. This time around the fare consists of pop standards, some likely (“Alfie”), others joltingly unexpected (“Betcha by Golly, Wow”), and all played with luminescent sensitivity. Ideal for wee-small-hours listening.

• A Minister’s Wife (PS Classics). The original-cast recording of the Lincoln Center Theatre production of this musical version of George Bernard Shaw’s Candida is a major event. I called it “the most important new musical since The Light in the Piazza” when I reviewed the show in The Wall Street Journal, and now you can revel at leisure in Joshua Schmidt’s astringent yet tuneful score. If you didn’t see A Minister’s Wife on stage, make haste to hear it on record.

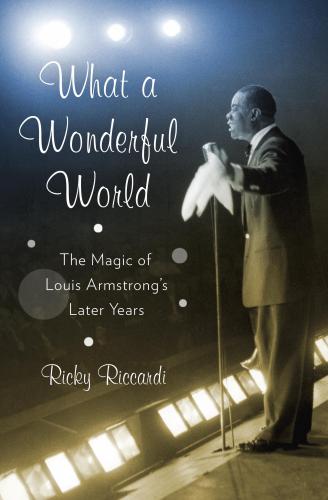

• Ricky Riccardi, What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years (Pantheon, $28.95). I can’t do any better than to repeat my dust-jacket blurb: “The later years of Louis Armstrong are one of the most fascinating untold tales in the history of jazz. What a Wonderful World is indispensable to anyone with a serious interest in the greatest jazz musician of the twentieth century.” If you liked Pops, you need to read this book.

• Ricky Riccardi, What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years (Pantheon, $28.95). I can’t do any better than to repeat my dust-jacket blurb: “The later years of Louis Armstrong are one of the most fascinating untold tales in the history of jazz. What a Wonderful World is indispensable to anyone with a serious interest in the greatest jazz musician of the twentieth century.” If you liked Pops, you need to read this book.

• Wesley Stace, Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer (Picador, $15 paper). A bewitchingly clever historical thriller in which the lives and work of Peter Warlock, Constant Lambert, and Carlo Gesualdo are blended into the hair-raising tale of an unworldly music critic who writes an opera libretto for a flint-hearted composer who returns the favor in the most malevolent way imaginable. The author (better known in pop-music circles as John Wesley Harding) has done a virtuosic job of fusing fact with fiction, and the result is one of the few novels with a musical setting in which the background is rendered accurately. Absolutely not for musicians only, though those who already know the dramatis personae will be dazzled by the sure-footed skill with which Stace has put their real-life stories to novelistic use.

TT: Just because

James Taylor sings “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“They who lack talent expect things to happen without effort. They ascribe failure to a lack of inspiration or ability, or to misfortune, rather than to insufficient application. At the core of every true talent there is an awareness of the difficulties inherent in any achievement, and the confidence that by persistence and patience something worthwhile will be realized. Thus talent is a species of vigor.”

Eric Hoffer, Reflections on the Human Condition

TT: For the record

I had lunch with Christopher Hitchens in 2000 at the behest of a mutual friend, and didn’t like him at all. Though he was perfectly nice to me, Hitchens struck me as snobbish and vain, the very model of an expatriate Brit frolicking among the ugly Americans at whom he delighted to sneer. We never met again.

Two years later, he gave my biography of H.L. Mencken an indifferent review in the New York Times. It may or may not have prejudiced me against his essays, which too often struck me as self-consciously contrarian rather than expressive of deep-seated convictions, of which I frankly doubt he had all that many.

I did, however, greatly admire (as who did not?) the courage with which he faced his fast-approaching end, as well as the stylish eloquence with which he described it in print. We should all be so brave–and so honest.

Ave atque vale.

UPDATE: In case you weren’t reading this blog in 2005, here‘s something I wrote back then about speaking ill of the recently dead. As you can see, I haven’t changed my mind–and Hitchens would have agreed with me.

TT: A master’s music

Here are five Bob Brookmeyer CDs of which I’m especially fond:

• Bob Brookmeyer Quintet, Traditionalism Revisited, with Jimmy Giuffre and Jim Hall (1957)

• Bob Brookmeyer Quintet, Traditionalism Revisited, with Jimmy Giuffre and Jim Hall (1957)

• The Bob Brookmeyer Small Band, Live at Sandy’s Jazz Revival (1978)

• The Bob Brookmeyer New Art Orchestra, New Works: Celebration (1999)

• Holiday: Bob Brookmeyer Plays Piano (2001)

• The Bob Brookmeyer New Art Orchestra, Get Well Soon (2004)

TT: Bob Brookmeyer, R.I.P.

Nothing you can say about Bob Brookmeyer can possibly rival the truth about him. He was one of the giants of jazz, a great valve trombonist, a composer of the first rank, and an astonishingly gifted teacher whose pupils included Maria Schneider. He was also a man of ear-shattering candor who liked nothing better than saying whatever was on his mind at any given moment, especially when he knew it would give offense. Unlikely as it may sound, he was genuinely lovable–unless you happened to be on the receiving end of one of his diatribes, and sometimes even then–and I adored him.

Nothing you can say about Bob Brookmeyer can possibly rival the truth about him. He was one of the giants of jazz, a great valve trombonist, a composer of the first rank, and an astonishingly gifted teacher whose pupils included Maria Schneider. He was also a man of ear-shattering candor who liked nothing better than saying whatever was on his mind at any given moment, especially when he knew it would give offense. Unlikely as it may sound, he was genuinely lovable–unless you happened to be on the receiving end of one of his diatribes, and sometimes even then–and I adored him.

I met Bob when I interviewed him in 1999 for a profile that appeared in the Sunday New York Times on the occasion of his seventieth birthday:

Today is the jazz trombonist Bob Brookmeyer’s 70th birthday, and he’s surprised. He never expected to outlive such illustrious colleagues as Al Cohn, Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan and Zoot Sims, with whom he worked back in the days when he was doing his best to drink himself to death. “I didn’t think I’d see 30,” he said in the matter-of-fact tones of a man whose memories were horrendous enough to need no embroidery. “I almost didn’t make 45. My major accomplishment back then was not falling down more than, oh, 10 times a day.”

He was amused by what I wrote, and a friendship resulted. We didn’t see much of one another–he stayed as far away from Manhattan as he could–but our rare meetings were full of raucous laughter and much affection. Alas, what would have been our last meeting failed to take place because of the illness that claimed his life last night. He was too depressed to want to be seen, and I was too shy to insist on seeing him.

Now he is gone, but his music will always be with us, for which much thanks.

TT: (Still)born again

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column, I sound the alarm about On a Clear Day You Can See Forever and Lysistrata Jones. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

In the rogues’ gallery of problem musicals, “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever” ranks right next to “Candide” and “Merrily We Roll Along” at the very top of the list. The Burton Lane-Alan Jay Lerner score is so good that everyone who loves musical comedy dreams of seeing the show successfully revived, but Lerner’s book is so bad that no one has ever figured out how to do it. Now Michael Mayer, the director of “American Idiot” and “Spring Awakening,” has taken a costly shot at what most theater buffs have long thought impossible–and proved them right.

The original “On a Clear Day” was the muddled story of Mark Bruckner, a Manhattan psychiatrist who hypnotizes a ditsy young client named Daisy and discovers that she appears to be the reincarnation of one Melinda Wells, an 18th-century society lady from London, with whom he thereupon falls in love. Daisy/Melinda was the star of the show–Barbara Harris played her on Broadway in 1965, Barbra Streisand in the even more confusing 1970 film version–and nobody got the girl(s). In the new “On a Clear Day,” whose book, written by Peter Parnell, retains recognizable chunks of Lerner’s 1965 script but has mostly been written from scratch, the shrink (Harry Connick, Jr.) is the star and his ditsy young client becomes a ditsy gay florist (David Turner) who appears to be the reincarnation of a beautiful swing-era big-band canary (Jessie Mueller).

The original “On a Clear Day” was the muddled story of Mark Bruckner, a Manhattan psychiatrist who hypnotizes a ditsy young client named Daisy and discovers that she appears to be the reincarnation of one Melinda Wells, an 18th-century society lady from London, with whom he thereupon falls in love. Daisy/Melinda was the star of the show–Barbara Harris played her on Broadway in 1965, Barbra Streisand in the even more confusing 1970 film version–and nobody got the girl(s). In the new “On a Clear Day,” whose book, written by Peter Parnell, retains recognizable chunks of Lerner’s 1965 script but has mostly been written from scratch, the shrink (Harry Connick, Jr.) is the star and his ditsy young client becomes a ditsy gay florist (David Turner) who appears to be the reincarnation of a beautiful swing-era big-band canary (Jessie Mueller).

Mr. Mayer is responsible for dreaming up this silly-sounding premise, and while I suppose it would be wrong to say that nobody in the world could ever have made it work onstage, he and Mr. Parnell have definitely failed to do the job….

Mr. Connick is, of course, a popular school-of-Sinatra swing balladeer who made a splash in the 2006 Broadway revival of “The Pajama Game.” His acting skills, however, are strictly limited, and whoever thought he was up to playing a Jewish shrink ought to have his head examined, preferably with a blunt instrument….

Douglas Carter Beane’s brand of flyweight camp is not to all tastes, but plenty of people flipped over “Xanadu,” and those unpicky folk are more than welcome to revel in “Lysistrata Jones,” in which Aristophanes’ classic comedy is turned into a spoofy-woofy college musical about an inept basketball team whose players are galvanized into action when their girlfriends vow not to sleep with them until they win a game. In the ever-relevant words of Max Beerbohm, “For people who like that kind of thing, that is the kind of thing they like.”

If you’re that kind of person, be forewarned that Mr. Beane’s book is vapid to the max and Lewis Flinn’s score is as tuneful as a ringtone medley….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.