“She had seen death at work, its industrious regard for detail, and, like the men who dug up the roads, its preference for doing the job slowly.”

William Brodrick, The Sixth Lamentation

Archives for October 2011

TT: Norman Corwin, R.I.P.

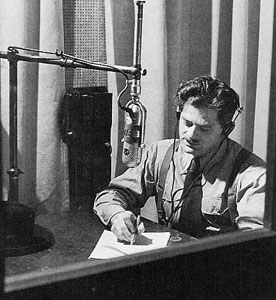

Norman Corwin, who wrote verse dramas for network radio back in the days when such things were possible, has died at the age of 101. I had the great good fortune to interview him in 1996, and wrote about the experience in a column for Civilization that I subsequently posted on this blog:

Norman Corwin, who wrote verse dramas for network radio back in the days when such things were possible, has died at the age of 101. I had the great good fortune to interview him in 1996, and wrote about the experience in a column for Civilization that I subsequently posted on this blog:

This is how important Norman Corwin was: nine months before World War II ended, CBS commissioned him to write an original radio play to be broadcast on V-E Day. It was called On a Note of Triumph, and it made so powerful an impact that more than a few of its first listeners still remember parts of it word for word. “I’m going to interview Norman Corwin this morning,” I told an older friend of mine, who promptly rattled off its opening lines: Take a bow, G.I.,/Take a bow, little guy./The superman of tomorrow lies at the feet of you common men of this afternoon.

There was room on commercial radio for things like that, just as there was room for Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony, or Orson Welles directing Shakespeare. But it couldn’t last, and it didn’t. One day in 1948, Corwin ran into Bill Paley, the president of CBS, on a train from Pasadena to New York. “We’ve simply got to face up to the fact that we’re a commercial business,” Paley told his star playwright. “If we do not reach as many people as possible, then we’re not making the best use of our talent, our time, and our equipment.” At that moment, Corwin knew his own days at CBS were numbered. To make matters worse, 1948 was also the year network TV finally arrived, and it wasn’t long before radio itself was on the ropes, laid low by Milton Berle. To be sure, Corwin didn’t want for work after he left CBS–among other things, he wrote the script for Lust for Life, Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 film version of the life of Vincent Van Gogh–but the thing he loved best was a thing of the past….

Read the whole thing here.

* * *

The Los Angeles Times obituary is here.

To listen to the 1945 CBS broadcast of On a Note of Triumph, starring Martin Gabel and scored by Bernard Herrmann, go here.

To listen to Corwin’s The Plot to Overthrow Christmas, as rebroadcast by CBS in 1942, go here.

My Wall Street Journal review of the Irish Repertory Theatre’s 2009 off-Broadway revival of The Rivalry, Corwin’s 1959 play about the Lincoln-Douglas debates, is here.

My 2006 “Sightings” column about Lust for Life is here.

Norman Corwin talks about writing On a Note of Triumph:

TT: Snapshot

Luciana Souza records her setting of Pablo Neruda’s “Sonnet 49” in 2003:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“The incredible has a habit of disrupting the parts of our lives to which we’re most attached.”

William Brodrick, The Sixth Lamentation

TT: Time present and time past

I spend so much time seeing plays and musicals these days that I don’t get to spend nearly enough time doing anything else. When I went to the Blue Note on Sunday night to hear Pat Metheny and Larry Grenadier, I realized with a start that I couldn’t remember the last time I’d been to a nightclub. Such is the paradoxical fate of the erstwhile generalist who mutates into a specialist in midlife: it’s immeasurably rewarding to immerse yourself in a single discipline, but it cuts you off from all sorts of other good things.

I spend so much time seeing plays and musicals these days that I don’t get to spend nearly enough time doing anything else. When I went to the Blue Note on Sunday night to hear Pat Metheny and Larry Grenadier, I realized with a start that I couldn’t remember the last time I’d been to a nightclub. Such is the paradoxical fate of the erstwhile generalist who mutates into a specialist in midlife: it’s immeasurably rewarding to immerse yourself in a single discipline, but it cuts you off from all sorts of other good things.

Fortunately, I bobbed to the surface in exactly the right place at exactly the right time, for Metheny and Grenadier gave the kind of performance that you’re lucky to see a half-dozen times in your life, totally focused and hypnotically involving. It was ecstasy-making to watch them move with nonchalant grace from “Bright Size Life,” the song in which Metheny helped codify the language of fusion thirty-seven years ago, to an oblique, near-abstract, hard-swinging blues, sounding equally at ease in both tunes.

I had the good luck to be seated ten feet from the bandstand, and to be sitting with Julia Dollison and Kerry Marsh, two old friends who are themselves jazz musicians of the highest accomplishment. (I wrote the liner notes for Julia’s first album, which was co-produced by Kerry, her husband.) All three of us know Pat a bit, and we got a chance to chat with him after the show, which was almost as much fun as hearing him play. He is the nicest and most modest fellow imaginable–you’d never guess that he’s also one of the most important and influential jazz guitarists of the postwar era–and it was pure pleasure to catch up and swap stories.

Listening to Sunday’s performance had a stirring effect on me. As I said to Julia and Kerry afterward, “That wasn’t a set–it was a way of life.” For me, of course, it was a reminder of the way of life that I practiced many years ago, and to which my friends have consecrated their own lives. I like to call myself a recovering musician, a line that rarely fails to get a laugh, perhaps because there’s a certain amount of truth in it. I wrote about that in this space five years ago:

Listening to Sunday’s performance had a stirring effect on me. As I said to Julia and Kerry afterward, “That wasn’t a set–it was a way of life.” For me, of course, it was a reminder of the way of life that I practiced many years ago, and to which my friends have consecrated their own lives. I like to call myself a recovering musician, a line that rarely fails to get a laugh, perhaps because there’s a certain amount of truth in it. I wrote about that in this space five years ago:

Somebody asked me once if I were a frustrated musician. “No,” I said, “I’m a fulfilled writer.” But that doesn’t mean I never think about what might have been, much less what used to be. The way I feel about having once been a musician is not unlike the way some reformed alcoholics feel about booze. They know they can’t live with it anymore, but they also know how much they liked it, and they remember, as clearly as if it were this morning, how good that last drink tasted. I remember, too.

Needless to say, my playing days are over. I’m a full-time writer now, for better or worse, and I feel even more fulfilled now that my professional life encompasses both criticism and writing for the stage. Nor do I regret having chosen to fling myself into the world of theater, whose endless bounty feeds my soul far more than adequately. But as I packed my bag and prepared to fly to San Francisco, where I’ll be seeing Kevin Spacey in Richard III tomorrow night, I found myself feeling no less grateful for having had the chance to dip my toe into the once-familiar stream of jazz again, if only for a night. It was good to be home.

* * *

Bill Evans plays “Time Remembered”:

TT: Fascist thugs and useful idiots

In light of the recent death of Steve Jobs, The Wall Street Journal has given me an extra drama column today in which to review Mike Daisey’s The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Mike Daisey is the inventor of his own pigeonhole. He calls himself a “storyteller” and specializes in semi-improvised autobiographical monologues of the kind that made Spalding Gray semi-famous. But his “stories” tend to be issue-driven and to have a political edge, which makes them seem more like theatrical journalism than storytelling. In “The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs,” Mr. Daisey’s journalistic side comes to the fore, in part because he had the luck (if that’s the word) to bring his new show to the Public Theater immediately after the death of its subject. Even if Mr. Jobs were still alive, this show, in which Mr. Daisey weaves together his experience as a technogeek with the story of a visit that he paid to the Chinese factories in which Apple’s products are assembled, would still have a journalistic feel.

All that said, Mr. Daisey’s new monologue is first and foremost a work of theatrical art, just as Mr. Daisey himself, though he is not an actor in the ordinary sense of the word, is an awesomely gifted stage performer. Indeed, it is so strong a piece of theater that you can’t help but wonder about its journalistic soundness. About that I’m not qualified to render judgment, but I can vouch for its theatrical soundness: “The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs” ranks alongside “Follies” as the most exciting show in town.

Mr. Daisey used to worship at the Apple altar, and Mr. Jobs, he claims, was “the only hero I ever had.” Then he went to Shenzhen, the city where Apple products are put together in huge sweatshop-like factories that reportedly make use of child labor. Mr. Daisey claims to have talked his way into some of these factories, and to have spoken to some of the leaders of the illegal “secret unions” that are struggling to improve conditions in Shenzhen. What he saw shocked him to the core…

Mr. Daisey used to worship at the Apple altar, and Mr. Jobs, he claims, was “the only hero I ever had.” Then he went to Shenzhen, the city where Apple products are put together in huge sweatshop-like factories that reportedly make use of child labor. Mr. Daisey claims to have talked his way into some of these factories, and to have spoken to some of the leaders of the illegal “secret unions” that are struggling to improve conditions in Shenzhen. What he saw shocked him to the core…

Mr. Daisey is the least glamorous figure imaginable, a sweaty, bulbous fellow with a foot-wide mouth whose demeanor suggests the kind of smart-ass second banana you might expect to encounter in a high-school romcom. But no sooner do the proceedings get underway than he starts to work his coarsely irresistible magic. Imagine an essay by Tom Wolfe being read out loud by John Belushi and you’ll get some idea of how he comes across onstage. His klaxon-horn delivery is that of a stand-up comedian, but it acquires an energizing tightness of focus from the fact that he remains seated throughout the show, using his hands like a mime to add color to his words….

The trouble with “The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs,” as with all theatrical journalism, is that Mr. Daisey is in essence asking us to take his word for it. He hasn’t brought back pictures or named names, and the artful anger with which he tells his tale inevitably makes it still more suspect. You don’t have to be a puritan to prefer that facts be served straight up. Still, Mr. Daisey deserves much credit for telling his audience things it almost certainly doesn’t want to hear…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“She smiled, as only the very old can, intimating an acceptance of things that once could not be accepted.”

William Brodrick, The Sixth Lamentation

TT: Time off (and on)

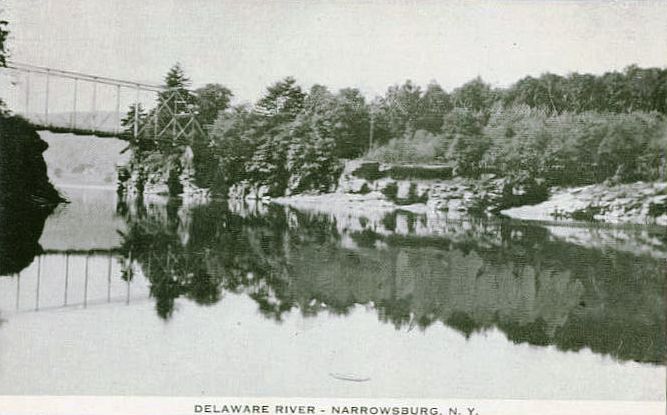

I didn’t take any time off this summer, so last week I compensated myself for my excessive industry by spending three nights with Mrs. T at Ecce Bed and Breakfast, the peaceful retreat in the southern Catskills where we spent part of our honeymoon four years ago and about which I’ve written more than once in this space. Since the point of taking time off is to do nothing, I don’t have any leisurely activities to describe. We slept late, we took a long afternoon drive and looked at the autumn foliage, we sat on the terrace and looked at the Upper Delaware River, we ate a very nice dinner in the quaint little town of Narrowsburg, and we watched a couple of movies.

I didn’t take any time off this summer, so last week I compensated myself for my excessive industry by spending three nights with Mrs. T at Ecce Bed and Breakfast, the peaceful retreat in the southern Catskills where we spent part of our honeymoon four years ago and about which I’ve written more than once in this space. Since the point of taking time off is to do nothing, I don’t have any leisurely activities to describe. We slept late, we took a long afternoon drive and looked at the autumn foliage, we sat on the terrace and looked at the Upper Delaware River, we ate a very nice dinner in the quaint little town of Narrowsburg, and we watched a couple of movies.

Oh, yes–I wrote the first draft of a new play. From scratch.

Temporary inactivity, even for so short a span of time, usually recharges my creative batteries, but I wasn’t counting on quite so spectacular a demonstration of its rejuvenating effects. I suppose it would have been better, all things being equal, if I hadn’t written a word at Ecce, but once the coin dropped, I figured I’d better follow it wherever it rolled, and when it kept on rolling, I kept on following. “I guess it’s good that we didn’t have a whole week off,” Mrs. T said with amusement when I announced that the play was finished.

Temporary inactivity, even for so short a span of time, usually recharges my creative batteries, but I wasn’t counting on quite so spectacular a demonstration of its rejuvenating effects. I suppose it would have been better, all things being equal, if I hadn’t written a word at Ecce, but once the coin dropped, I figured I’d better follow it wherever it rolled, and when it kept on rolling, I kept on following. “I guess it’s good that we didn’t have a whole week off,” Mrs. T said with amusement when I announced that the play was finished.

Not really. The truth is that I only managed to skim the cream off the top of my weariness last week. I really do need a week or two off, and I won’t be getting it until January, when we’ll be heading south to Florida for a sun-and-theater “holiday” that will include an uninterrupted span of theoretical inactivity on Sanibel Island, where I wrote three chapters of my Duke Ellington biography this past January.

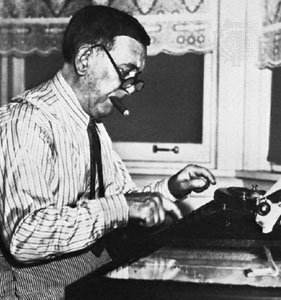

No doubt I’ll get yet another chunk of writing done in Florida. Writing, after all, is what I do, not merely for a living but also for the sheer love of putting words together. I don’t know what I’d do if I couldn’t write. H.L. Mencken, the subject of my first biography, learned the answer to that question when he suffered a stroke in 1948 that deprived him for the last eight years of his life of the power to read and write. It was a hideously ironic fate for a man who had spent the greater part of his waking life pecking away happily at his typewriter, and it chilled me to write about it in The Skeptic.

Yet even Mencken finally managed to come to terms with his fate, as a friend of his later recalled:

Yet even Mencken finally managed to come to terms with his fate, as a friend of his later recalled:

What remained to him of his old joys was music; many mornings he told me how he had listened for a couple of hours the night before and how superb it had been. Yet in truth he had left to him something the average man never acquires–the capacity to enjoy the commonplace activities of life. Though these, of course, could not make up for his inability to work, they helped. One lovely autumn morning, with the sky clear, the breeze cool, and the sun warm, Mr. Mencken sat over in the sun so that it fell on his back. “Well, this is very nice. This is fine. This ought to make us feel good….You know, I always enjoyed life in all its forms. I’ve always taken a great pleasure in getting up in the morning, having breakfast, and settling down to work. I had a good time while it lasted.”

I mean to have an equally good time while it lasts, but should the time ever run out, I hope I can enjoy sitting in the sun as much as Mencken did. That said, I also hope that I never have to relinquish the miraculous, inexplicable joy of settling down to work each day–or the more explicable but no less miraculous joy of taking an occasional day off, a pleasure whose savor is heightened by the preceding day’s work as the flavor of food is heightened by a judicious pinch of salt.

I suppose I’m a workaholic, but it reassures me to know that I can take it or leave it alone. Yesterday I woke up at eight-thirty, looked at the clock, gave brief thought to writing a piece for The Wall Street Journal, then said to myself, The hell with it. Instead I spent the whole day in bed reading Ian Ker’s new biography of G.K. Chesterton, then arose in the evening and went downtown to have dinner with friends and hear Pat Metheny and Larry Grenadier at the Blue Note.

Today belongs to the Journal, but Sunday belonged to me. I had a good time while it lasted, and it lasted all day long.