”Books should be tried by a judge and jury as though they were crimes, and counsel should be heard on both sides.”

Samuel Butler, The Note-Books of Samuel Butler

Archives for September 2011

HOW TWO GREAT CRITICS COMPROMISED THEIR POSTHUMOUS REPUTATIONS

“Clement Greenberg and Virgil Thomson were critics of the first rank. Indeed, Mr. Greenberg was one of the most deservedly influential art critics of the 20th century, while Mr. Thomson is generally regarded as the finest classical-music critic ever to have written for a U.S. newspaper. The world of art would be the poorer had they chosen not to write about it—but for as long as their work is read, some people will wonder whether they could be bought…”

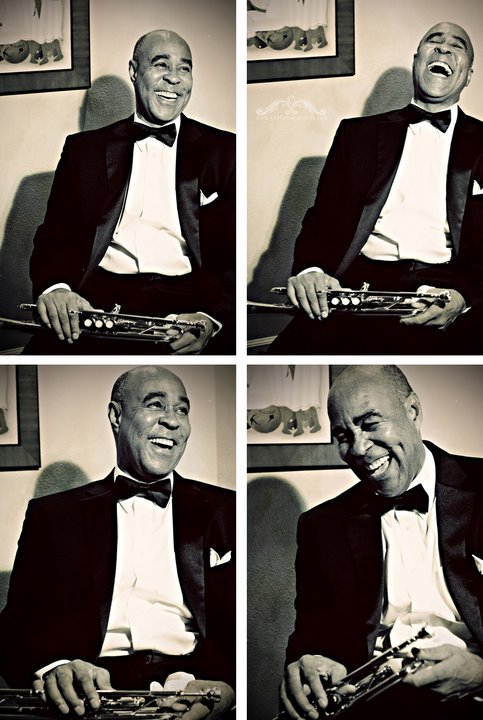

TT: It works

Satchmo at the Waldorf was successful in every way. The house was sold out and the audience gave every indication of loving the show from start to finish. I had no idea that it was so funny. The first act actually played like a comedy. Not so the second half of the second act, which was received in a rapt hush. As for the cheers at the end…well, let’s just call them damned gratifying.

Satchmo at the Waldorf was successful in every way. The house was sold out and the audience gave every indication of loving the show from start to finish. I had no idea that it was so funny. The first act actually played like a comedy. Not so the second half of the second act, which was received in a rapt hush. As for the cheers at the end…well, let’s just call them damned gratifying.

I could spend a lot of time thanking a lot of people, and believe me, I will—but not just yet. I got home a half-hour ago, and I’m so tired I could drop. For now, let me just say that were it not for Hilary Teachout, my beloved Mrs. T, I’d have never worked up the nerve to write my first play, much less to see it through seventeen painstakingly revised drafts and onto the stage of Orlando’s Mandell Theatre. All praise to Dennis Neal, Rus Blackwell, and the rest of my wonderful colleagues, but she comes first.

More anon, but I’ll close with the final speech of the play:

ARMSTRONG (raising his voice) I’m just about done, sugar. (As before) Guess Lucille’s right. Done told my story, said what I gotta say. And now I gotta get to bed, get me some rest like the doc says. Got two shows to play tomorrow, gotta take care of myself. You wanna please the people, get you a good night’s sleep. Playing that pretty music every night take a lot out of an old man.

He puts on his glasses and picks up his trumpet case.

You go that way, I go this way. And we gonna do it all over again tomorrow night. Just like always.

He opens the dressing-room door, switches off the light, and exits, closing the door behind him. Blackout.

See you next week.

UPDATE: To view an album of photos shot at the dress rehearsal of Satchmo at the Waldorf, go here.

TT: “When faith draws blood”

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I write about Hartford Stage’s revival of The Crucible and the Broadway transfer of the Kennedy Center production of Follies. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Time has been unexpectedly kind to “The Crucible.” Arthur Miller’s history play about the Salem witch trials was written at the height of the McCarthy era, and most of the critics who saw it back then found the parallels that Miller drew between Salem in 1693 and Washington, D.C., in 1953 to be grossly heavy-handed. Nor was their displeasure politically motivated. Kenneth Tynan, whose own politics were far to the left of center, wrote that “The Crucible” “has the over-simplifications of poster art.” He was right, too: “The Crucible” is an either/or moral melodrama whose characters are as flat as picket signs. But it is also, like Lillian Hellman’s “The Little Foxes,” a consummately effective piece of theater that carries the emotional charge of a really good B movie. Moreover, the passage of time has made it possible for “The Crucible” to be staged not as a connect-the-dots allegory about McCarthyism but as a cautionary tale of what can happen whenever zealots of any kind—fascists, Communists, religious fanatics, PC enforcers—reach out for the levers of power.

In his riveting Hartford Stage revival of “The Crucible,” Gordon Edelstein has shrewdly cut the play loose from its familiar 17th-century moorings. Ilona Somogyi’s costumes and Eugene Lee’s bare-bones set suggest that the play is taking place early in the 20th century, possibly in the Bible Belt around the time of the Scopes trial. On the other hand, Michael Chybowski has lit the courtroom with fluorescent fixtures that are as modern-looking as a flat-screen TV. The effect is deliberately disorienting, and no sooner is the audience thrown off balance than Mr. Edelstein moves in for the kill. From the slap-in-the-face coup de théâtre that launches the play to the death march that drives it to a thunderous close, this “Crucible” will send your pulse rate shooting through the roof….

In his riveting Hartford Stage revival of “The Crucible,” Gordon Edelstein has shrewdly cut the play loose from its familiar 17th-century moorings. Ilona Somogyi’s costumes and Eugene Lee’s bare-bones set suggest that the play is taking place early in the 20th century, possibly in the Bible Belt around the time of the Scopes trial. On the other hand, Michael Chybowski has lit the courtroom with fluorescent fixtures that are as modern-looking as a flat-screen TV. The effect is deliberately disorienting, and no sooner is the audience thrown off balance than Mr. Edelstein moves in for the kill. From the slap-in-the-face coup de théâtre that launches the play to the death march that drives it to a thunderous close, this “Crucible” will send your pulse rate shooting through the roof….

This is a banner year for “Follies,” the 1971 Stephen Sondheim-James Goldman musical in which the splintered hopes of two middle-aged married couples are flung against the gaudy backdrop of an old-fashioned bring-on-the-girls revue. Not only is Gary Griffin about to stage a major revival of “Follies” for Chicago Shakespeare, but Eric Schaeffer’s superlative Kennedy Center production, which had a deservedly successful run earlier this year in Washington, has just moved to Broadway with its formidable virtues fully intact. Jan Maxwell, Bernadette Peters, Danny Burstein and Ron Raines, the stars of the Kennedy Center cast, are all present and accounted for. Though Ms. Peters is in fragile voice, her acting is touchingly intense, and her colleagues, Mr. Burstein in particular, give powerhouse performances that couldn’t be bettered….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

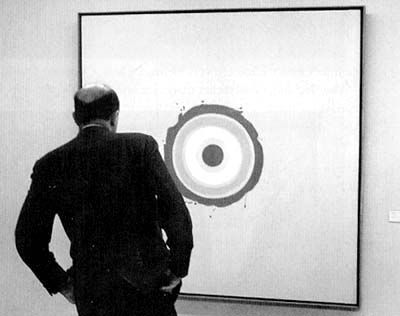

TT: They came bearing gifts

In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal I report on a recent visit to the Portland Art Museum’s Clement Greenberg Collection, and reflect on how Greenberg’s willingness to accept gifts of paintings and sculpture from the artists about whom he wrote has compromised his posthumous reputation. I also have a few sharp words to say about Virgil Thomson, a critic who–unlike Greenberg–really could be bought. Here’s a preview.

* * *

Most critics, like the artists about whom they write, are forgotten soon after they die, if not long before. But Clement Greenberg, whose fervent advocacy put Jackson Pollock on the art-world map, is still well remembered at Oregon’s Portland Art Museum. The Clement Greenberg Collection, on display in Portland since 2001, consists of 155 paintings, sculptures and works on paper by five dozen of the critic’s favorite artists, among them Pollock, Richard Diebenkorn, Helen Frankenthaler, Hans Hofmann, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and David Smith. The installation takes up the better part of a floor, and the best pieces, such as Noland’s “No. One” (1958) and Frankenthaler’s “Spaced Out Orbit” (1973), are spectacular reminders of how Mr. Greenberg, writing in the pages of Partisan Review, The Nation, and other small-press magazines, helped to persuade a generation of Americans that abstract art was the wave of the future.

In his lifetime, Greenberg’s art collection was so admired that Vogue ran a story in 1964 that was illustrated by glossy photographs of his Manhattan apartment, whose walls were covered with paintings. It was quite a sight to see—but it led certain savvy readers to wonder how an art critic, even one as celebrated as Greenberg, had managed to assemble a 155-piece collection of works by some of the most famous American artists of the 20th century. Was he rich? Far from it. The works in his collection were all presented to him as gifts by the grateful artists about whom he wrote. Not only did he accept such gifts, but he sold them whenever he needed money—and after his death in 1994, Greenberg’s widow sold the remaining works in his collection to the Portland Art Museum for two million dollars.

In his lifetime, Greenberg’s art collection was so admired that Vogue ran a story in 1964 that was illustrated by glossy photographs of his Manhattan apartment, whose walls were covered with paintings. It was quite a sight to see—but it led certain savvy readers to wonder how an art critic, even one as celebrated as Greenberg, had managed to assemble a 155-piece collection of works by some of the most famous American artists of the 20th century. Was he rich? Far from it. The works in his collection were all presented to him as gifts by the grateful artists about whom he wrote. Not only did he accept such gifts, but he sold them whenever he needed money—and after his death in 1994, Greenberg’s widow sold the remaining works in his collection to the Portland Art Museum for two million dollars.

Nobody who knew the famously outspoken Greenberg at all well believed that his critical judgment could be swayed by giving him a painting. Moreover, the now-famous artists whom he championed were unknown when he first wrote about them, meaning that their work had little or no monetary value. But in the hard-nosed world of journalism, appearance and reality are inseparably entwined, and today the Greenberg Collection looks less like an eloquent tribute to the sharp eye of a great critic and more like a glaring conflict of interest….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: A week with Satchmo (V)

Louis Armstrong, Velma Middleton, and the All Stars perform “St. Louis Blues”:

TT: Almanac

“Do not be an art critic, but paint, therein lies salvation.”

Paul Cézanne, letter to Emile Bernard, July 25, 1904

TT: More ink

Here’s another excellent preview piece about Satchmo at the Waldorf, this one written by Al Krulick for the Orlando Weekly:

Maybe the moniker “Satchmo” is one you’ve heard. If you’re a fan of the old black-and-white movie musicals, have seen clips from television’s early days or have any interest in jazz or American popular music, you probably know who Louis Armstrong is. You have a mental picture of a broadly smiling, wide-eyed African-American man, stout but debonair, blasting powerful notes on his trumpet, trading quips with Bing Crosby or Ed Sullivan, or perhaps singing “Hello, Dolly” in a voice that sounds like sandpaper rubbing against a human larynx. But if that’s all you know about one of America’s great musical geniuses, you still have much to learn.

Satchmo at the Waldorf, a new play by author and Wall Street Journal theater critic Terry Teachout based on his biography Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, intends to flesh out the details of Armstrong’s long and productive musical life and, according to Teachout, “reveal the man behind the smile.”

The one-man, two-character show will have its world premiere this week at the Orlando Shakespeare Theater. Dennis Neal stars as Louis Armstrong and also as his longtime manager and protector, Joe Glaser, with whom Armstrong had a successful, if fractious, 40-year professional relationship. Well-known Orlando actor and director Rus Blackwell, who has worked with Neal for many years and, with Neal, was one of the founders of the Mad Cow Theatre Company, directs the play.

The coming together of these three talented theater pros was a fortuitous event that Neal opines was destined to occur. According to the highly regarded local performer, “Rus and I had been thinking about doing some sort of one-man show for a long time, but it never came together. When I read Terry’s script, I knew I was born to play this part. I almost felt that it had been written for me.”

Read the whole thing here.