“Nowadays most educated people would just as soon stay home and watch Breaking Bad as shell out a hundred bucks to see a Broadway play–assuming that there are any plays on Broadway worth seeing, which long ago ceased to be a safe bet. So if you can’t make any money writing for the stage, why bother? Putting aside the obvious attraction of being able to make up your own characters, I can think of one excellent reason: You meet the nicest people…”

Archives for September 30, 2011

TT: Home is where the hate is

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review an important off-Broadway revival, Keen Company’s production of Lanford Wilson’s Lemon Sky, and take brief but delighted note of the New Haven transfer of the Irish Rep’s revival of Brian Friel’s Molly Sweeney. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

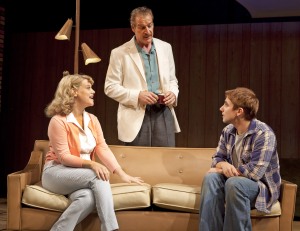

Lanford Wilson was big in the ’70s and ’80s, but the author of “The Hot l Baltimore” and “Talley’s Folly” had largely faded from view by the time of his death in March. It’s been ages since a Wilson play received a high-profile production in New York, and three years since I last reviewed one anywhere in America. For this reason, Keen Company’s Off-Broadway revival of “Lemon Sky” is an occasion of no small consequence, an opportunity to take a second look at a once-admired playwright who has fallen out of fashion–and the news is good. Not only does “Lemon Sky” turn out to be a play of exceptional quality, but Jonathan Silverstein’s production is an extraordinarily strong and finely acted piece of work.

First performed in 1970, revived Off Broadway in 1985 and turned into a TV movie three years after that, “Lemon Sky” is, like so many of Mr. Wilson’s plays, a variation on a theme by Tennessee Williams, a memory play about a sensitive teenage boy (Keith Nobbs) and the boorish father (Kevin Kilner) who doesn’t understand him. The setting is San Diego in the ’50s, that benighted decade of backyard cookouts and wholesome-looking families, and you will not be even slightly surprised to hear that the sensitive teenage boy is gay, while the boorish father turns out to have a few high-voltage kinks of his own. We are, in short, in the land of “The Glass Menagerie,” and no sooner does Alan, Wilson’s fictional stand-in, inform the audience that “I’ve been trying to tell this story, to get it down, for a long time” than you roll your eyes and start thinking about where to have dinner after the show.

First performed in 1970, revived Off Broadway in 1985 and turned into a TV movie three years after that, “Lemon Sky” is, like so many of Mr. Wilson’s plays, a variation on a theme by Tennessee Williams, a memory play about a sensitive teenage boy (Keith Nobbs) and the boorish father (Kevin Kilner) who doesn’t understand him. The setting is San Diego in the ’50s, that benighted decade of backyard cookouts and wholesome-looking families, and you will not be even slightly surprised to hear that the sensitive teenage boy is gay, while the boorish father turns out to have a few high-voltage kinks of his own. We are, in short, in the land of “The Glass Menagerie,” and no sooner does Alan, Wilson’s fictional stand-in, inform the audience that “I’ve been trying to tell this story, to get it down, for a long time” than you roll your eyes and start thinking about where to have dinner after the show.

Well, guess what? You’re in for a surprise–a very big surprise. For even though the plot of “Lemon Sky” is well worn and the premise predictable, Alan tells his tale of woe with a transfiguring intensity far removed from the soft-centered sentimentality of such better-known Wilson plays as “Burn This.” Perhaps because “Lemon Sky” was explicitly autobiographical, Mr. Wilson got the bit between his teeth and ran hard with it, and the result is a play whose angry portrayal of Eisenhower-era family life has the salty sting of remembered truth…

If you missed the Irish Repertory Theatre’s Off-Broadway revival of Brian Friel’s “Molly Sweeney” earlier this year, you can now catch it at Long Wharf Theatre, which is remounting Charlotte Moore’s production on a larger stage. Two of the three original cast members, Jonathan Hogan and Ciarán O’Reilly, are reprising their roles in New Haven, joined by Simone Kirby, who replaced Geraldine Hughes in the title role later in the New York run. Mr. Friel’s masterly play, in which three related monologues are woven around one another like strands of ivy, tells the story of an Irishwoman (Ms. Kirby) who has been blind since childhood and whose sight is miraculously restored by surgery in middle age. What follows is a parable of false hope and devastating disappointment, staged by Ms. Moore with gentle grace, performed to perfection by her cast and lit with special delicacy by Michael Gottlieb and Richard Pilbrow….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Why would anybody write a play?

Satchmo at the Waldorf closes in Orlando on Sunday afternoon. Would that I were there! Not surprisingly, the experience of writing my first play and seeing it onto the stage has inspired me to write a “Sightings” column in which I talk about some of the things I learned along the way. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Tony Kushner can’t make a living writing for the stage. America’s most prominent playwright confessed in an interview published in Time Out New York earlier this year that “Angels in America” doesn’t pay the rent: “I make my living now as a screenwriter! Which I’m surprised and horrified to find myself saying, but I don’t think I can support myself as a playwright at this point. I don’t think anybody does.” So far as I know, Mr. Kushner is right. I don’t know of any American playwrights who earn the bulk of their living writing plays. Many of the older ones teach, while a growing number of younger ones write for series TV. Itamar Moses, for instance, has written for “Boardwalk Empire” and “Men of a Certain Age,” which isn’t stopping him from turning out stage plays (his latest effort, “Completeness,” just closed Off Broadway).

The question all but asks itself: Why is anybody still writing plays? Theater, after all, is no longer a central part of the American cultural conversation, the way it was when Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams walked the earth. Nowadays most educated people would just as soon stay home and watch “Breaking Bad” as shell out a hundred bucks to see a Broadway play–assuming that there are any plays on Broadway worth seeing, which long ago ceased to be a safe bet.

So if you can’t make any money writing for the stage, why bother? Putting aside the obvious attraction of being able to make up your own characters, I can think of one excellent reason: You meet the nicest people.

You’ve probably never thought about it before unless you happen to write for a living, but professional writers are doomed to spend most of their waking hours sitting by themselves at a desk, staring at a blank computer screen and waiting for lightning to strike. It’s a lonely business, which explains why a few authors choose to collaborate instead of flying solo. Moss Hart, who wrote his best plays in partnership with George S. Kaufman, explained his decision to write with a partner in “Act One,” his 1959 autobiography: “The hardest part of writing by far is the seeming exclusion from all humankind while work is under way, for the writer at work cannot be gregarious….Collaboration cuts this loneliness in half. When one is at a low point of discouragement, the very presence in the room of another human being, even though he too may be sunk in the same state of gloom, very often gives that dash of valor to the spirit that allows confidence to return and work to resume.”

You’ve probably never thought about it before unless you happen to write for a living, but professional writers are doomed to spend most of their waking hours sitting by themselves at a desk, staring at a blank computer screen and waiting for lightning to strike. It’s a lonely business, which explains why a few authors choose to collaborate instead of flying solo. Moss Hart, who wrote his best plays in partnership with George S. Kaufman, explained his decision to write with a partner in “Act One,” his 1959 autobiography: “The hardest part of writing by far is the seeming exclusion from all humankind while work is under way, for the writer at work cannot be gregarious….Collaboration cuts this loneliness in half. When one is at a low point of discouragement, the very presence in the room of another human being, even though he too may be sunk in the same state of gloom, very often gives that dash of valor to the spirit that allows confidence to return and work to resume.”

To be sure, most playwrights, unlike Hart, write by themselves. Once a script is finished, though, they immediately plunge themselves into the endlessly pleasurable frenzy of a collaborative enterprise….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“I have never understood this liking for war. It panders to instincts already catered for within the scope of any respectable domestic establishment.”

Alan Bennett, Forty Years On