Mrs. T and I spent most of last week seeing four plays at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Today we drive back to Portland, then fly from there to Chicago. We were supposed to spend the night at an airport hotel, then drive up to Spring Green, Wisconsin, home of American Players Theatre and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, there to spend another week seeing another four plays.

Mrs. T and I spent most of last week seeing four plays at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Today we drive back to Portland, then fly from there to Chicago. We were supposed to spend the night at an airport hotel, then drive up to Spring Green, Wisconsin, home of American Players Theatre and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, there to spend another week seeing another four plays.

Life, however, dealt us a fresh hand: my mother had emergency surgery in Missouri on Sunday afternoon and will likely have a second operation on Tuesday. It isn’t easy to get from southern Oregon to southeast Missouri, so we won’t be arriving in Smalltown, U.S.A. until well after midnight.

Needless to say, that’s a whole lot of travel, and we expect to be completely worn out by the time we finally get where we’re going, so don’t expect anything more than brief updates for the rest of the week.

For now, I’ll pass on a posting by Levi Stahl, who’s gotten hold of the new University of Chicago Press paperback editions of Richard Stark’s Flashfire and Firebreak and likes my introductions. He’s ahead of me: I’ve been on the road for the past couple of weeks and have yet to see finished copies of either book.

As for the week just past, suffice it to say that I’m exceedingly partial to Ashland, home of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The only reason why I’m not sorry to say goodbye is that I like Spring Green just as much, and with a little bit of luck–well, maybe a whole lot of luck–we’ll be there by Friday night.

More anon.

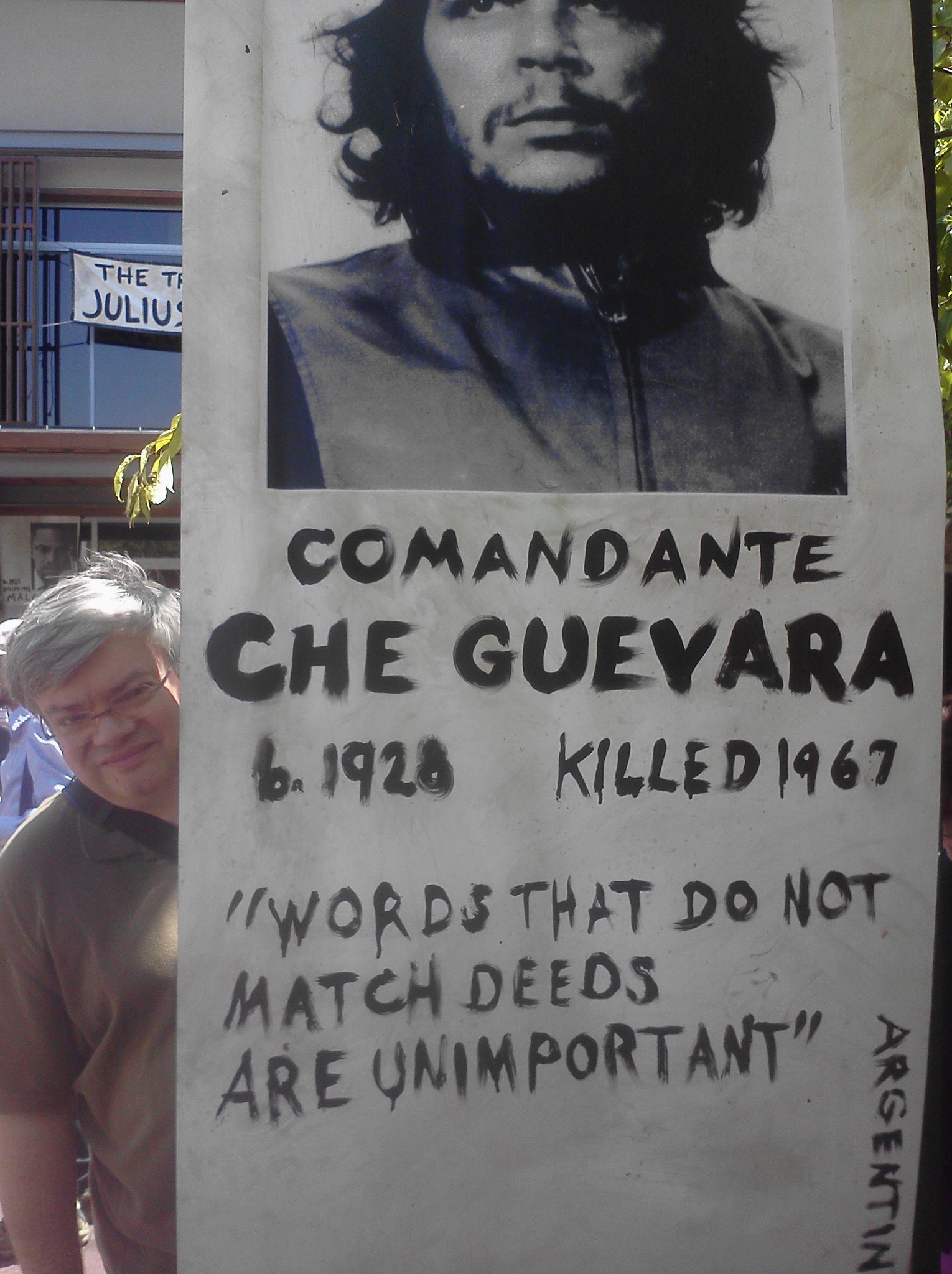

P.S. Mrs. T took this photo outside the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s New Theatre, where we saw Amanda Dehnert’s production of Julius Caesar on Friday. The courtyard and lobby are decorated with similar posters of various politicians who have been assassinated. It amused Mrs. T to see me standing next to Che Guevara, especially in light of the fact that the city where we saw the play in question is popularly known among its own residents as “The People’s Republic of Ashland.” (Earlier that day I’d seen a teenage boy wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with that very nickname.)

P.S. Mrs. T took this photo outside the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s New Theatre, where we saw Amanda Dehnert’s production of Julius Caesar on Friday. The courtyard and lobby are decorated with similar posters of various politicians who have been assassinated. It amused Mrs. T to see me standing next to Che Guevara, especially in light of the fact that the city where we saw the play in question is popularly known among its own residents as “The People’s Republic of Ashland.” (Earlier that day I’d seen a teenage boy wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with that very nickname.)

I really do love Ashland. Mostly. Usually. Frequently.

Archives for August 2011

TT: Just because

Carmen McRae sings Alec Wilder’s “Trouble Is a Man” on Jazz Casual, originally telecast in 1962:

TT: Almanac

“As much as gastronomy applauds novelty, it is based in equal part on nostalgia. In the mind, food, being an ephemeral creation prepared from ephemeral materials, is necessarily located in the past, and there is a tendency to believe that the best must behind us; that, in a sort of theory of epicurean entrophy, flavor and goodness are ebbing as time moves forward.”

Robert Clark, James Beard: A Biography

MAKING SHAKESPEARE SING: A MODEST PROPOSAL FOR A COSTLY FESTIVAL

“Sure, it’s interesting to read about how Verdi and Britten turned three of Shakespeare’s greatest plays into equally great operas, but wouldn’t it be even more interesting to see the plays and operas side by side? Needless to say, such an undertaking would be both cruelly expensive and logistically nightmarish, but it could be done in a festival setting—and New York’s Lincoln Center Festival and Washington’s Kennedy Center are both capable of making it happen…”

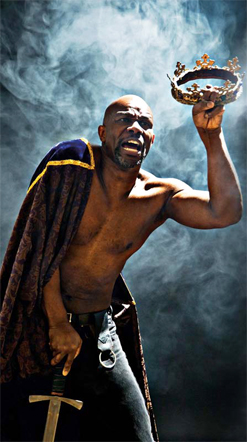

TT: Young prince in a jam

In today’s Wall Street Journal I report on two of this summer’s Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival productions, Hamlet and The Comedy of Errors. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

How old is Hamlet? That’s neither a joke nor a riddle, but a question that anyone who stages the most celebrated of Shakespeare’s tragedies must start by answering. We know that Hamlet is a prince, which presumably (though not necessarily) means that he’s a young man. We also know that he’s in love with Ophelia, who is clearly a girl on the brink of womanhood. But “Hamlet” poses formidable challenges for the actor who plays the title role, and the play’s extreme familiarity makes them all the more daunting. If you cast an experienced performer as Hamlet, you run the risk of lessening the verisimilitude of the production–but no unseasoned actor, however promising, can do much more than sketch the outlines of so complex a part.

So what to do? Terrence O’Brien, the artistic director of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, chose not to split the difference when casting the 25-year-old company’s first “Hamlet.” Not only is Matthew Amendt very young–this is his second season with the festival–but most of the other parts are played by similarly fresh-looking faces, and Mr. O’Brien underlines their youth by accompanying the show with thunderous heavy-metal rock (plus a regal-sounding fanfare borrowed from William Schuman’s “George Washington Bridge”). Yet this is by no means a trendy “Hamlet,” for Mr. O’Brien, as is his wont, has steered clear of the conceptual approach beloved of today’s Shakespeare directors. His staging is unapologetically, even aggressively plain, and every detail of the play has been rethought from scratch, with ever-surprising results. Even the modern-dress costumes of Charlotte Palmer-Lane have an unexpected touch of dandyishness. The results are a bit raw but altogether involving. I’ve never seen a more attentive “Hamlet” audience–or heard a quieter one.

So what to do? Terrence O’Brien, the artistic director of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, chose not to split the difference when casting the 25-year-old company’s first “Hamlet.” Not only is Matthew Amendt very young–this is his second season with the festival–but most of the other parts are played by similarly fresh-looking faces, and Mr. O’Brien underlines their youth by accompanying the show with thunderous heavy-metal rock (plus a regal-sounding fanfare borrowed from William Schuman’s “George Washington Bridge”). Yet this is by no means a trendy “Hamlet,” for Mr. O’Brien, as is his wont, has steered clear of the conceptual approach beloved of today’s Shakespeare directors. His staging is unapologetically, even aggressively plain, and every detail of the play has been rethought from scratch, with ever-surprising results. Even the modern-dress costumes of Charlotte Palmer-Lane have an unexpected touch of dandyishness. The results are a bit raw but altogether involving. I’ve never seen a more attentive “Hamlet” audience–or heard a quieter one.

Mr. Amendt is already more than good enough to make you wonder what he’ll be doing, and where he’ll be doing it, five years down the road. He looks more than a bit like Matt Dillon, and he brings to the part a bitingly sarcastic tone that is as contemporary as his physical appearance….

Hudson Valley’s institutional knack for zaniness, of which occasional flashes can be seen in “Hamlet,” is given free rein in Kurt Rhoads’ circus-themed production of “The Comedy of Errors,” in which we meet such cartoonish characters as a magenta-bearded lady (Katie Hartke), an eye-shadowed mermaid in a wheelchair (Valeri Mudek) and a three-breasted courtesan (Maura Clement). Looniest of all are the two Dromios, Nance Williamson and Gabra Zackman, whom Mr. Rhoads and Amy Clark, the costume designer, have made over in the surreal image of Pat, the androgyne played by Julia Sweeney on “Saturday Night Live.”

All this trickery goes well with the broad-brush slapstick of Shakespeare’s most concise comedy…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Making Shakespeare sing

While we’re on the subject of the immortal bard, my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal consists of a modest Shakespeare-related proposal for Lincoln Center and Kennedy Center. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

How do you write a successful opera? Most well-known operas, like most well-known musicals, are adapted from equally well-known plays or novels. And who is the most famous writer of all time? William Shakespeare! So all you have to do is take a Shakespeare play and turn it into an opera…and what could be easier? Just add great music and you’ve got a hit. Right?

How do you write a successful opera? Most well-known operas, like most well-known musicals, are adapted from equally well-known plays or novels. And who is the most famous writer of all time? William Shakespeare! So all you have to do is take a Shakespeare play and turn it into an opera…and what could be easier? Just add great music and you’ve got a hit. Right?

Er, no. Not even close.

Consider the odds. To date, some 200 operas have been based on Shakespeare’s plays. Only two of them, Giuseppe Verdi’s “Otello” (1887) and “Falstaff” (1893, based on “The Merry Wives of Windsor”), are solidly entrenched in the international opera-house repertoire. A handful of others, the best of which are Verdi’s “Macbeth” (1847) and Benjamin Britten’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1960), are revived with fair frequency. The rest are forgotten. Clearly, anybody who thinks that setting Shakespeare is a sure-fire recipe for success needs to think again—and again and again.

As for the second part of the “recipe,” you have to do more to a Shakespeare play than add music—even great music—to turn it into a opera that works in the theater….

As for the second part of the “recipe,” you have to do more to a Shakespeare play than add music—even great music—to turn it into a opera that works in the theater….

Writing an opera based on a familiar literary source, be it by Shakespeare or Maugham or Lillian Hellman, demands a far-reaching imaginative transformation of the original text, one that goes beyond the mere setting of old words to new music. In writing the libretti for “Falstaff” and “Otello,” for instance, Arrigo Boito freely translated Shakespeare’s English words into Italian, adding ideas of his own that were inspired by Shakespeare. Sacrilege? Not at all. That very freedom made it possible for Boito to steer clear of a literal approach to “The Merry Wives of Windsor” and “Othello” and write the beautifully crafted libretti that inspired Verdi to compose his two greatest operas….

Are you thinking what I’m thinking? Sure, it’s interesting to read about how Verdi and Britten turned three of Shakespeare’s greatest plays into equally great operas, but wouldn’t it be even more interesting to see the plays and operas side by side? Needless to say, such an undertaking would be both cruelly expensive and logistically nightmarish, but it could be done in a festival setting—and New York’s Lincoln Center Festival and Washington’s Kennedy Center are both capable of making it happen….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“We only do well the things we like doing.”

Colette, Prisons and Paradise

TT: Two little tastes

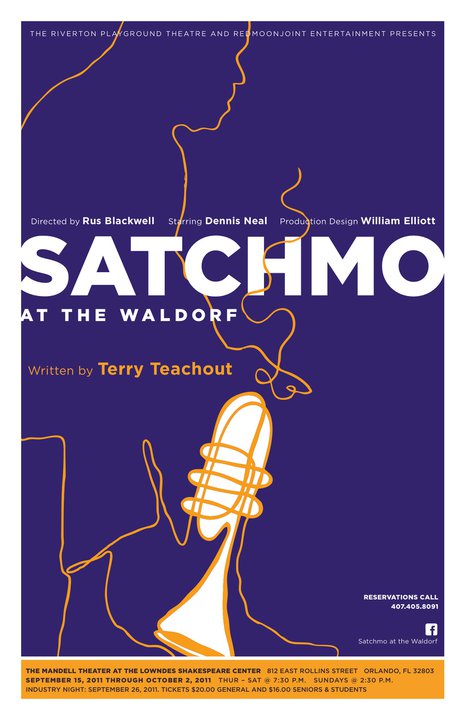

As the September 15 premiere of Satchmo at the Waldorf draws nearer in Orlando, Florida, Dennis Neal, the star, has e-mailed me a copy of the poster that will be used for the show. I know appearances aren’t everything, but I can’t see how anyone wouldn’t want to buy a ticket after seeing this gorgeous piece of work.

As the September 15 premiere of Satchmo at the Waldorf draws nearer in Orlando, Florida, Dennis Neal, the star, has e-mailed me a copy of the poster that will be used for the show. I know appearances aren’t everything, but I can’t see how anyone wouldn’t want to buy a ticket after seeing this gorgeous piece of work.

I’ve been meaning to post an excerpt from the script, but Satchmo at the Waldorf is not suitable for families–unless, of course, you’re the sort of parent who wouldn’t think twice about taking the kids to see American Buffalo–and this blog has long had a policy of not printing certain high-voltage words. Fortunately, though, there are a couple of speeches that are reasonably clean, so I thought I’d share one of them with you. It comes from the second act, in which Louis Armstrong is looking back on his childhood from the vantage point of old age. (The play is set in a dressing room at the Waldorf-Astoria, where Armstrong played in public for the last time four months before his death in 1971.)

Here it is:

Fragments of Armstrong’s music play softly in the background, as if they were being heard from far off.

ARMSTRONG (over the music) The block in New Orleans where I was born was so tough, they done called it “The Battleground.” One-room shack, outhouse in back, wash in a laundry tub. My sister and me, we use to go through the garbage cans out back of all them fine restaurants, pick through ’em for the taters and onions wasn’t too spoiled, bring ’em home to Mayann. But we didn’t eat ’em. Oh, no—we dressed ’em. Cut off all the spoiled parts, then I go out and sell ’em to them other restaurants, the ones ain’t so fine, bring back a little extra change to go with the coal money.

Sometimes I go to sleep at night and dream about going through them garbage cans, hope to find a couple taters ain’t too rotten to take home. ’Bout riding the junk wagon and driving my mule. Sometimes I dream about the music I heard in the street when I was a kid. Or I dream I’m lying in bed at the Waif’s Home, smelling the magnolias and the honeysuckle through the window after they put the lights out. I can smell ’em now, just like I’m there. Smell ’em in the middle of the night and I say to myself, what’m I doing sleeping in a suite in the Waldorf? How’d I get so lucky?

Luck’s a funny thing. Poor old Joe Oliver, he done run shit outta luck. Teeth went bad on him, couldn’t play his horn no more. Went back down south, busted flat. I was touring with the band in Savannah, walking down the street, see this sad old cat pushing a vegetable cart, and it’s Papa Joe. Like to broke my heart. I gave him all the money I had in my pocket. Boys in the band all did the same. That night he come to this colored dance we playing and he was dressed up fine, looking sharp, holding his head up high.

That was the last time I saw Papa Joe. He died pretty soon after that. Didn’t have no luck. I had all the luck….

If you like how that sounds, come on down to Orlando and see the show!

UPDATE: For those who asked about the poster, the creative director is Bryan Kriekard and the designer is Blake Everingham. Thanks, guys!

* * *

Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington perform Ellington’s “Azalea” in 1962. The lyrics, also by Ellington, were inspired by Armstrong’s memories of the flowers that bloomed in the New Orleans of his youth: