“Sure, it’s interesting to read about how Verdi and Britten turned three of Shakespeare’s greatest plays into equally great operas, but wouldn’t it be even more interesting to see the plays and operas side by side? Needless to say, such an undertaking would be both cruelly expensive and logistically nightmarish, but it could be done in a festival setting—and New York’s Lincoln Center Festival and Washington’s Kennedy Center are both capable of making it happen…”

Archives for August 19, 2011

TT: Young prince in a jam

In today’s Wall Street Journal I report on two of this summer’s Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival productions, Hamlet and The Comedy of Errors. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

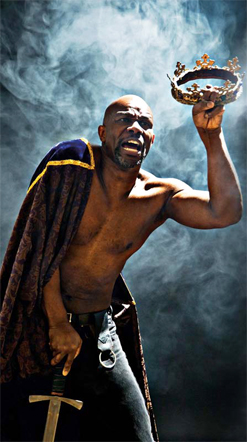

How old is Hamlet? That’s neither a joke nor a riddle, but a question that anyone who stages the most celebrated of Shakespeare’s tragedies must start by answering. We know that Hamlet is a prince, which presumably (though not necessarily) means that he’s a young man. We also know that he’s in love with Ophelia, who is clearly a girl on the brink of womanhood. But “Hamlet” poses formidable challenges for the actor who plays the title role, and the play’s extreme familiarity makes them all the more daunting. If you cast an experienced performer as Hamlet, you run the risk of lessening the verisimilitude of the production–but no unseasoned actor, however promising, can do much more than sketch the outlines of so complex a part.

So what to do? Terrence O’Brien, the artistic director of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, chose not to split the difference when casting the 25-year-old company’s first “Hamlet.” Not only is Matthew Amendt very young–this is his second season with the festival–but most of the other parts are played by similarly fresh-looking faces, and Mr. O’Brien underlines their youth by accompanying the show with thunderous heavy-metal rock (plus a regal-sounding fanfare borrowed from William Schuman’s “George Washington Bridge”). Yet this is by no means a trendy “Hamlet,” for Mr. O’Brien, as is his wont, has steered clear of the conceptual approach beloved of today’s Shakespeare directors. His staging is unapologetically, even aggressively plain, and every detail of the play has been rethought from scratch, with ever-surprising results. Even the modern-dress costumes of Charlotte Palmer-Lane have an unexpected touch of dandyishness. The results are a bit raw but altogether involving. I’ve never seen a more attentive “Hamlet” audience–or heard a quieter one.

So what to do? Terrence O’Brien, the artistic director of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, chose not to split the difference when casting the 25-year-old company’s first “Hamlet.” Not only is Matthew Amendt very young–this is his second season with the festival–but most of the other parts are played by similarly fresh-looking faces, and Mr. O’Brien underlines their youth by accompanying the show with thunderous heavy-metal rock (plus a regal-sounding fanfare borrowed from William Schuman’s “George Washington Bridge”). Yet this is by no means a trendy “Hamlet,” for Mr. O’Brien, as is his wont, has steered clear of the conceptual approach beloved of today’s Shakespeare directors. His staging is unapologetically, even aggressively plain, and every detail of the play has been rethought from scratch, with ever-surprising results. Even the modern-dress costumes of Charlotte Palmer-Lane have an unexpected touch of dandyishness. The results are a bit raw but altogether involving. I’ve never seen a more attentive “Hamlet” audience–or heard a quieter one.

Mr. Amendt is already more than good enough to make you wonder what he’ll be doing, and where he’ll be doing it, five years down the road. He looks more than a bit like Matt Dillon, and he brings to the part a bitingly sarcastic tone that is as contemporary as his physical appearance….

Hudson Valley’s institutional knack for zaniness, of which occasional flashes can be seen in “Hamlet,” is given free rein in Kurt Rhoads’ circus-themed production of “The Comedy of Errors,” in which we meet such cartoonish characters as a magenta-bearded lady (Katie Hartke), an eye-shadowed mermaid in a wheelchair (Valeri Mudek) and a three-breasted courtesan (Maura Clement). Looniest of all are the two Dromios, Nance Williamson and Gabra Zackman, whom Mr. Rhoads and Amy Clark, the costume designer, have made over in the surreal image of Pat, the androgyne played by Julia Sweeney on “Saturday Night Live.”

All this trickery goes well with the broad-brush slapstick of Shakespeare’s most concise comedy…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Making Shakespeare sing

While we’re on the subject of the immortal bard, my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal consists of a modest Shakespeare-related proposal for Lincoln Center and Kennedy Center. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

How do you write a successful opera? Most well-known operas, like most well-known musicals, are adapted from equally well-known plays or novels. And who is the most famous writer of all time? William Shakespeare! So all you have to do is take a Shakespeare play and turn it into an opera…and what could be easier? Just add great music and you’ve got a hit. Right?

How do you write a successful opera? Most well-known operas, like most well-known musicals, are adapted from equally well-known plays or novels. And who is the most famous writer of all time? William Shakespeare! So all you have to do is take a Shakespeare play and turn it into an opera…and what could be easier? Just add great music and you’ve got a hit. Right?

Er, no. Not even close.

Consider the odds. To date, some 200 operas have been based on Shakespeare’s plays. Only two of them, Giuseppe Verdi’s “Otello” (1887) and “Falstaff” (1893, based on “The Merry Wives of Windsor”), are solidly entrenched in the international opera-house repertoire. A handful of others, the best of which are Verdi’s “Macbeth” (1847) and Benjamin Britten’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1960), are revived with fair frequency. The rest are forgotten. Clearly, anybody who thinks that setting Shakespeare is a sure-fire recipe for success needs to think again—and again and again.

As for the second part of the “recipe,” you have to do more to a Shakespeare play than add music—even great music—to turn it into a opera that works in the theater….

As for the second part of the “recipe,” you have to do more to a Shakespeare play than add music—even great music—to turn it into a opera that works in the theater….

Writing an opera based on a familiar literary source, be it by Shakespeare or Maugham or Lillian Hellman, demands a far-reaching imaginative transformation of the original text, one that goes beyond the mere setting of old words to new music. In writing the libretti for “Falstaff” and “Otello,” for instance, Arrigo Boito freely translated Shakespeare’s English words into Italian, adding ideas of his own that were inspired by Shakespeare. Sacrilege? Not at all. That very freedom made it possible for Boito to steer clear of a literal approach to “The Merry Wives of Windsor” and “Othello” and write the beautifully crafted libretti that inspired Verdi to compose his two greatest operas….

Are you thinking what I’m thinking? Sure, it’s interesting to read about how Verdi and Britten turned three of Shakespeare’s greatest plays into equally great operas, but wouldn’t it be even more interesting to see the plays and operas side by side? Needless to say, such an undertaking would be both cruelly expensive and logistically nightmarish, but it could be done in a festival setting—and New York’s Lincoln Center Festival and Washington’s Kennedy Center are both capable of making it happen….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“We only do well the things we like doing.”

Colette, Prisons and Paradise