In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal I pay tribute to Terence Rattigan, a major twentieth-century playwright whose work is now virtually unknown in the United States. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Tennessee Williams was born a hundred years ago last week, and if there haven’t been many celebrations, it’s because they aren’t necessary. His best plays are performed regularly throughout America, and he is universally regarded as one of our greatest writers. But 2011 is also the centenary of Terence Rattigan’s birth, yet you’d be hard pressed to find anyone on this side of the Atlantic who is aware of the fact. Indeed, few American theatergoers are likely even to recognize Rattigan’s name, much less to know that the author of “Separate Tables” and “The Winslow Boy” was one of the 20th century’s most popular and successful playwrights. I’ve written scarcely a word about him in this paper’s drama column. Why? Because none of his two dozen plays, so far as I know, has received a major professional production in the U.S. since I became the Journal’s theater critic in 2003….

Why did Rattigan drop off the scope? Because he specialized in stylish, “well-made” plays about the English middle class and its deceptively genteel discontents. “I believe that the best plays are about people and not about things.” Rattigan wrote in 1950, and back then most people agreed with him. Starting in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a new generation of politically conscious playwrights like John Osborne and Shelagh Delaney started writing harsh portrayals of life on the wrong side of the tracks, and within a matter of years the determinedly apolitical Rattigan had become a period piece. But now that the “swinging ’60s” have themselves passed into history, it’s possible once again for English playgoers to unapologetically savor his sharp wit and elegant craftsmanship.

Why did Rattigan drop off the scope? Because he specialized in stylish, “well-made” plays about the English middle class and its deceptively genteel discontents. “I believe that the best plays are about people and not about things.” Rattigan wrote in 1950, and back then most people agreed with him. Starting in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a new generation of politically conscious playwrights like John Osborne and Shelagh Delaney started writing harsh portrayals of life on the wrong side of the tracks, and within a matter of years the determinedly apolitical Rattigan had become a period piece. But now that the “swinging ’60s” have themselves passed into history, it’s possible once again for English playgoers to unapologetically savor his sharp wit and elegant craftsmanship.

What is harder to say is whether Rattigan’s plays have any chance of finding an audience in the U.S. The problem is that virtually all of his best work is permeated with two quintessentially English themes that are unusually difficult for American actors and directors to understand: class differences and emotional inhibition. In a Rattigan play, you never have to ask where a character went to school or what he does for a living. You can tell by his accent–or his tie….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

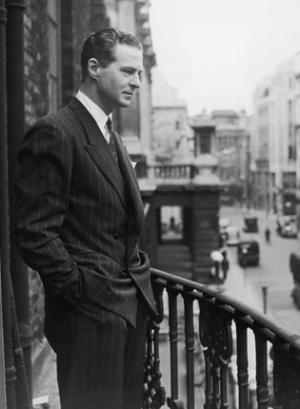

A scene from the 1951 film version of Rattigan’s The Browning Version, starring Michael Redgrave:

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog