“Accepting life whole and keeping one’s love of art from idolatry means remembering that nonliving things must be loved soberly. The living have first claim, and fellow feeling for them should stir not only at the sight of sorrow and pain, but at the call of the imagination.”

Jacques Barzun, “Towards a Fateful Serenity” (courtesy of Anecdotal Evidence)

Archives for April 2011

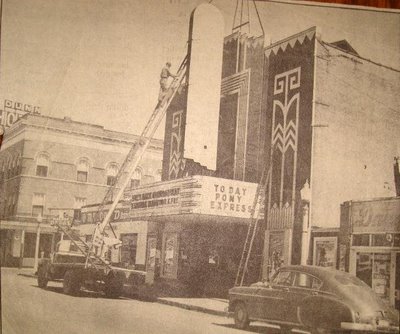

TT: The first picture show

I first saw a movie in a theater in 1961. It was Dondi, a now-forgotten screen version of a now-forgotten comic strip about an adorable little war orphan who makes his circuitous way from Italy to the United States, there to have all manner of adventures and live happily ever after.

I first saw a movie in a theater in 1961. It was Dondi, a now-forgotten screen version of a now-forgotten comic strip about an adorable little war orphan who makes his circuitous way from Italy to the United States, there to have all manner of adventures and live happily ever after.

The film, which starred David Janssen, Arnold Stang, Patti Page, and Walter Winchell, appears to have sunk without trace. So did the strip, which ran from 1955 to 1986, at which time it was carried by a mere thirty-five newspapers. The only reason why I remember either one is because according to family legend, I was asked to leave the theater midway through the show. It seems that I was so excited by Dondi that I insisted on running up and down the aisle, which in 1961 was universally regarded as conduct unbecoming a filmgoer, even one who was, like me, just five years old.

Most films, however musty, surface on Turner Classic Movies sooner or later. When Dondi popped up there the other day, I made a point of recording it for future viewing, and last night I took an amused peek at my very first movie. Somewhat surprisingly, the first reel, in which poor little Dondi finds refuge from a snowstorm in a shabby-looking Army barracks, had a vaguely familiar look to me. Was it possible that the first few minutes of Dondi had impressed themselves on my memory? Surely not–and yet it’s true that I’ve retained a handful of other visual fragments of my pre-school days. Among other things, I clearly remember seeing Edward R. Murrow on Person to Person, a show that Murrow stopped hosting in 1959. If I can remember that, it’s well within the realm of possibility that I can also recall a snippet or two of Dondi, at least up to the point when Hodge Decker, the dapper manager of the Malone Theater, gave me the boot.

The Malone, the movie house in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I saw Dondi, no longer exists. It was closed and torn down in 1985, a year before the comic strip bit the dust and eleven years after I moved away from the Missouri town where I grew up. I must have attended a fair number of Saturday matinees there, but the names of the other films that I saw have all faded from my memory. Nor do I have any sexy memories to share with you, for I was a pitifully slow learner when it came to women, and I don’t think I worked up the nerve to fondle anyone at the Malone other than tentatively.

The Malone, the movie house in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I saw Dondi, no longer exists. It was closed and torn down in 1985, a year before the comic strip bit the dust and eleven years after I moved away from the Missouri town where I grew up. I must have attended a fair number of Saturday matinees there, but the names of the other films that I saw have all faded from my memory. Nor do I have any sexy memories to share with you, for I was a pitifully slow learner when it came to women, and I don’t think I worked up the nerve to fondle anyone at the Malone other than tentatively.

As for Dondi, it’s not the worst picture I’ve ever seen, though only sentiment can explain why I watched the whole thing last night. As longtime readers of this blog know, I am one of those blessed creatures who had a largely happy childhood and who moved away from home not out of discontent but to seek out opportunities that were unavailable in a small Midwestern town. Had I taken my father’s advice and become a lawyer, I probably would have come back to Smalltown, settled down, made something of myself, and–like little Dondi–lived happily ever after.

Or not: the small towns of America, it’s said, used to be full of unhappy misfits who frittered away their lives longing for that which they could never hope to have. This may well be true, but most everybody who lived in Smalltown when I was a boy seems to have managed to do so with a minimum of fuss, and those who couldn’t usually packed up and left. Nowadays, of course, the word “provincial” has lost most of its meaning and much of its sting, since we all live in the same electronic echo chamber. It’s as easy to watch Treme or download “Born This Way” in Smalltown as it is in Manhattan. But I can remember when it took at least a month for the movies I read about in Time to get to the Malone, and many of the ones that sounded most interesting never got there at all. Though network television had started to shrink the world in 1961, its effects were gradual and fitful. In those days placing a long-distance telephone call was still a big deal, and the only person in America who carried his own phone around with him was Dick Tracy.

Or not: the small towns of America, it’s said, used to be full of unhappy misfits who frittered away their lives longing for that which they could never hope to have. This may well be true, but most everybody who lived in Smalltown when I was a boy seems to have managed to do so with a minimum of fuss, and those who couldn’t usually packed up and left. Nowadays, of course, the word “provincial” has lost most of its meaning and much of its sting, since we all live in the same electronic echo chamber. It’s as easy to watch Treme or download “Born This Way” in Smalltown as it is in Manhattan. But I can remember when it took at least a month for the movies I read about in Time to get to the Malone, and many of the ones that sounded most interesting never got there at all. Though network television had started to shrink the world in 1961, its effects were gradual and fitful. In those days placing a long-distance telephone call was still a big deal, and the only person in America who carried his own phone around with him was Dick Tracy.

Was the world of my childhood better, worse, or just different? All of the above, I should think. Sometimes I wish I still lived there, but it goes without saying that I would have had to live in a place not unlike New York in order to do the things that I’d want to be doing now. I was, however, content to live in Smalltown in 1961, and almost as content in 1971. My mother and brother still live there, and I’ve yet to hear either one of them complain about it.

All in all, I think I was lucky to live there when I did, just as I was lucky to move to New York when I did. In fact, I think I’m a pretty lucky guy all around–even if I did get thrown out of the Malone Theater fifty years ago for running up and down the aisle.

TT: See me, hear me

From time to time I get spotted in public, occasionally with unpredictable results. I’ve relieved to say that I’ve never gotten a right to the jaw or a pie in the face, but last Friday I was standing in front of the Stephen Sondheim Theatre, waiting to see Anything Goes, when an older fellow with a perfect Mittel-European accent walked right up to me, peered in my face, and said, “You’re the guy who wrote the book about Louis Armstrong? I read it. I recognized your face! Nice to see you!” He then vanished into the crowd, leaving me…well, bemused, I guess. I hope he liked it.

From time to time I get spotted in public, occasionally with unpredictable results. I’ve relieved to say that I’ve never gotten a right to the jaw or a pie in the face, but last Friday I was standing in front of the Stephen Sondheim Theatre, waiting to see Anything Goes, when an older fellow with a perfect Mittel-European accent walked right up to me, peered in my face, and said, “You’re the guy who wrote the book about Louis Armstrong? I read it. I recognized your face! Nice to see you!” He then vanished into the crowd, leaving me…well, bemused, I guess. I hope he liked it.

I’m always happy to accept compliments (if that’s what this was) from strangers on the sidewalk, but if you’d like to have a more extended face-to-face encounter with me this week, here are two opportunities:

• On Tuesday in Manhattan I’ll be presenting excerpts from Danse Russe, my new operatic collaboration with Paul Moravec, as part of a midday program at the Jewish Community Center, which is located at 334 Amsterdam. The show starts at 12:30 p.m.

For more information, go here.

To read more about the arts festival of which Danse Russe (which opens in Philadelphia on April 28) is a part, go here.

• On Sunday I’ll be in Malvern, Pennsylvania, taking part in a public conversation with Abigail Adams, the artistic director of People’s Light & Theatre, one of my favorite regional theater companies. Our subject is Horton Foote, whose Dividing the Estate is about to be staged by PL&T (the production opens on May 11). The event starts at six o’clock.

For more information, go here.

TT: Almanac

“There could be no honor in a sure success, but much might be wrested from a sure defeat.”

T.E. Lawrence, Revolt in the Desert

TT: Toothless Tiger

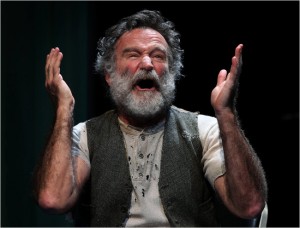

It’s back to business as usual on Broadway: I do the job on Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo in today’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

If you’re a movie star, you can do pretty much anything you want on Broadway. You can make your stage debut there, regardless of whether you’ve ever performed in front of an audience. You can be the leading man in a musical, despite the pesky fact that you’ve never sung anywhere but in your shower. You can even finagle a bunch of producers into putting up the cash to mount an ostensibly serious new play, the kind that normally wouldn’t have a chance of opening anywhere near Times Square. Which explains the unlikely presence on Broadway of Rajiv Joseph’s “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo,” a symbolic drama about the horrors of the war in Iraq that has just transferred to New York from the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Los Angeles with a single cast change: Robin Williams is making his Broadway debut in the title role….

Mr. Williams’ tiger is a foul-mouthed comedian-predator who is shot to death by Kev (Brad Fleischer), a loutishly stupid American soldier, when he bites off the hand of Tom (Glenn Davis), Kev’s corrupt buddy. The tiger’s ghost then wanders the streets of Baghdad circa 2003, in the process rubbing shoulders with other ghosts, among them that of Uday Hussein, Saddam’s son (Hrach Titizian). In between these spectral encounters, we meet various other Iraqi citizens, all of whom are compromised to the degree that they have been forced to do business either with the Hussein family or the U.S. armed forces. We are, in short, in the shadowy land of moral equivalence, that mysterious domain where God is dead, life is absurd and everyone is no damn good.

Mr. Williams’ tiger is a foul-mouthed comedian-predator who is shot to death by Kev (Brad Fleischer), a loutishly stupid American soldier, when he bites off the hand of Tom (Glenn Davis), Kev’s corrupt buddy. The tiger’s ghost then wanders the streets of Baghdad circa 2003, in the process rubbing shoulders with other ghosts, among them that of Uday Hussein, Saddam’s son (Hrach Titizian). In between these spectral encounters, we meet various other Iraqi citizens, all of whom are compromised to the degree that they have been forced to do business either with the Hussein family or the U.S. armed forces. We are, in short, in the shadowy land of moral equivalence, that mysterious domain where God is dead, life is absurd and everyone is no damn good.

Might it be possible to write a first-rate play about the war in Iraq that proceeds from these assumptions? Absolutely. The animating premise of “Bengal Tiger in the Baghdad Zoo” is clever enough, and the script is structured skillfully. The trouble is that the play so rarely says anything unpredictable. It is, to be sure, a trifle unexpected that Uday should be unapologetically portrayed as a slick, Westernized monster of the will who tortures and kills because he feels like it. But to make both soldiers cartoonish Ugly Americans is too easy by half…

Mr. Williams’ performance is equally predictable, but it’s not his fault, for he’s playing the tiger as written: The script calls for a superficial Hollywood-style performance, and he obliges…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

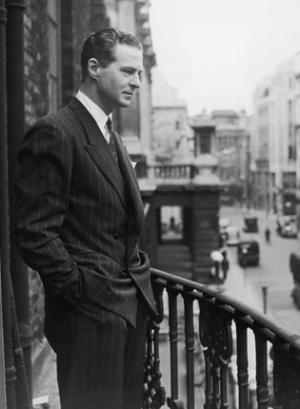

TT: The other centenarian

In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal I pay tribute to Terence Rattigan, a major twentieth-century playwright whose work is now virtually unknown in the United States. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Tennessee Williams was born a hundred years ago last week, and if there haven’t been many celebrations, it’s because they aren’t necessary. His best plays are performed regularly throughout America, and he is universally regarded as one of our greatest writers. But 2011 is also the centenary of Terence Rattigan’s birth, yet you’d be hard pressed to find anyone on this side of the Atlantic who is aware of the fact. Indeed, few American theatergoers are likely even to recognize Rattigan’s name, much less to know that the author of “Separate Tables” and “The Winslow Boy” was one of the 20th century’s most popular and successful playwrights. I’ve written scarcely a word about him in this paper’s drama column. Why? Because none of his two dozen plays, so far as I know, has received a major professional production in the U.S. since I became the Journal’s theater critic in 2003….

Why did Rattigan drop off the scope? Because he specialized in stylish, “well-made” plays about the English middle class and its deceptively genteel discontents. “I believe that the best plays are about people and not about things.” Rattigan wrote in 1950, and back then most people agreed with him. Starting in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a new generation of politically conscious playwrights like John Osborne and Shelagh Delaney started writing harsh portrayals of life on the wrong side of the tracks, and within a matter of years the determinedly apolitical Rattigan had become a period piece. But now that the “swinging ’60s” have themselves passed into history, it’s possible once again for English playgoers to unapologetically savor his sharp wit and elegant craftsmanship.

Why did Rattigan drop off the scope? Because he specialized in stylish, “well-made” plays about the English middle class and its deceptively genteel discontents. “I believe that the best plays are about people and not about things.” Rattigan wrote in 1950, and back then most people agreed with him. Starting in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a new generation of politically conscious playwrights like John Osborne and Shelagh Delaney started writing harsh portrayals of life on the wrong side of the tracks, and within a matter of years the determinedly apolitical Rattigan had become a period piece. But now that the “swinging ’60s” have themselves passed into history, it’s possible once again for English playgoers to unapologetically savor his sharp wit and elegant craftsmanship.

What is harder to say is whether Rattigan’s plays have any chance of finding an audience in the U.S. The problem is that virtually all of his best work is permeated with two quintessentially English themes that are unusually difficult for American actors and directors to understand: class differences and emotional inhibition. In a Rattigan play, you never have to ask where a character went to school or what he does for a living. You can tell by his accent–or his tie….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A scene from the 1951 film version of Rattigan’s The Browning Version, starring Michael Redgrave:

TT: Almanac

“Do you know what ‘le vice Anglais‘–the English vice–really is? Not flagellation, not pederasty–whatever the French believe it to be. It’s our refusal to admit our emotions. We think they demean us, I suppose.”

Terence Rattigan, In Praise of Love