It’s back to business as usual on Broadway: I do the job on Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo in today’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

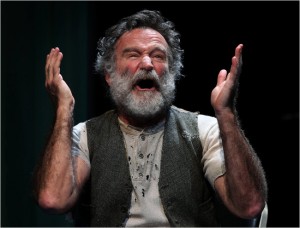

If you’re a movie star, you can do pretty much anything you want on Broadway. You can make your stage debut there, regardless of whether you’ve ever performed in front of an audience. You can be the leading man in a musical, despite the pesky fact that you’ve never sung anywhere but in your shower. You can even finagle a bunch of producers into putting up the cash to mount an ostensibly serious new play, the kind that normally wouldn’t have a chance of opening anywhere near Times Square. Which explains the unlikely presence on Broadway of Rajiv Joseph’s “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo,” a symbolic drama about the horrors of the war in Iraq that has just transferred to New York from the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Los Angeles with a single cast change: Robin Williams is making his Broadway debut in the title role….

Mr. Williams’ tiger is a foul-mouthed comedian-predator who is shot to death by Kev (Brad Fleischer), a loutishly stupid American soldier, when he bites off the hand of Tom (Glenn Davis), Kev’s corrupt buddy. The tiger’s ghost then wanders the streets of Baghdad circa 2003, in the process rubbing shoulders with other ghosts, among them that of Uday Hussein, Saddam’s son (Hrach Titizian). In between these spectral encounters, we meet various other Iraqi citizens, all of whom are compromised to the degree that they have been forced to do business either with the Hussein family or the U.S. armed forces. We are, in short, in the shadowy land of moral equivalence, that mysterious domain where God is dead, life is absurd and everyone is no damn good.

Mr. Williams’ tiger is a foul-mouthed comedian-predator who is shot to death by Kev (Brad Fleischer), a loutishly stupid American soldier, when he bites off the hand of Tom (Glenn Davis), Kev’s corrupt buddy. The tiger’s ghost then wanders the streets of Baghdad circa 2003, in the process rubbing shoulders with other ghosts, among them that of Uday Hussein, Saddam’s son (Hrach Titizian). In between these spectral encounters, we meet various other Iraqi citizens, all of whom are compromised to the degree that they have been forced to do business either with the Hussein family or the U.S. armed forces. We are, in short, in the shadowy land of moral equivalence, that mysterious domain where God is dead, life is absurd and everyone is no damn good.

Might it be possible to write a first-rate play about the war in Iraq that proceeds from these assumptions? Absolutely. The animating premise of “Bengal Tiger in the Baghdad Zoo” is clever enough, and the script is structured skillfully. The trouble is that the play so rarely says anything unpredictable. It is, to be sure, a trifle unexpected that Uday should be unapologetically portrayed as a slick, Westernized monster of the will who tortures and kills because he feels like it. But to make both soldiers cartoonish Ugly Americans is too easy by half…

Mr. Williams’ performance is equally predictable, but it’s not his fault, for he’s playing the tiger as written: The script calls for a superficial Hollywood-style performance, and he obliges…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Archives for April 1, 2011

TT: The other centenarian

In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal I pay tribute to Terence Rattigan, a major twentieth-century playwright whose work is now virtually unknown in the United States. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

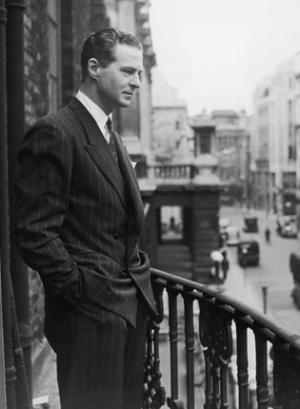

Tennessee Williams was born a hundred years ago last week, and if there haven’t been many celebrations, it’s because they aren’t necessary. His best plays are performed regularly throughout America, and he is universally regarded as one of our greatest writers. But 2011 is also the centenary of Terence Rattigan’s birth, yet you’d be hard pressed to find anyone on this side of the Atlantic who is aware of the fact. Indeed, few American theatergoers are likely even to recognize Rattigan’s name, much less to know that the author of “Separate Tables” and “The Winslow Boy” was one of the 20th century’s most popular and successful playwrights. I’ve written scarcely a word about him in this paper’s drama column. Why? Because none of his two dozen plays, so far as I know, has received a major professional production in the U.S. since I became the Journal’s theater critic in 2003….

Why did Rattigan drop off the scope? Because he specialized in stylish, “well-made” plays about the English middle class and its deceptively genteel discontents. “I believe that the best plays are about people and not about things.” Rattigan wrote in 1950, and back then most people agreed with him. Starting in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a new generation of politically conscious playwrights like John Osborne and Shelagh Delaney started writing harsh portrayals of life on the wrong side of the tracks, and within a matter of years the determinedly apolitical Rattigan had become a period piece. But now that the “swinging ’60s” have themselves passed into history, it’s possible once again for English playgoers to unapologetically savor his sharp wit and elegant craftsmanship.

Why did Rattigan drop off the scope? Because he specialized in stylish, “well-made” plays about the English middle class and its deceptively genteel discontents. “I believe that the best plays are about people and not about things.” Rattigan wrote in 1950, and back then most people agreed with him. Starting in the late ’50s and early ’60s, a new generation of politically conscious playwrights like John Osborne and Shelagh Delaney started writing harsh portrayals of life on the wrong side of the tracks, and within a matter of years the determinedly apolitical Rattigan had become a period piece. But now that the “swinging ’60s” have themselves passed into history, it’s possible once again for English playgoers to unapologetically savor his sharp wit and elegant craftsmanship.

What is harder to say is whether Rattigan’s plays have any chance of finding an audience in the U.S. The problem is that virtually all of his best work is permeated with two quintessentially English themes that are unusually difficult for American actors and directors to understand: class differences and emotional inhibition. In a Rattigan play, you never have to ask where a character went to school or what he does for a living. You can tell by his accent–or his tie….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A scene from the 1951 film version of Rattigan’s The Browning Version, starring Michael Redgrave:

TT: Almanac

“Do you know what ‘le vice Anglais‘–the English vice–really is? Not flagellation, not pederasty–whatever the French believe it to be. It’s our refusal to admit our emotions. We think they demean us, I suppose.”

Terence Rattigan, In Praise of Love