“Poets tend to be poor lyricists because their verse has its own inner music and doesn’t make allowance for the real thing.”

Stephen Sondheim, Finishing the Hat

Archives for March 2011

TT: Countdown

My latest stint as a visiting scholar at Rollins College’s Winter Park Institute ends on Friday, after which I return to New York and resume my regular life. Not surprisingly, my schedule in Florida has grown more and more hectic in recent days, so much so that simply to write about it makes my head sizzle.

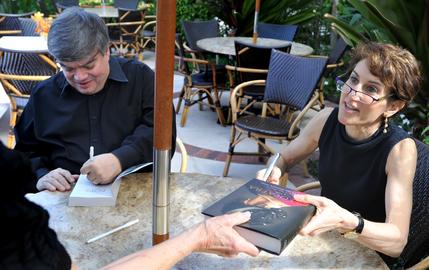

Among other things, I drove down to Palm Beach twice. On my first visit, I (A) took part in the world premiere of Steven Caras: See Them Dance and (B) spoke about and signed copies of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong at a breakfast that got written up in the local paper. A week later I went back to cover the opening of the regional premiere of Michael Hollinger’s Ghost-Writer. In between these two visits, I flew up to New York to see two Broadway shows and present a literary award on behalf of Barnes & Noble.

Among other things, I drove down to Palm Beach twice. On my first visit, I (A) took part in the world premiere of Steven Caras: See Them Dance and (B) spoke about and signed copies of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong at a breakfast that got written up in the local paper. A week later I went back to cover the opening of the regional premiere of Michael Hollinger’s Ghost-Writer. In between these two visits, I flew up to New York to see two Broadway shows and present a literary award on behalf of Barnes & Noble.

Here’s part of the official account of the latter occasion:

Barnes & Noble Inc., the world’s largest bookseller, today announced that Canadian Kim Echlin’s nostalgic novel of a cross-cultural love story, The Disappeared (Black Cat), and attorney David R. Dow’s spellbinding account of his efforts to defend the seemingly indefensible, The Autobiography of an Execution (Twelve), have been named the winners of the 2010 Discover Awards for fiction and non-fiction, respectively. Each writer was awarded a cash prize of $10,000, and a full year of marketing and merchandising support from the bookseller….

The non-fiction winner, The Autobiography of an Execution, is David R. Dow’s thrilling account of his efforts to give death row inmates a proper defense in a criminal justice system gone awry. Non-fiction jurist Terry Teachout said, “No matter how you feel about capital punishment–and especially if you support it, whether staunchly or uneasily–this book will bring you face to face with the arbitrary, often capricious way in which the death penalty really works. It’s the most sobering book that I read in 2010.”

Writers on the non-fiction jury panel included Eric Blehm, whose book, The Last Season, won the Discover Award in 2006; British journalist Christina Lamb, whose book, The Sewing Circles of Herat: A Personal Voyage Through Afghanistan, was a finalist for the Discover Award in 2002; and critic Terry Teachout, whose biographies include The Skeptic: A Life of H.L. Mencken and Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong.

The Discover Awards honor the works of exceptionally talented writers featured in the Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” program during the previous calendar year. In 2010, the Discover Great New Writers program featured the work of 60 previously unknown fiction and non-fiction writers….

I gave the prize to Dow at a luncheon ceremony on Wednesday and said a few heartfelt words about his book, which I once again commend to your attention.

From there I flew back down to Winter Park to attend a salon at which David Behrman, Diana Cooper, and Victoria Redel, the three master artists currently in residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, discussed their work with a group of local supporters of the center, which is the best-run and most handsomely designed artists’ colony imaginable. I paid a brief visit there last month, which had the effect of making me want to go back as soon as possible. (Small-world story: Behrman turns out to be the son of S.N. Behrman, the playwright whose work is a cause of mine. He was as surprised to learn that I knew who his father was as I was to learn that he was Sam Behrman’s son.)

From there I flew back down to Winter Park to attend a salon at which David Behrman, Diana Cooper, and Victoria Redel, the three master artists currently in residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, discussed their work with a group of local supporters of the center, which is the best-run and most handsomely designed artists’ colony imaginable. I paid a brief visit there last month, which had the effect of making me want to go back as soon as possible. (Small-world story: Behrman turns out to be the son of S.N. Behrman, the playwright whose work is a cause of mine. He was as surprised to learn that I knew who his father was as I was to learn that he was Sam Behrman’s son.)

Next came my second trip to Palm Beach, after which I returned to Winter Park to write a review of one of the shows I’d seen on Broadway (it’ll be in Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal) and hear a performance of Bach’s St. John Passion given by the Bach Festival Society that was conducted by my old friend John Sinclair. Having just spent a week hurtling from place to place, it was a comfort to sit in Rollins College’s Knowles Memorial Chapel, one of the most tranquil spaces that I know, and listen to profoundly spiritual music that says what it has to say without wasting a note.

Next came my second trip to Palm Beach, after which I returned to Winter Park to write a review of one of the shows I’d seen on Broadway (it’ll be in Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal) and hear a performance of Bach’s St. John Passion given by the Bach Festival Society that was conducted by my old friend John Sinclair. Having just spent a week hurtling from place to place, it was a comfort to sit in Rollins College’s Knowles Memorial Chapel, one of the most tranquil spaces that I know, and listen to profoundly spiritual music that says what it has to say without wasting a note.

Now my work in Florida is done, and all that remains for Mrs. T and me to do is pack our bags and say goodbye to our new friends. Have we missed New York? Sure. In fact, we’ve been on the move so steadily since mid-December that we haven’t even had time to buy furniture for our new Manhattan apartment, much less to hang any of the pieces in the Teachout Museum. I long to explore our new neighborhood, and I want very much to see all my old friends in New York.

That said, I also know that come Friday night, I’ll be missing Winter Park, too. Aside from the straightforward and uncomplicated affection that I feel for the place and its people, I’m astonished by the amount of work that I’ve been able to get done on Danse Russe, Satchmo at the Waldorf, and my Duke Ellington biography since I arrived here in January. New York, they say, is the most stimulating of cities, but I find there’s at least as much to be said for the beneficial effects of setting up shop in a smaller, quieter place where the pace is slower and the overall frenzy level significantly lower (though not in the past couple of weeks!).

In 1991 I wrote a book in which I asked the following question: “When do we acquire the grace to feel at home where we are?” Home, needless to say, is wherever Mrs. T is, but otherwise…well, I’m still working on that one twenty years later.

TT: Just because

An extremely rare kinescope of film noir actress Lizabeth Scott singing “He Is a Man” on TV in 1958:

TT: Almanac

“One of the jobs of poetry is to make the unbearable bearable, not by falsehood but by clear, precise confrontation.”

Richard Wilbur, interview, The Paris Review, Winter 1977

TT: Imitation of life

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the premiere of David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People, which I didn’t like at all. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Good People” is, or purports to be, a study of life in Southie, a down-at-heel Boston neighborhood beloved of movie stars who think they can do the local accent. Mr. Lindsay-Abaire, who comes from a real-life Southie family, managed to land a scholarship to a tony New England prep school, which was his escalator to fame and fortune. All this undoubtedly explains the plot of “Good People,” in which Margie (Frances McDormand, who works the charm pedal a bit too enthusiastically) is fired from her job as a clerk at a local dollar store, thus making it impossible for her to support her adult daughter, who was born prematurely and is severely handicapped (and who is kept offstage throughout the play, presumably so as not to shock the matinée crowd). In desperation, Margie looks up Mikey (Tate Donovan), an old high-school boyfriend who studied hard, became a doctor and now lives in a big house in a fancy suburb with his cute young wife (Renée Elise Goldsberry), who is–wait for it–an upper-middle-class black.

In the first scene, we see Margie being canned for chronic lateness. Needless to say, it’s not her fault: She has babysitter problems. Indeed, her only flaw is an endearing one, which is that she can’t stop herself from saying what she thinks at any given moment, no matter how ill-timed it may be. Otherwise, she’s a basically good person, and that brings us to the moral of the play, which is that bad things happen to good people–and vice versa. Take Mikey, who believes that his success is his own doing and not a matter of luck, a conviction that has made him resentful and guilt-ridden, two qualities that manifest themselves in his willingness to treat Margie like dirt.

In the first scene, we see Margie being canned for chronic lateness. Needless to say, it’s not her fault: She has babysitter problems. Indeed, her only flaw is an endearing one, which is that she can’t stop herself from saying what she thinks at any given moment, no matter how ill-timed it may be. Otherwise, she’s a basically good person, and that brings us to the moral of the play, which is that bad things happen to good people–and vice versa. Take Mikey, who believes that his success is his own doing and not a matter of luck, a conviction that has made him resentful and guilt-ridden, two qualities that manifest themselves in his willingness to treat Margie like dirt.

Herein lies part of the phoniness of “Good People.” Of course people like Margie and Mikey exist, but I doubt it’s a coincidence that they are exactly the kinds of people who fit into the familiar sociological narrative that permeates every page of this play. In Mr. Lindsay-Abaire’s America, success is purely a matter of luck, and virtue inheres solely in those who are luckless. So what if Mikey worked hard? Why should anybody deserve any credit for working hard? Hence the crude deck-stacking built into the script of “Good People,” in which Mikey is the callous villain who forgot where he came from and Margie the plucky Southie gal who may be the least little bit racist (though she never says anything nasty to Mikey’s wife–that would be going too far!) but is otherwise a perfect heroine-victim.

No less phony, though, is the fact that “Good People” plays like a comedy, not a tragedy. For all their grinding poverty, Margie and her Southie friends are incapable of uttering two consecutive lines without tossing in a snappy comeback….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Turn on, tune in, get serious

In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal, I take note of a very important pair of high-culture home video releases, Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus and John Gielgud: Ages of Man. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

In the fledgling years of network TV, Sunday mornings and afternoons were reserved for serious news shows like Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now” and high-culture programs of various kinds, a practice so universally accepted that those time slots were collectively known to grumbling journalists as the “cultural ghetto.” Little did the grumblers know that a half-century later, the fine arts would have all but vanished from the commercial networks–and would be increasingly hard to find on PBS, the non-commercial network that was originally founded in part to give high culture a safe haven.

I cut my artistic teeth watching TV on Sundays, and now that some of the long-lost programs of my youth have finally made their way to DVD, I find myself astonished by what ABC, CBS and NBC were willing to telecast all those years ago. For those who know PBS as the home of Lawrence Welk reruns and A&E as the network of “Dog the Bounty Hunter,” I recommend a pair of releases from E1 Home Video, “Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus” and “John Gielgud: Ages of Man.” Between them, they’ll open your eyes to the unlimited possibilities of TV as a force for cultural good–and fill you with despair at the fact that such high-minded programming has largely disappeared from the small screen.

I cut my artistic teeth watching TV on Sundays, and now that some of the long-lost programs of my youth have finally made their way to DVD, I find myself astonished by what ABC, CBS and NBC were willing to telecast all those years ago. For those who know PBS as the home of Lawrence Welk reruns and A&E as the network of “Dog the Bounty Hunter,” I recommend a pair of releases from E1 Home Video, “Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus” and “John Gielgud: Ages of Man.” Between them, they’ll open your eyes to the unlimited possibilities of TV as a force for cultural good–and fill you with despair at the fact that such high-minded programming has largely disappeared from the small screen.

“Omnibus” was a cultural TV magazine underwritten by the Ford Foundation that shuttled among the three networks in the ’50s. Hosted by Alistair Cooke, it offered viewers glimpses of everything from Orson Welles’ “King Lear” to Mike Nichols and Elaine May, but it is best remembered by historians of American music for having introduced Leonard Bernstein to TV audiences. Unlike his later “Young People’s Concerts,” Bernstein’s seven “Omnibus” shows were made specifically for adult viewers, and they used the medium in a way that remains electrifyingly fresh to this day….

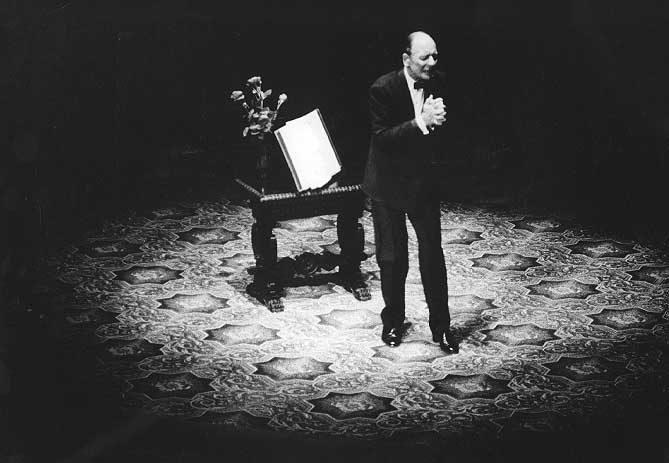

If anything, “Ages of Man” is more remarkable still, consisting as it does of a hundred-minute program in which the most admired classical actor of the 20th century, standing alone on a near-bare stage in a business suit, does nothing whatsoever but recite and talk about sonnets by and excerpts from the plays of William Shakespeare. Gielgud had performed this one-man show around the world between 1957 and 1966, when he brought its phenomenally successful run to a close by filming it for CBS. The black-and-white telecast, directed by Paul Bogart, is as devoid of high-tech gimmickry as a slab of rare roast beef: Virtually all of the show is shot in close-up, and Gielgud’s comments are as unobtrusive as the dirt-plain set. Yet it is precisely because of this simplicity that “Ages of Man” is so priceless…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” Leonard Bernstein’s first Omnibus telecast:

TT: Almanac

“The basic stimulus to the intelligence is doubt, a feeling that the meaning of an experience is not self-evident.”

W.H. Auden, “The Protestant Mystics”

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• La Cage aux Folles (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Driving Miss Daisy * (drama, G, possible for smart children, closes Apr. 9, reviewed here)

• The Importance of Being Earnest (high comedy, G, just possible for very smart children, closes July 3, reviewed here)

• Lombardi (drama, G/PG-13, a modest amount of adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Million Dollar Quartet (jukebox musical, G, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Angels in America (drama, PG-13/R, adult subject matter, extended through Apr. 24, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Molly Sweeney (drama, G, too serious for children, extended through Apr. 10, reviewed here)

• Play Dead (theatrical spook show, PG-13, utterly unsuitable for easily frightened children or adults, reviewed here)

IN WASHINGTON, D.C.:

• Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (drama, PG-13/R, Washington remounting of Chicago production, adult subject matter, closes Apr. 10, Chicago run reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• Black Tie (comedy, PG-13, closes Mar. 27, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN SARASOTA, FLA.:

• Twelve Angry Men (drama, G, closes Mar. 26, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN ORLANDO, FLA.:

• A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Pride and Prejudice (comedy, G, playing in rotating repertory through Mar. 19-20, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN MINNEAPOLIS:

• Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (drama, PG-13/R, Minneapolis remounting of Phoenix production, adult subject matter and violence, Phoenix run reviewed here)