In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the premiere of David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People, which I didn’t like at all. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Good People” is, or purports to be, a study of life in Southie, a down-at-heel Boston neighborhood beloved of movie stars who think they can do the local accent. Mr. Lindsay-Abaire, who comes from a real-life Southie family, managed to land a scholarship to a tony New England prep school, which was his escalator to fame and fortune. All this undoubtedly explains the plot of “Good People,” in which Margie (Frances McDormand, who works the charm pedal a bit too enthusiastically) is fired from her job as a clerk at a local dollar store, thus making it impossible for her to support her adult daughter, who was born prematurely and is severely handicapped (and who is kept offstage throughout the play, presumably so as not to shock the matinée crowd). In desperation, Margie looks up Mikey (Tate Donovan), an old high-school boyfriend who studied hard, became a doctor and now lives in a big house in a fancy suburb with his cute young wife (Renée Elise Goldsberry), who is–wait for it–an upper-middle-class black.

In the first scene, we see Margie being canned for chronic lateness. Needless to say, it’s not her fault: She has babysitter problems. Indeed, her only flaw is an endearing one, which is that she can’t stop herself from saying what she thinks at any given moment, no matter how ill-timed it may be. Otherwise, she’s a basically good person, and that brings us to the moral of the play, which is that bad things happen to good people–and vice versa. Take Mikey, who believes that his success is his own doing and not a matter of luck, a conviction that has made him resentful and guilt-ridden, two qualities that manifest themselves in his willingness to treat Margie like dirt.

In the first scene, we see Margie being canned for chronic lateness. Needless to say, it’s not her fault: She has babysitter problems. Indeed, her only flaw is an endearing one, which is that she can’t stop herself from saying what she thinks at any given moment, no matter how ill-timed it may be. Otherwise, she’s a basically good person, and that brings us to the moral of the play, which is that bad things happen to good people–and vice versa. Take Mikey, who believes that his success is his own doing and not a matter of luck, a conviction that has made him resentful and guilt-ridden, two qualities that manifest themselves in his willingness to treat Margie like dirt.

Herein lies part of the phoniness of “Good People.” Of course people like Margie and Mikey exist, but I doubt it’s a coincidence that they are exactly the kinds of people who fit into the familiar sociological narrative that permeates every page of this play. In Mr. Lindsay-Abaire’s America, success is purely a matter of luck, and virtue inheres solely in those who are luckless. So what if Mikey worked hard? Why should anybody deserve any credit for working hard? Hence the crude deck-stacking built into the script of “Good People,” in which Mikey is the callous villain who forgot where he came from and Margie the plucky Southie gal who may be the least little bit racist (though she never says anything nasty to Mikey’s wife–that would be going too far!) but is otherwise a perfect heroine-victim.

No less phony, though, is the fact that “Good People” plays like a comedy, not a tragedy. For all their grinding poverty, Margie and her Southie friends are incapable of uttering two consecutive lines without tossing in a snappy comeback….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Archives for March 4, 2011

TT: Turn on, tune in, get serious

In my “Sightings” column for today’s Wall Street Journal, I take note of a very important pair of high-culture home video releases, Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus and John Gielgud: Ages of Man. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

In the fledgling years of network TV, Sunday mornings and afternoons were reserved for serious news shows like Edward R. Murrow’s “See It Now” and high-culture programs of various kinds, a practice so universally accepted that those time slots were collectively known to grumbling journalists as the “cultural ghetto.” Little did the grumblers know that a half-century later, the fine arts would have all but vanished from the commercial networks–and would be increasingly hard to find on PBS, the non-commercial network that was originally founded in part to give high culture a safe haven.

I cut my artistic teeth watching TV on Sundays, and now that some of the long-lost programs of my youth have finally made their way to DVD, I find myself astonished by what ABC, CBS and NBC were willing to telecast all those years ago. For those who know PBS as the home of Lawrence Welk reruns and A&E as the network of “Dog the Bounty Hunter,” I recommend a pair of releases from E1 Home Video, “Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus” and “John Gielgud: Ages of Man.” Between them, they’ll open your eyes to the unlimited possibilities of TV as a force for cultural good–and fill you with despair at the fact that such high-minded programming has largely disappeared from the small screen.

I cut my artistic teeth watching TV on Sundays, and now that some of the long-lost programs of my youth have finally made their way to DVD, I find myself astonished by what ABC, CBS and NBC were willing to telecast all those years ago. For those who know PBS as the home of Lawrence Welk reruns and A&E as the network of “Dog the Bounty Hunter,” I recommend a pair of releases from E1 Home Video, “Leonard Bernstein: Omnibus” and “John Gielgud: Ages of Man.” Between them, they’ll open your eyes to the unlimited possibilities of TV as a force for cultural good–and fill you with despair at the fact that such high-minded programming has largely disappeared from the small screen.

“Omnibus” was a cultural TV magazine underwritten by the Ford Foundation that shuttled among the three networks in the ’50s. Hosted by Alistair Cooke, it offered viewers glimpses of everything from Orson Welles’ “King Lear” to Mike Nichols and Elaine May, but it is best remembered by historians of American music for having introduced Leonard Bernstein to TV audiences. Unlike his later “Young People’s Concerts,” Bernstein’s seven “Omnibus” shows were made specifically for adult viewers, and they used the medium in a way that remains electrifyingly fresh to this day….

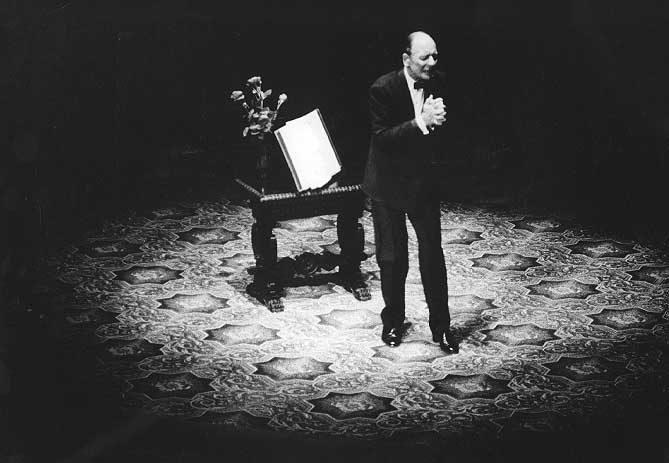

If anything, “Ages of Man” is more remarkable still, consisting as it does of a hundred-minute program in which the most admired classical actor of the 20th century, standing alone on a near-bare stage in a business suit, does nothing whatsoever but recite and talk about sonnets by and excerpts from the plays of William Shakespeare. Gielgud had performed this one-man show around the world between 1957 and 1966, when he brought its phenomenally successful run to a close by filming it for CBS. The black-and-white telecast, directed by Paul Bogart, is as devoid of high-tech gimmickry as a slab of rare roast beef: Virtually all of the show is shot in close-up, and Gielgud’s comments are as unobtrusive as the dirt-plain set. Yet it is precisely because of this simplicity that “Ages of Man” is so priceless…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from “Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony,” Leonard Bernstein’s first Omnibus telecast:

TT: Almanac

“The basic stimulus to the intelligence is doubt, a feeling that the meaning of an experience is not self-evident.”

W.H. Auden, “The Protestant Mystics”