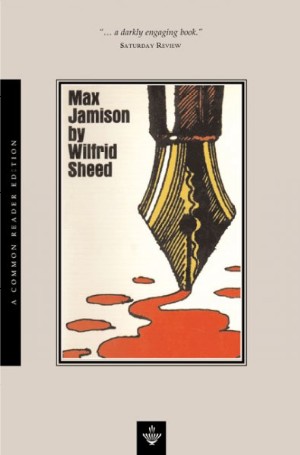

Wilfrid Sheed, who was (almost) as good a novelist as he was a critic, died two weeks ago. In his honor, I’ve devoted my “Sightings” column in today’s Wall Street Journal to his best novel, Max Jamison. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Never pay any attention to what critics say,” Jean Sibelius once told a fellow composer. “Remember, a statue has never been set up in honor of a critic!” The members of my unhallowed profession have, however, been portrayed in many novels, plays and movies, and most of those portrayals have been pretty nasty. From Addison DeWitt in “All About Eve” to Anton Ego in “Ratatouille,” fictional critics tend as a rule to be snide, venal and, above all all, creatively impotent. What’s more, you get the definite feeling that they loathe themselves for being unable to do that of which they write. As DeWitt puts it with self-lacerating hauteur, “My native habitat is the theater. In it I toil not, neither do I spin.”

I won’t say that these portrayals are totally unfair. (In fact, I won’t even say they’re mostly unfair, but that’s another column.) I do, however, want to draw your attention to a very different kind of portrait, one that was, logically enough, written by a very different kind of critic. Wilfrid Sheed, who died the other day, was a greatly talented novelist who ended up being better known as a critic, in which capacity he was also formidably gifted. But if there’s any justice in this world, Mr. Sheed will remembered longest for “Max Jamison,” the 1970 novel in which he brought off the seemingly impossible feat of making a drama critic look quite a bit like a human being.

I won’t say that these portrayals are totally unfair. (In fact, I won’t even say they’re mostly unfair, but that’s another column.) I do, however, want to draw your attention to a very different kind of portrait, one that was, logically enough, written by a very different kind of critic. Wilfrid Sheed, who died the other day, was a greatly talented novelist who ended up being better known as a critic, in which capacity he was also formidably gifted. But if there’s any justice in this world, Mr. Sheed will remembered longest for “Max Jamison,” the 1970 novel in which he brought off the seemingly impossible feat of making a drama critic look quite a bit like a human being.

The title character of “Max Jamison” is a New York critic with two strings to his bow. He writes about film for a highbrow quarterly and theater for Now, an imaginary weekly newsmagazine that bears a not-so-coincidental resemblance to Time (just as Max himself bears a surface resemblance to John Simon, though Mr. Sheed vehemently denied that Mr. Simon was his model). Max is, in his own words, “a son of a bitch in an imperfect world” who has grown weary of “the dreary business of accreting an opinion.” He is also desperately and comprehensively unhappy, having had two marriages blow up under him, and as the book begins, he is teetering on the edge of a full-blown midlife crisis, the kind where you chase after much younger women and hear poisonously snippy voices in the night.

Max is also–and this is the point of the novel–a man of impeccably cultivated taste who is tortured by the increasing tastelessness of the world around him, and who expresses his exasperation in one- and two-liners that go off in nearly every paragraph, leaving gaping holes wherever they explode….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog