Today’s Wall Street Journal is devoted in its entirety to a review of the new off-Broadway production of Three Sisters. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

In Ira Gershwin’s lyric for “But Not for Me,” a heartsick postmistress declares that love has brought her “more clouds of gray/Than any Russian play/Could guarantee.” If I had to guess, I’d say that the lady in question had “Three Sisters” in mind. Few plays are more depressing than Anton Chekhov’s soft-spoken study of a turn-of-the-century trio of provincial Russian women who long for the bright lights of Moscow but are forced to settle for ordinary small-town lives that bring them little in the way of joy. What makes their story endurable is the lightness of touch with which Chekhov tells it–which is also what makes it so agonizing to see their remaining hopes dissolve at play’s end.

The sisters’ tale is, of course, characteristically Russian in its jarringly close juxtaposition of comedy and heartbreak, and that is what poses the biggest difficulty to present-day interpreters: How do you make a play written in pre-revolutionary Russia in 1900 work in America in 2011? In the Classic Stage Company’s new Off-Broadway production, Austin Pendleton is taking the same tack that he took two years ago in that company’s “Uncle Vanya,” which is to toss a group of modern-sounding actors into a traditional-looking setting and see what happens. The results are once again interesting but very uneven, though not so much as to keep Chekhov’s great play from making its heart-breaking effect.

The sisters’ tale is, of course, characteristically Russian in its jarringly close juxtaposition of comedy and heartbreak, and that is what poses the biggest difficulty to present-day interpreters: How do you make a play written in pre-revolutionary Russia in 1900 work in America in 2011? In the Classic Stage Company’s new Off-Broadway production, Austin Pendleton is taking the same tack that he took two years ago in that company’s “Uncle Vanya,” which is to toss a group of modern-sounding actors into a traditional-looking setting and see what happens. The results are once again interesting but very uneven, though not so much as to keep Chekhov’s great play from making its heart-breaking effect.

Mr. Pendleton’s cast is full of familiar faces, some of whom also appeared in his “Uncle Vanya.” The sisters are Maggie Gyllenhaal, Jessica Hecht, and Juliet Rylance, and of them it is Ms. Rylance who is most memorable. Her warm, throaty alto and utterly sincere demeanor are just right for Irina, the youngest and least disillusioned of the three sisters. Ms. Hecht also gives a strong and believable performance as the careworn Olga. Not so Ms. Gyllenhaal, a talented performer who is as wrongly cast here as she was in “Uncle Vanya,” and for much the same reason: Her demeanor and voice are so obviously contemporary as to jolt the eye and ear….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Archives for February 4, 2011

TT: Neither does he spin

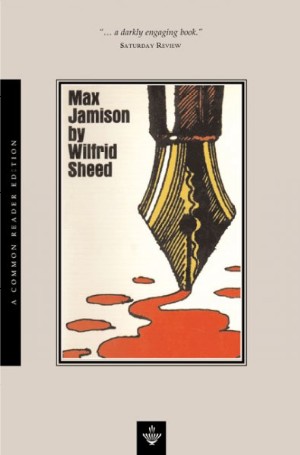

Wilfrid Sheed, who was (almost) as good a novelist as he was a critic, died two weeks ago. In his honor, I’ve devoted my “Sightings” column in today’s Wall Street Journal to his best novel, Max Jamison. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Never pay any attention to what critics say,” Jean Sibelius once told a fellow composer. “Remember, a statue has never been set up in honor of a critic!” The members of my unhallowed profession have, however, been portrayed in many novels, plays and movies, and most of those portrayals have been pretty nasty. From Addison DeWitt in “All About Eve” to Anton Ego in “Ratatouille,” fictional critics tend as a rule to be snide, venal and, above all all, creatively impotent. What’s more, you get the definite feeling that they loathe themselves for being unable to do that of which they write. As DeWitt puts it with self-lacerating hauteur, “My native habitat is the theater. In it I toil not, neither do I spin.”

I won’t say that these portrayals are totally unfair. (In fact, I won’t even say they’re mostly unfair, but that’s another column.) I do, however, want to draw your attention to a very different kind of portrait, one that was, logically enough, written by a very different kind of critic. Wilfrid Sheed, who died the other day, was a greatly talented novelist who ended up being better known as a critic, in which capacity he was also formidably gifted. But if there’s any justice in this world, Mr. Sheed will remembered longest for “Max Jamison,” the 1970 novel in which he brought off the seemingly impossible feat of making a drama critic look quite a bit like a human being.

I won’t say that these portrayals are totally unfair. (In fact, I won’t even say they’re mostly unfair, but that’s another column.) I do, however, want to draw your attention to a very different kind of portrait, one that was, logically enough, written by a very different kind of critic. Wilfrid Sheed, who died the other day, was a greatly talented novelist who ended up being better known as a critic, in which capacity he was also formidably gifted. But if there’s any justice in this world, Mr. Sheed will remembered longest for “Max Jamison,” the 1970 novel in which he brought off the seemingly impossible feat of making a drama critic look quite a bit like a human being.

The title character of “Max Jamison” is a New York critic with two strings to his bow. He writes about film for a highbrow quarterly and theater for Now, an imaginary weekly newsmagazine that bears a not-so-coincidental resemblance to Time (just as Max himself bears a surface resemblance to John Simon, though Mr. Sheed vehemently denied that Mr. Simon was his model). Max is, in his own words, “a son of a bitch in an imperfect world” who has grown weary of “the dreary business of accreting an opinion.” He is also desperately and comprehensively unhappy, having had two marriages blow up under him, and as the book begins, he is teetering on the edge of a full-blown midlife crisis, the kind where you chase after much younger women and hear poisonously snippy voices in the night.

Max is also–and this is the point of the novel–a man of impeccably cultivated taste who is tortured by the increasing tastelessness of the world around him, and who expresses his exasperation in one- and two-liners that go off in nearly every paragraph, leaving gaping holes wherever they explode….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken.”

C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves