Nothing has ever been too good for the public.

Nothing has ever been good enough for the public.

Orson Welles, undated memorandum, 1942

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Nothing has ever been too good for the public.

Nothing has ever been good enough for the public.

Orson Welles, undated memorandum, 1942

Webb Pierce sings “There Stands the Glass”:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

“I like music that is proud of itself.”

Bernard Herrmann (quoted in Steven Smith, A Heart at Fire’s Center)

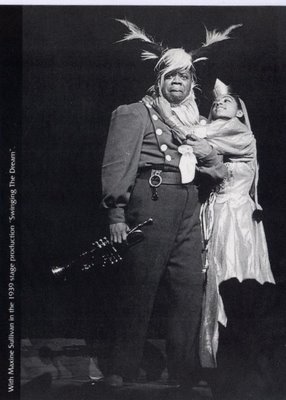

Believe it or not, I’m still giving speeches about Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, and my next one will take place on Thursday at the Mid-Manhattan branch of the New York Public Library. The address is 455 Fifth Avenue and the festivities get underway is six-thirty sharp.

Believe it or not, I’m still giving speeches about Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, and my next one will take place on Thursday at the Mid-Manhattan branch of the New York Public Library. The address is 455 Fifth Avenue and the festivities get underway is six-thirty sharp.

If you’ve somehow managed to miss my dog-and-pony show until now, it’s time to plug this yawning hole in your life–and to get your copy of Pops signed, assuming that you own one, no other assumption being possible. I do have one more Pops-related New York appearance set for Bryant Park on August 11, but why wait until then when you can see me now?

For more details, go here.

“Actors and directors are not, generally speaking, well qualified for any other job; most hit on their vocations precisely because they seemed no good for anything else. This is the moment at which character and power of endurance–what the Victorians used to call ‘bottom’–becomes almost as important as talent, and much more important than luck.”

Simon Callow, Orson Welles: Hello Americans

In the New York edition of today’s Wall Street Journal, I review The Bilbao Effect, Oren Safdie’s new play about the splendors and miseries of postmodern starchitecture. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Architecture is the only art form about which everybody has an opinion–because everybody has to live with it. Some buildings, however, are harder to live with than others, and in recent years a growing number of them have been the work of big-name “starchitects” who appear at times to be more interested in making a splash than ensuring the day-to-day livability of their buildings. Enter Oren Safdie, the son of the famous modernist architect Moshe Safdie, who in 2003 wrote a witty and knowing play called “Private Jokes, Public Places” in which he ran a sharp skewer through the pretensions of a generation of starchitects who give the impression of having forgotten that human beings live in and near the buildings they design….

Now Mr. Safdie is back at the Center for Architecture with a sequel, “The Bilbao Effect,” in which the principal characters from “Private Jokes, Public Places” return to the stage to conduct a furiously farcical debate over the wholly serious subject of the architect’s responsibility to the people whose lives he touches.

Now Mr. Safdie is back at the Center for Architecture with a sequel, “The Bilbao Effect,” in which the principal characters from “Private Jokes, Public Places” return to the stage to conduct a furiously farcical debate over the wholly serious subject of the architect’s responsibility to the people whose lives he touches.

The play’s title is, of course, a nod to Frank Gehry’s 1997 branch of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, an avant-garde building so self-consciously spectacular that it has become a tourist attraction in its own right. Its success persuading other institutions to undertake the construction of equally over-the-top structures in the hopes of drawing visitors whose spending will galvanize the local economy and enhance their own bottom lines. In “The Bilbao Effect,” Mr. Safdie imagines that Staten Island’s city fathers have succumbed to a similar case of architectural hubris and allowed the egomaniacal Erhardt Shlaminger (Joris Stuyck) of “Private Jokes, Public Places” to build a Gehry-like urban-renewal project in the middle of town….

Good plays of ideas allow the audience to make up its own mind about the relative merits of the characters’ arguments. One of the best things about “Private Jokes, Public Places” was Mr. Safdie’s willingness to let everyone look stupid at one time or another, whereas in “The Bilbao Effect” Schlaminger and his smug lawyer (John Bolton) are too obviously the villains of the piece.

All this notwithstanding, “The Bilbao Effect” is both funny and cruelly smart in its portrayal of the lunatic excesses of the more extreme varieties of starchitecture. Perhaps the shrewdest of Mr. Safdie’s touches is the way in which he conceives of the debate over such architecture as a class war…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

As some of you are aware, my recent visit to Chicago was a bit on the stressful side. Mrs. T was laid low with gallstones a week ago, thus necessitating an emergency-room visit and a stay at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. We are immensely grateful to the staffs of both Northwestern and the Hyatt Regency, who knew exactly what to do when I called the switchboard at two a.m. and asked for the address of the nearest hospital.

We returned to the East Coast last Friday on schedule, and Mrs. T is now resting more or less comfortably up in Connecticut as we wait for her doctors there to decide what they want to do next. I’ll keep you posted.

“He had crashed through the barrier. He had stopped worrying and started relaxing. He was up on that plateau where you just did whatever needed doing. I knew that place. I lived there.”

Lee Child, Killing Floor

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog