“I live in a house that was quite modern for its time, in a neighborhood that broke with the grid and tried to bring new ideas to the standard city model. I love most architecture that tried to do something different, right up until the point where the expression of one individual became the only thing that mattered. Architecture has always been a collaboration–even if there’s one Genius designing the building, he or she collaborates with the developers, the occupants, and the street where the building exists. Now we have enormous mounds of narcissistic concrete and metal, housing the yawps and shouts of artists who cannot put the past into the shredder fast enough.

“I hate feeling this way.”

James Lileks, The Bleat, July 7, 2010

Archives for 2010

DANCE

Pilobolus Dance Theatre (Joyce Theater, 175 Eighth Ave., closes Aug. 7). These are hard times for the much-loved modern dance troupe, which is coming to grips with the recent death of Jonathan Wolken, one of its founding members. Yet there can be no better way to celebrate Wolken’s life than to pay a visit to Pilobolus’ annual summer season at the Joyce Theater. The company is performing three mixed bills, the first of which features the New York premiere of Hapless Hooligan in “Still Moving,” a collaboration with Art Spiegelman. No matter which one you see, you’ll be entranced (TT).

BOOK

Brooke Berman, No Place Like Home: A Memoir in 39 Apartments (Harmony, $23). The author of Hunting and Gathering came to Manhattan at the age of eighteen in the hopes of someday becoming a full-time professional playwright. Talented, inexperienced, naïve, and broke, she spent the next twenty years sharing microscopically small apartments, sleeping on futons, bouncing from roommate to roommate and gradually finding herself along the way. Now she’s written a memoir of her formative years, and it’s a lovely piece of work, at once charming and deeply felt. No Place Like Home is one of the best books I’ve read about how young artists make their way–or not–in an unforgiving world (TT).

TT: Two kings make a winning hand

I spent the week in San Diego seeing The Madness of George III and King Lear, two of the three shows currently being performed in rotating repertory as part of the Old Globe’s 2010 Shakespeare Festival. They make a nifty pair. Here’s an excerpt from my Wall Street Journal review.

* * *

Some plays, including most of the best ones, are all but impossible to film, but a handful of memorable stage shows have been filmed so well as to discourage subsequent revivals. Nicholas Hytner’s 1994 film of Alan Bennett’s “The Madness of George III” is a case in point, for it was so effective that productions of the play in this country have since been few and far between. That’s what lured me to San Diego to see the Old Globe’s outdoor version, directed by Adrian Noble as part of the company’s 2010 Shakespeare Festival. It appears to be the play’s first American staging of any consequence since the National Theater’s production (on which Mr. Hytner’s film was based) toured the U.S. in 1993. All praise to the Old Globe for mounting it so stylishly–and proving that fine though it was on screen, “The Madness of George III” is even better on stage.

Some plays, including most of the best ones, are all but impossible to film, but a handful of memorable stage shows have been filmed so well as to discourage subsequent revivals. Nicholas Hytner’s 1994 film of Alan Bennett’s “The Madness of George III” is a case in point, for it was so effective that productions of the play in this country have since been few and far between. That’s what lured me to San Diego to see the Old Globe’s outdoor version, directed by Adrian Noble as part of the company’s 2010 Shakespeare Festival. It appears to be the play’s first American staging of any consequence since the National Theater’s production (on which Mr. Hytner’s film was based) toured the U.S. in 1993. All praise to the Old Globe for mounting it so stylishly–and proving that fine though it was on screen, “The Madness of George III” is even better on stage.

If you haven’t seen it in either form, here’s a quick refresher course in 18th-century British history: King George III (played at the Old Globe by Miles Anderson) was stricken in 1788 with a mental disorder that left him incapacitated and triggered a political crisis. Seeing a chance to force William Pitt, the Tory prime minister, out of office, Charles James Fox, the leader of the Whig opposition, sought to ram a bill through Parliament authorizing the Prince of Wales to act as Prince Regent and replace Pitt with Fox. It was only when Dr. Francis Willis succeeded against all odds in restoring the king to his senses that the regency was forestalled and the crisis defused.

Out of these grim events, Mr. Bennett has spun a sparkling play whose sober subject is the corrupting effect of power on those who attain it–and, by extension, the corrupting effect of the British class system on those who profit from its privileges….

The Old Globe has fielded a cast of 26 for “The Madness of George III,” which is another reason why the play has all but vanished from the stage: Few American companies can now afford to put on so labor-intensive a show. To perform it in rotating repertory with “King Lear,” also directed by Mr. Noble, is a feat still further beyond the reach of most regional theater companies, but the Old Globe is bringing it off with seeming effortlessness–and throwing in “The Taming of the Shrew” for good measure! I’ve seen two other productions “Shrews” in recent weeks, so I passed this one up, but the Old Globe’s “Lear” is a splendid piece of work that no one in or near southern California should miss.

What is most surprising about Mr. Noble’s “Lear” is his unexpected avoidance of the grand manner. His program note, in which he speaks of presenting the play in a “language-based” style that embraces “the American accent and cadence of speech,” gives the clue: This is a text-driven, eloquently plain-spoken “Lear” that strives at all times to be clear and comprehensible, leaving the heavy lifting to Shakespeare instead of trying to do it for him….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

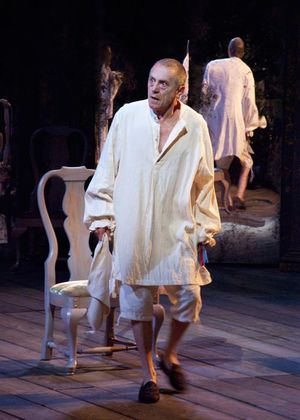

A scene from The Madness of King George, Nicholas Hytner’s 1994 film version of The Madness of George III:

TT: Almanac

“If forty million people say a foolish thing it does not become a wise one, but the wise man is foolish to give them the lie.”

W. Somerset Maugham, A Writer’s Notebook

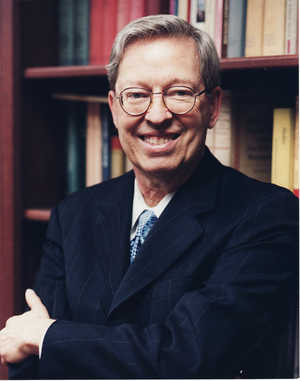

TT: Richard Harriman, R.I.P.

William Jewell College, my alma mater, is the home of one of the finest performing-arts series in America, the Harriman-Jewell Series. Among countless noteworthy things, the Harriman-Jewell Series presented Luciano Pavarotti in his professional recital debut in 1973. During my student days, I saw under its auspices performances by Pavarotti, Birgit Nilsson, Itzhak Perlman, Leontyne Price, Mstislav Rostropovich, Rudolf Serkin, Frederica von Stade, Twyla Tharp, and Beverly Sills–all of which I attended for free.

Richard Harriman, the man who co-founded and directed the series and after whom it would later be named, graduated from Jewell in 1953 and joined its English faculty in 1962. Three years later he decided that the college ought to be in the business of presenting great performances. He extracted three thousand dollars from the administration and proceeded to book Edward Villella, Patricia MacBride, and Jan Peerce. Not long after that, Liberty, Missouri, the suburb of Kansas City where William Jewell College is located, had become known throughout America as the place where world-famous musicians tried out the programs they would later perform in New York.

Richard Harriman, the man who co-founded and directed the series and after whom it would later be named, graduated from Jewell in 1953 and joined its English faculty in 1962. Three years later he decided that the college ought to be in the business of presenting great performances. He extracted three thousand dollars from the administration and proceeded to book Edward Villella, Patricia MacBride, and Jan Peerce. Not long after that, Liberty, Missouri, the suburb of Kansas City where William Jewell College is located, had become known throughout America as the place where world-famous musicians tried out the programs they would later perform in New York.

Mr. Harriman–I never got used to calling him Dick, not even after I grew up, moved to New York, and became a full-time critic of the arts–was the most genial of impresarios, a famously soft-spoken man who never had a bad word to say about anyone, at least not in my hearing. Nor did I ever hear anyone say a bad word about him. He was kind, sweet-natured, and impeccably tasteful in every aspect of his life and work. That he took an interest in me when I was an undergraduate was one of the luckiest breaks in a life that has been full of good fortune.

In addition to giving away free tickets to any student willing to line up and claim them, Mr. Harriman took a group of arts-conscious students to New York each winter and shepherded them to performances of every imaginable kind. I went on that trip in December of 1975, and wrote about it years later in a memoir of my youth:

Rummaging through my mother’s cupboard the other day, I found a manila envelope full of souvenirs of my visit to New York. There was my program from Harold Prince’s Broadway production of Candide; there were Lincoln Center and Radio City Music Hall and Mikhail Baryshnikov, fresh out of Rusia, soaring across the stage of the Uris Theater; there was a memorandum scrawled in an unformed hand on Waldorf-Astoria stationery (when you traveled with Mr. Harriman, you traveled first-class) telling where I had eaten dinner each night. The food I ate dazzled me as much as the sights I saw, for I had been raised on Kraft Dinner and Chef Boy-Ar-Dee pizza in a box, and the act of ordering vichyssoise from a haughty waiter at “21” very nearly made me swoon.

In later years I would occasionally run into Mr. Harriman in the lobby of a Manhattan theater or concert hall. We would swap snippets of performing-arts gossip, and I always tried to conduct myself not as a former student but as a colleague. It was, of course, an act, and a poor one. He had been present at the creation of my career, and it was impossible for me to talk to him without being intensely and inhibitingly aware of how very much I owed him.

It would have been no more possible for me to thank him to his face for what he had done for me, but I was able to do it from a safe distance when Achieve, William Jewell’s alumni magazine, asked me to write a few words of tribute when his series celebrated its fortieth anniversary and was renamed the Harriman Arts Program. This is what I wrote:

Cézanne called the Louvre “the book in which we learn to read.” The Harriman Arts Program was the book in which I learned to see, hear, and love the performing arts. It gave me a golden yardstick of taste–one I still use to this day.

Mr. Harriman died this afternoon at the age of seventy-seven. I bless and revere his memory.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

Your essay reminds me of something very important that is easy to forget: that a civilization’s art and culture are preserved and kept alive when related to as a highly personal and carefully selected gift from one generation to the next, from an individual to a valued friend. This is exactly what Harriman gave to his students and general audiences.

So it was. Well said.

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• La Cage aux Folles (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Fela! * (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Million Dollar Quartet (jukebox musical, G, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, closes Aug. 22, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, original Broadway production reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Our Town (drama, G, suitable for mature children, reviewed here)

IN ASHLAND, ORE.:

• Hamlet (Shakespeare, PG-13, closes Oct. 30, reviewed here)

• Ruined (drama, PG-13/R, violence and adult subject matter, closes Oct. 31, reviewed here)

• She Loves Me (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, closes Oct. 30, reviewed here)

IN GARRISON, N.Y.:

• The Taming of the Shrew/Troilus and Cressida (Shakespeare, PG-13, playing in rotating repertory through Sept. 5, reviewed here)

IN GLENCOE, ILL.:

• A Streetcar Named Desire (drama, PG-13, adult subject matter, extended through Aug. 15, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• The Grand Manner (drama, PG-13, adult subject matter, closes Aug. 1, reviewed here)

• The Merchant of Venice (Shakespeare, PG-13, adult subject matter, closes Aug. 1, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN CHICAGO:

• The Farnsworth Invention (drama, G, too complicated for children, closes July 24, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN OGUNQUIT, ME.:

• The Sound of Music (musical, G, completely child-friendly, closes July 24, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CHICAGO:

• Killer Joe (black comedy-drama, X, extreme violence and nudity, reviewed here)

TT: Almanac

“Now the world in general doesn’t know what to make of originality; it is startled out of its comfortable habits of thought, and its first reaction is one of anger.”

W. Somerset Maugham, Great Novelists and Their Novels