Mrs. T and I are flying back to New York tomorrow afternoon–or so we hope. We’ve been watching the news of the Great Christmas Blizzard of 2010 from a very safe distance, and I can’t begin to tell you how relieved we are not to have been on the move yesterday.

A week in Smalltown, U.S.A., has slowed my mental clock down to a comfortable crawl. I don’t have any more deadlines to hit until 2011, and I’m profoundly grateful for that as well. Instead of hammering away at the MacBook, I’ve been spending time with my mother, brother, sister-in-law, and spouse, opening presents and eating casseroles and doing dishes. Mom, Mrs. T, and I watch a movie every night (the week’s fare has included Mildred Pierce, The Bishop’s Wife, and The Great Escape) and sleep late every morning.

I could get used to this, except that, of course, I can’t. My real life beckons: I have a show to see on Saturday and a review to file the next morning. Snow or no snow, the merry-go-round awaits me, and I guess I won’t be sorry to get up on the horse again–but I suspect it won’t be long before I start to miss the deep white peace of our happy, uneventful week in Smalltown.

Archives for 2010

TT: Night thoughts on Jack Benny

I’ve been reading a book—not a new one, alas—about Jack Benny. The experience has proved to be unexpectedly sobering.

Benny died in 1974, the year that I graduated from high school, and is now, so far as I can tell, pretty much unknown to everyone younger than I am. Yet there was a time when he was one of the most famous people in America, and his fame was not short-lived: he appeared weekly on radio from 1932 to 1955 and regularly on TV from 1950 to 1965. Nor was he in any way culturally insignificant. Benny and his writers may not have invented situation comedy, but it’s generally agreed that they perfected it. (Gary Giddins has written perceptively about Benny’s contributions to modern comedy.) So why is he forgotten today?

The answer is, of course, that Benny did his best and most individual work on network radio, a medium that hit the skids around 1950 and for all intents and purposes ceased to exist in 1962, when the last surviving weekly dramatic series, Suspense and Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar, were cancelled by CBS. Virtually all of Benny’s radio shows were recorded, most of them in decent sound, and a high percentage of them can be heard on line by anyone who cares to search for them. Alas, few are inclined to bother, and so it seems highly unlikely that any classic radio series, even one as good as The Jack Benny Program, will find a new audience in the twenty-first century.

The answer is, of course, that Benny did his best and most individual work on network radio, a medium that hit the skids around 1950 and for all intents and purposes ceased to exist in 1962, when the last surviving weekly dramatic series, Suspense and Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar, were cancelled by CBS. Virtually all of Benny’s radio shows were recorded, most of them in decent sound, and a high percentage of them can be heard on line by anyone who cares to search for them. Alas, few are inclined to bother, and so it seems highly unlikely that any classic radio series, even one as good as The Jack Benny Program, will find a new audience in the twenty-first century.

That a giant of comedy like Jack Benny should have faded from our collective consciousness is not all that surprising, though it makes me sad, as do all such manifestations of the vanity of human wishes. What really jolted me was to read the other day that the Jimmy Stewart Museum was in dire financial straits. Stewart, needless to say, appeared in a considerable number of the most popular and critically acclaimed movies made in Hollywood in the twentieth century. But now that so many young people are unwilling to watch movies made before they were born, I find myself wondering whether any actor of the studio era, even the universally admired star of such celebrated films as Anatomy of a Murder, It’s a Wonderful Life, The Philadelphia Story, Rear Window, The Shop Around the Corner, and Vertigo, can count on being widely remembered over the very long haul.

As for Benny, I suspect that he will be remembered longest for his role in Ernst Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be, the only first-rate film in which he starred. You don’t have to know anything about Benny to appreciate the uncanny skill with which he impersonates a ham actor who longs desperately to play Hamlet, and that is why his performance in To Be or Not to Be can still be appreciated today.

Not so Benny the radio star, whose hopelessly inept violin playing and pretended stinginess and vanity long ago disappeared into the cultural memory hole. Up to a point, I’m sorry to see them go. For anyone at all familiar with Benny’s painstakingly worked-up comic persona, his show remains a fully valid theatrical experience, and were there world enough and time, I’d happily fritter away half-hour upon half-hour listening to one episode after another on my iPod.

Now that I’ve settled into middle age, though, I’m increasingly inclined to feel that life is too short to waste on situation comedies, even those as splendidly wrought as the radio version of The Jack Benny Program. (The TV version, though effective, wasn’t nearly as good.) I need richer, more emotionally complex comic fare, be it Noël Coward, Howard Hawks, or Shakespeare—or the brilliantly concise animated cartoons of the Forties and early Fifties, which can still make me laugh out loud. Not so the shows that occupy the airwaves today. I loathe the snarky, reflexively referential Irony Lite of today’s single-camera TV comedies and animated sitcoms.

At the same time, I now find even the best sitcoms of the Sixties and Seventies to be insufficiently pointed to satisfy my mature taste. As much as I love to laugh, I find that these series are no longer capable of supplying me with the aesthetic and spiritual nourishment that I need to get through the day. I want comedy that bites—hard—and the closer it gets to the knuckle, the louder I laugh. I wonder whether I’ll still feel that way when I grow old.

TT: Just because

Gerry Mulligan and Ben Webster play “Who’s Got Rhythm” in 1963:

TT: Almanac

“The basis of optimism is sheer terror.”

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

TT: To you and yours…

…much joy and much love—today, tomorrow, and always.

TT: Safety first, surprises second

Today’s Wall Street Journal drama column is my annual best-of-the-year wrapup: “It’s been a rocky year for American theater—and not just for the accident-prone members of the cast of Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. In the musical’s latest mishap, a stunt double was injured during a preview performance on Monday. No doubt his colleagues are starting to wonder whether they ought to look for a safer line of work. Money is tight, playgoers are staying home, donors are saying no and artistic directors are playing it safe, opting for small-cast shows and familiar comedies instead of hard-hitting drama. Yet there was still more than enough to see as I criss-crossed the land in search of great shows.”

Today’s Wall Street Journal drama column is my annual best-of-the-year wrapup: “It’s been a rocky year for American theater—and not just for the accident-prone members of the cast of Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. In the musical’s latest mishap, a stunt double was injured during a preview performance on Monday. No doubt his colleagues are starting to wonder whether they ought to look for a safer line of work. Money is tight, playgoers are staying home, donors are saying no and artistic directors are playing it safe, opting for small-cast shows and familiar comedies instead of hard-hitting drama. Yet there was still more than enough to see as I criss-crossed the land in search of great shows.”

Among other things, I single out Gordon Edelstein’s breathtakingly fresh and poignant production of Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie (pictured here) as the best revival of the year and Chicago’s TimeLine Theatre as the company of the year:

Chicago’s TimeLine Theatre, which specializes in “stories inspired by history,” outdid itself with better-than-the-original productions of Aaron Sorkin’s “The Farnsworth Invention” and Peter Morgan’s “Frost/Nixon” performed in its own 87-seat theater, showing that a small troupe with creativity and nerve to burn can make as much magic as a big-ticket Broadway extravaganza….

To find out what what else I liked in 2010, go here.

TT: The beautiful sound of sorrow

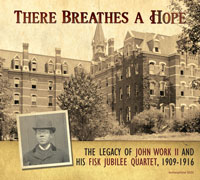

In today’s “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal, I write about Archeophone Records’ There Breathes a Hope: The Legacy of John Work II and His Fisk Jubilee Quartet, 1909-1916. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Century-old records are the closest thing we have to a time machine. To listen to the voice of Theodore Roosevelt or the piano playing of Claude Debussy is to feel the years falling away like autumn leaves from a maple tree. Rarely, though, have I been so engrossed by an album remastered from antique 78s as I was by “There Breathes a Hope: The Legacy of John Work II and His Fisk Jubilee Quartet, 1909-1916,” an anthology released by Archeophone Records. This two-CD set, which also includes a profusely illustrated 100-page booklet, contains 43 of the first recordings of black spirituals. It is the most important historical reissue of 2010–and one that tells a story about turn-of-the-century black culture that may make some listeners squirm with retrospective discomfort.

Nashville’s Fisk University, which opened its doors in 1866, is one of America’s oldest historically black colleges. It is also known to scholars of American music as the home of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an ensemble founded in 1871 that introduced concertgoers around the world to such deathless songs of sorrow and hope as “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and “Roll Jordan Roll,” in the process raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for the inadequately funded school. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers disbanded before the invention of the phonograph, but in 1899 John Work II, a teacher at Fisk, reorganized the group, and a male quartet drawn from the chorus started making recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1909.

Nashville’s Fisk University, which opened its doors in 1866, is one of America’s oldest historically black colleges. It is also known to scholars of American music as the home of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an ensemble founded in 1871 that introduced concertgoers around the world to such deathless songs of sorrow and hope as “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and “Roll Jordan Roll,” in the process raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for the inadequately funded school. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers disbanded before the invention of the phonograph, but in 1899 John Work II, a teacher at Fisk, reorganized the group, and a male quartet drawn from the chorus started making recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1909.

No matter how much you think you know about spirituals, I think you’ll be surprised to hear these performances, because few of them sound anything like what you’re likely to be expecting. Their musical tone is formal, sometimes even a bit staid, as if you were hearing four gentlemen in high-button shoes warbling close-harmony hymns in the parlor. Not always–the quartet tosses off the syncopations in the up-tempo tunes with a light, dancing touch–but it’s downright startling to hear them sing “CHAH-ree-AHT” in the very first recording of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” No less surprising is that they recorded “Old Black Joe,” one of Stephen Foster’s nostalgic plantation songs, at their third session….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: ‘Tis the season (IV)

Louis Armstrong recites “The Night Before Christmas”: