I received the first copy of the paperback edition of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong in yesterday’s mail. It’ll be published by Mariner Books on October 7, and you can already order a copy from Amazon by going here.

I received the first copy of the paperback edition of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong in yesterday’s mail. It’ll be published by Mariner Books on October 7, and you can already order a copy from Amazon by going here.

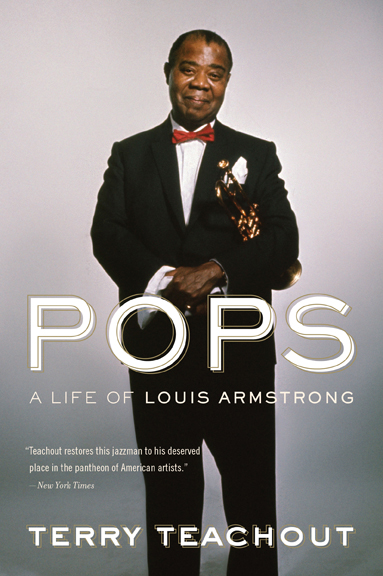

The Pops paperback is a good-looking piece of work, bestrewn inside and out with vanity-piquing quotes from some of the book’s admiring reviewers. Even if you already own the hardcover edition, you might want to consider buying a copy of the paperback for two reasons. Not only did I correct a dozen or so niggling little errors in the text, but Mariner has also fixed the cover photograph of Armstrong, which was inadvertently reversed on the original dust jacket.

The funny thing about this blunder is that nobody who knew Armstrong–including four close friends of his who read the manuscript of Pops–noticed it. It wasn’t until I received a pair of e-mails from James Breig and Kenny Harris, two readers of this blog who have very sharp eyes, that I realized that the cover photo had been flipped. Now that I’m able to view the two editions side by side, I’ll confess that I can still barely tell the two Satchmos apart. Except for a tiny depression on his forehead, he was a symmetrical-looking guy.

Be that as it may, I’m delighted to nudge Pops a bit closer to perfection. I sat down last night and read through it for the first time in months, and I was pleased and proud. I think I did right by Louis Armstrong. I hope you agree.

Archives for 2010

TT: Almanac

“Civilizations have been founded and maintained on theories which refused to obey facts.”

Joe Orton, What the Butler Saw

TT: Almanac

“What good is an obscenity trial except to popularize literature?”

Rex Stout, The League of Frightened Men

TT: Loving tongue

I just received in the mail two copies of Pops: A Vida de Louis Armstrong, the Brazilian edition of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, which was published last month by Larousse. The design of the book is essentially identical to that of the American edition, except that it’s in Portuguese. The translators are Andrea Gottlieb and Castro Neves, and I wish I could tell you that they did a fabulous job. Alas, I must confess to being humiliatingly ignorant of a language to which I have nonetheless spent countless hours listening. Would that my longstanding passion for the music of Antônio Carlos Jobim, João Gilberto, Sérgio Mendes, Luciana Souza, and Trio da Paz had miraculously caused me to learn Portuguese by osmosis, but the only word I know in that lovely, liquid tongue is, appropriately enough, saudade.

I just received in the mail two copies of Pops: A Vida de Louis Armstrong, the Brazilian edition of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, which was published last month by Larousse. The design of the book is essentially identical to that of the American edition, except that it’s in Portuguese. The translators are Andrea Gottlieb and Castro Neves, and I wish I could tell you that they did a fabulous job. Alas, I must confess to being humiliatingly ignorant of a language to which I have nonetheless spent countless hours listening. Would that my longstanding passion for the music of Antônio Carlos Jobim, João Gilberto, Sérgio Mendes, Luciana Souza, and Trio da Paz had miraculously caused me to learn Portuguese by osmosis, but the only word I know in that lovely, liquid tongue is, appropriately enough, saudade.

Even though I’ll have to leave it to my Brazilian friends to tell me whether Ms. Gottlieb and Mr. Neves got it right, I still managed to spend an exceedingly pleasant hour leafing through the Brazilian edition of Pops and marveling at how much cooler I seem to sound in Portuguese. My favorite passage from Pops, for instance, is the last paragraph:

Faced with the terrible realities of the time and place into which he had been born, he did not repine, but returned love for hatred and sought salvation in work. Therein lay the ultimate meaning of his epic journey from squalor to immortality: his sunlit, hopeful art, brought into being by the labor of a lifetime, spoke to all men in all conditions, and helped make them whole.

Here it is in Portuguese:

Confrontado pelas terríveis realidades do lugar e da época em que nasceu, ela não se afligiu, mas retribuiu ódio com amor e procurou a salvação no trabalho. É aí que está o resultado supremo da épica jornada que percorreu da esqualidez à imortalidade: sua arte, iluminada pelo sol, cheia de esperança, criada pelo trabalho de uma vida e capaz de tocar todos os homens de qualquer condição, e torná-los completos.

Doesn’t that just make you want to roll over and purr?

As I flipped through the book, I ran across a number of additional footnotes that were credited to the translators. Notwithstanding my inability to speak Portuguese, I could see that their purpose was to explain to Brazilian readers the meanings of various untranslatable English-language expressions, including Uncle Tom, minstrel show, black-and-tan club, poboy, hepcat, and–this one is my favorite–The Jetsons:

As I flipped through the book, I ran across a number of additional footnotes that were credited to the translators. Notwithstanding my inability to speak Portuguese, I could see that their purpose was to explain to Brazilian readers the meanings of various untranslatable English-language expressions, including Uncle Tom, minstrel show, black-and-tan club, poboy, hepcat, and–this one is my favorite–The Jetsons:

Familio do desenho animado de mesmo nome da Hanna-Barbera, criado nos anos 1960 e ambientado no ano de 2062, no qual o futuro é descrito como um mundo de robôs, hologramas, carros voadores etc.

I suspect that these footnotes are in large part responsible for the other main difference between the two versions of Pops, which is that the Brazilian edition is thirty-six pages longer than the American edition.

I was fascinated, by the way, to read the following translation and explication of these lines from a song by Fats Waller and Andy Razaf: My only sin is in my skin/What did I do to be so black and blue? Take it away, colleagues:

Meu único pecado está na minha pele/O que fiz para ser tão negro e trist? [blue, em inglês, significa tanto a cor azul quanto tristeza].

Quanto tristeza, indeed!

* * *

Luciana Souza sings “Docemente” with the Fred Hersch Trio:

If an audiobook version of Pops should ever be published in Brazil, I’d like her to read it.

TT: Almanac

“Well, here I went to Long Island Rail Road. It’s the first time I’ve done that, so I got to Penn Station really early, so I could ask directions. Some of the policemen recognized me, and I bought my senior ticket to Montauk for $11, off peak. I sat in the waiting room with a lot of people, and occasionally somebody recognized me. It’s lovely, and it’s very important to be respectful of it and accept it. Occasionally I have to be aware that there is also, in some people, a degree of resentment, as though I would think that I’m any different than anyone else. I’m not. I thrive on modesty and humility. I never said that I had perspective and judgment.”

Elliott Gould, interview, New York Times, Sept. 3, 2010

TT: Just because (in memoriam)

Pablo Casals plays the G Major Cello Suite at the Prades Festival in 1954:

TT: Almanac (in memoriam)

“I would define true courage to be a perfect sensibility of the measure of danger, and a mental willingness to endure it.”

William Tecumseh Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman

CAAF: War and Peace and fathers

I’m reading War and Peace right now, and it’s exhilarating. I’ve always meant to and I had an idea that I’d read it this fall in preparation for Freedom so that I’d get the War and Peace allusions that Kakutani says are there (although she calls them “laughably conceited“). Which means, if you’re currently reading Freedom, I look forward to discussing it with you in spring 2012.

I finished Part 1 this morning (a little over 100 pages in) and was pretty sodden with a pile of used Kleenex beside me. That section ends with Prince Andrei’s departure for the war, with his father screaming him out the door of his study in an excess of nerves and then blowing his nose over and over once the door is shut. So far I’m finding the novel’s male characters especially affecting, and this scene, with the father’s agitation, did me in. (One of my nephews served several years in Iraq, and when he came home, there was a big breakfast here in Asheville at which my dad, in his relief and pride but already in poor health, kept sending pancakes from his plate down the table to my nephew, who had a full plate of his own. Person to person, fork to fork, the pancakes would go. Prince Andrei and his father are, of course, on the other side of this emotional equation, with the young man just heading off, neither knowing what is to come.)

The other leave-taking between a father and son happens when Pierre, an illegitimate son, is called to the deathbed of his father, the count, and in his awkwardness doesn’t know what to do. He stands by as people minister to his father, and there’s this tremendous moment where his father, being lifted by attendants, passes his son held high in the air, which shocked me both because the entire scene is so moving and because it’s echoed (consciously, I think) in Nabokov’s famous image of his father levitating in the sky in Speak, Memory.

From War and Peace (I’m reading the Pevear-Volokhonsky translation):

The carriers, who also included Anna Mikhailovna, came even with the young man, and for a moment, over people’s backs and necks, he saw the high, fleshy, bared chest and massive shoulders of the sick man, raised up by the people who held him under the arms, and his curly, gray leonine head.

And Nabokov’s memorial description of his father being tossed in the air by the estate’s peasants (“a token of gratitude”), which closes chapter one:

From my place at the table I would suddenly see through one of the west windows a marvelous case of levitation. There, for an instant, the figure of my father in his wind-rippled white summer suit would be displayed, gloriously sprawling in midair, his limbs in a curiously casual attitude, his handsome, imperturbable features turned to the sky. Thrice, to the mighty heave-ho of his invisible tossers, he would fly up in this fashion, and the second time he would go higher than the first and then there he would be, on his last and loftiest flight, reclining, as if for good, against the cobalt blue of the summer noon, like one of those paradisiac personages who comfortably soar, with such a wealth of folds in their garments, on the vaulted ceiling of a church while below, one by one, the wax tapers in mortal hands light up to make a swarm of minute flames in the mist of incense, and the priest chants of eternal repose, and the funeral lilies conceal the face of whoever lies there, among the swimming lights, in the open coffin.