I review the Broadway premiere of David Mamet’s A Life in the Theatre in the Greater New York section of today’s Wall Street Journal, and the verdict is mostly very positive. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

David Mamet is the most American of playwrights. Not only do his snarlingly competitive characters take a zero-sum view of human relationships, but they express it with words that fly through the air like bullets in search of a body. So what could have possessed Patrick Stewart–make that Sir Patrick Stewart–to wrestle with “A Life in the Theatre,” Mr. Mamet’s 1977 play about a pair of actors, one old and one young, who are battling for dominance over one another? Beats me, but I’m glad it did, for Mr. Stewart’s performance, strange though it may sound from time to time, is in the end both deeply comprehending and painfully touching, just like the play itself.

I can’t think why it took so long for “A Life in the Theatre” to get to Broadway. It’s a natural, a two-character comedy with a wrenchingly serious coda and a plum part for a first-class actor who is capable of convincingly portraying a tired old ham. As usual, Mr. Mamet tells us nothing about his characters beyond the words that they speak, but we are, I think, invited to suppose that Robert (Mr. Stewart) and John (T.R. Knight) are working together in the kind of second-rate repertory company that shoves a new production onto the boards every week or two, ready or not. In many of the 26 scenes, we see Robert and John doing their best to stagger through a series of underrehearsed scripts (one of which is a cruelly clever Eugene O’Neill parody). Elsewhere we look on as Robert tries to make John his protégé, hosing him down with gaseous lectures about the craft of theater…

Mr. Stewart plays Robert very much in the English manner, and at first I feared that his pacing would be unidiomatically deliberate (I smiled to hear him wring five finicky syllables out of the word “specifically”). Then I let go of my preconceptions and started watching the performance he was giving instead of the one I wanted to see, and before long I’d stopped keeping score and was enthralled….

* * *

The print version of the Journal‘s Greater New York section only appears in copies of the paper published in the New York area, but the complete contents of the section are available on line, and you can read my review of A Life in the Theatre by going here.

Archives for 2010

TT: Snapshot

Carl Sandburg appears as the mystery guest on a 1960 episode of What’s My Line?:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Like everybody who is not in love, he imagined that one chose the person whom one loved after endless deliberations and on the strength of various qualities and advantages.”

Marcel Proust, Sodome et Gomorrhe (Cities of the Plain)

TT: Entry from an unkept diary

• As I’ve written elsewhere, I no longer find Neil Simon’s plays to be very funny. His insert-flap-A-in-slot-B style of joke-driven comedy strikes me as a rusty relic of the increasingly distant past. But there are those who insist that there’s more to Simon than his punchlines, and so I took a look at the 1975 film version of The Sunshine Boys the other day in an attempt to see for myself what his critical advocates see in him. I tried to watch The Sunshine Boys a couple of years ago and couldn’t get anywhere with it–but this time I saw the film from a different point of view.

What hit me forcibly on a second viewing was that Willie Clark, the character played in the film by Walter Matthau, is not merely an absent-minded old grouch but is all too clearly suffering from dementia. Yes, Simon plays his confusion for laughs–he plays everything for laughs–but anyone who has spent time with a friend or relative afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease will immediately spot the symptoms, which are portrayed with next to no comic exaggeration:

What hit me forcibly on a second viewing was that Willie Clark, the character played in the film by Walter Matthau, is not merely an absent-minded old grouch but is all too clearly suffering from dementia. Yes, Simon plays his confusion for laughs–he plays everything for laughs–but anyone who has spent time with a friend or relative afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease will immediately spot the symptoms, which are portrayed with next to no comic exaggeration:

BEN It’s Monday, not Wednesday…didn’t you know it was Monday?

WILLIE I remembered but I forgot.

In 1972, when The Sunshine Boys opened on Broadway, the phrase “Alzheimer’s disease” had yet to become part of the national lexicon. I recently shared a platform with Marion Roach, who mentioned in passing that a piece about her mother’s battle with Alzheimer’s that she wrote for the New York Times Magazine in 1983 was, unlikely as it may sound, the first first-person account of the disease ever to be published. A quarter-century later, we all know what Alzheimer’s disease is, and damned few of us are inclined to laugh at it.

I still don’t think The Sunshine Boys is all that funny, but when you view it not as a comedy but as a drama, the punchlines recede in salience and you find yourself confronted with a portrait of an angry, frightened old man that is fraught with something not far removed from pathos. So given the fact that Neil Simon’s plays haven’t been doing especially well in revival of late, I find myself wondering: what would The Sunshine Boys be like if it were staged not for laughs but truth, the way that Matthew Warchus staged last year’s Broadway revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s The Norman Conquests?

As I wrote in my Wall Street Journal review of that remarkable production:

Matthew Warchus is well aware of the bleak undertones of “The Norman Conquests.” He went so far in a recent interview as to claim that he’d directed the triptych “as if it’s Chekhov.” I wouldn’t go quite as far as that: Mr. Warchus is a master of physical comedy, and each installment is full of the same knockabout antics that can be seen in his production of “God of Carnage,” which is currently playing to packed houses on Broadway. But he also understands the delicate art of silence, and “The Norman Conquests” is no less full of moments of stillness when the laughter dies away and all you can hear is the keening sound of sorrow.

Perhaps Simon’s play isn’t strong enough to stand up to that kind of tough-minded treatment. David Cromer, after all, staged Brighton Beach Memoirs that way, and it closed after just nine performances. But what if some similarly inclined director were to mount The Sunshine Boys not on Broadway but in a small, first-class regional house like, say, Palm Beach Dramaworks or Chicago’s Writers’ Theatre, where the audience, instead of insisting on being “entertained,” would presumably be more willing to go where the production led them?

“If [Simon’s] plays continue to be performed,” I wrote in my Wall Street Journal review of Brighton Beach Memoirs, “it will only be because actors and directors have found a new way of performing them, one that cuts through the punch lines to find a deeper, more enduring dramatic truth.” Might The Sunshine Boys be the place to start?

* * *

A studio featurette about the making of the film version of The Sunshine Boys:

TT: Almanac

“We are healed of a suffering only by experiencing it to the full.”

Marcel Proust, Albertine disparue (The Sweet Cheat Gone)

TT: Not unlike

The past, we’re told, was in color, and I don’t doubt that the generation after mine will remember it that way. Mrs. T told me the other day that Ian, our thirteen-year-old nephew, has taken to turning up his nose at black-and-white movies, a form of youthful snobbery that I’d heard about but never previously encountered. Not for him the clean, crisp surreality of the monochrome image: he wants color or nothing. No doubt blood looks better when it’s really red.

Me, I like black-and-white movies, and I can recall with embarrassing ease a time when color TV was a rarity reserved for the rich. The earliest color TV sets, which went on sale in 1954, cost $1,295 each, a bit more than ten thousand dollars in today’s money. My family, which didn’t have that kind of cash to throw around, waited to buy a color set until 1966, the year that all three networks (remember the three networks?) changed over to full-color prime-time broadcast schedules. Prior to that time, the world came to our living room in black and white, and even though commercial color TV had been introduced twelve years earlier, I knew it not. That’s why it’s natural for me to think of the not-so-distant past as a colorless realm inhabited by great men (and a few women) who now exist only in shades of gray.

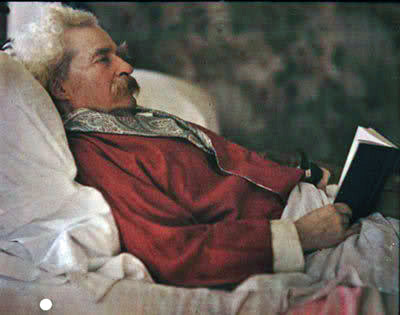

It is for this reason that I find myself fascinated by the relatively recent explosion of interest in autochrome, the first color-photography process that was practical enough to be marketed commercially and used by serious photographers. It was in autochrome that the earliest color pictures of famous people were taken, and to see them now is a disorienting, even jolting experience. Alvin Langdon Coburn, for instance, took two autochromes of Mark Twain at his home in Connecticut. Who knew that the author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn liked to wear a red robe when reading in bed? Who knew, indeed, that there was any color to him but the gleaming white of the linen suits that were his trademark?

It is for this reason that I find myself fascinated by the relatively recent explosion of interest in autochrome, the first color-photography process that was practical enough to be marketed commercially and used by serious photographers. It was in autochrome that the earliest color pictures of famous people were taken, and to see them now is a disorienting, even jolting experience. Alvin Langdon Coburn, for instance, took two autochromes of Mark Twain at his home in Connecticut. Who knew that the author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn liked to wear a red robe when reading in bed? Who knew, indeed, that there was any color to him but the gleaming white of the linen suits that were his trademark?

Dwight Eisenhower is another of those historical figures who, though he was photographed countless times in color, seems to be locked into the lost world of shadows. Hence I was hugely surprised to discover that the oldest known color videotape, made in 1958, records a public appearance by none other than Ike himself:

It was far less surprising for me to view the color tape of the 1959 “kitchen debate” between Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev. Nixon, after all, was elected president when I was in junior high school. What startled me most about the tape was not that he was (so to speak) a man of color but that, like me, he had once been young:

Most fascinating of all, though, is the fact that the earliest surviving color videotapes of entertainment telecasts should be devoted to the three TV specials featuring Fred Astaire that aired on NBC between 1958 and 1960. Astaire, needless to say, starred in a good many color films, but the movies for which he is best remembered are all in black and white, and to see his dancing preserved via the you-are-there immediacy of videotape is to feel the obscuring veil of the past falling away like a layer of shed skin.

Some clever soul has posted on YouTube an excerpt from Another Evening With Fred Astaire in which the original color video is intercut with a black-and-white film kinescope of the same telecast. If you’re too young to know what it felt like to see color TV for the first time, this clip will convey something of that long-lost shock of recognition:

I confess to treasuring the non-entertaining portions of these telecasts as much as, if not more than, the “good” parts. Here, for instance, is part of what you would have seen if you were one of the few people in Wichita, Kansas, who was sufficiently well heeled to own a color TV on October 17, 1958:

Isn’t it bewitching to see the car commercials? And to know that Lee Marvin’s M Squad and Peter Lawford’s The Thin Man got bumped that cool fall night by none other than Fred Astaire?

Alas, there will be no future autochrome-like explosion of interest in early color television, for videotape was so expensive in the late Fifties and early Sixties (an hour-long blank reel cost $300) that all three networks routinely erased and reused tapes that had not been specifically earmarked for preservation. Surviving color video from the Golden Age of Television is thus as rare–and as eerily evocative–as sound recordings from the late nineteenth century.

The world was simpler then, simpler and more reassuring and–yes–less honest. Much was being swept under the rug in 1960, much suffering and much folly, far too much for our collective good. And now? We get color or nothing, with more than enough blood to go around. But while I suppose I’m glad to know what I know about the world, luridly and garishly vivid though it may be, I don’t think I would have wanted to know very much of it when I was young–and I’m not at all sure it’s a good thing that my nephew already knows some of it.

W.H. Auden said it: Some think they’re strong, some think they’re smart,/Like butterflies they’re pulled apart,/America can break your heart./You don’t know all, sir, you don’t know all.

* * *

To see the complete 1958 telecast of An Evening With Fred Astaire, go here.

TT: Almanac

“By art alone we are able to get outside ourselves, to know what another sees of this universe which for him is not ours, the landscapes of which would remain as unknown to us as those of the moon.”

Marcel Proust, The Past Recaptured

TT: Suspicious minds

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report on my recent visit to Cleveland’s Great Lakes Theater Festival, where I saw new productions of Othello and An Ideal Husband. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

When a drama company puts on two shows in alternating repertory, it’s smart for the artistic director to pick a pair of scripts that can be played off one another–though not necessarily in an obvious way. You wouldn’t think, for instance, that Shakespeare’s “Othello” and Oscar Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband” have much of anything in common, but they prove in practice to be mutually illuminating, bearing as they do on the subject of how suspicion can wreak havoc on a marriage. Cleveland’s Great Lakes Theater Festival is mounting handsome stagings of both plays in collaboration with the Idaho Shakespeare Festival, where the two productions originated this summer, and as I watched them in close succession earlier this week, I was struck by how smoothly they fit together.

Risa Brainin’s “Othello” is a modern-dress staging whose reference points are wholly contemporary, all the way from the clamorous action-flick incidental music of Michael Keck to the central-casting performances of the excellent actors: Othello (David Alan Anderson) plays the regular guy gone wrong, Iago (David Anthony Smith) the brash, sarcastic Bill Murray-ish sidekick with a giant chip on his shoulder, Desdemona (Sara M. Bruner) the chirpy innocent who can’t believe what’s happening to her until it’s too late. The results, though unsubtle in the extreme, are also terrifically effective–and not just on their own populist terms, either. This is a blood-and-thunder “Othello” that roars down the track at several hundred miles an hour…

Nearly every production of an Oscar Wilde play that I’ve seen in recent years has been performed on a set that sought to reproduce more or less literally the Vicwardian décor of Wilde’s own time. Not so the Great Lakes Theater Festival’s version of “An Ideal Husband,” whose simple unit set, designed by Nayna Ramey, consists of a drape, some columns and a half-dozen stage-wide steps, plus enough period chairs to allow the characters to seat themselves as they please. Between the set and Jason Lee Resler’s high-society costumes, nothing more is needed to create a look that is at once stylized and stylish.

Nearly every production of an Oscar Wilde play that I’ve seen in recent years has been performed on a set that sought to reproduce more or less literally the Vicwardian décor of Wilde’s own time. Not so the Great Lakes Theater Festival’s version of “An Ideal Husband,” whose simple unit set, designed by Nayna Ramey, consists of a drape, some columns and a half-dozen stage-wide steps, plus enough period chairs to allow the characters to seat themselves as they please. Between the set and Jason Lee Resler’s high-society costumes, nothing more is needed to create a look that is at once stylized and stylish.

Sari Ketter, the director, writes in her program note that she conceives of “An Ideal Husband” as a “fairy tale.” To that end she fills her sparsely decorated stage with a ballet-like corps of black-clad butlers at whose seemingly magical behest the other actors come and go, a charming conceit executed with the most delicate of touches….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.