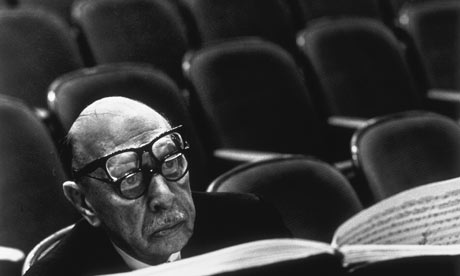

If you follow this blog regularly, you know that Paul Moravec and I are working on our second opera, Danse Russe, which has been commissioned by Philadelphia’s Center City Opera Theater and will be premiered in April. It’s a backstage comedy–we call it a vaudeville–about the making of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. The four characters, accordingly, are Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Pierre Monteux (who conducted the first performance of The Rite of Spring in Paris in 1913).

If you follow this blog regularly, you know that Paul Moravec and I are working on our second opera, Danse Russe, which has been commissioned by Philadelphia’s Center City Opera Theater and will be premiered in April. It’s a backstage comedy–we call it a vaudeville–about the making of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. The four characters, accordingly, are Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Pierre Monteux (who conducted the first performance of The Rite of Spring in Paris in 1913).

I haven’t had anything to say about Danse Russe in this space since the initial announcement of the commission because I’ve been too busy writing the opera to write about it, but I’m delighted (and relieved) to report that the libretto is now finished and Paul has drafted all but one scene of the piano score. That’s more than enough for Center City Opera to mount a workshop performance in Philadelphia next week.

On Friday, November 5, Paul and I will take part in a discussion of Danse Russe at Philadelphia’s Knapp Gallery. The workshop performance will take place the next afternoon. Both events are open to the public. To find out more and purchase tickets, go here.

Last week I was interviewed about Danse Russe at my New York apartment by Center City’s Mary Knapp. Excerpts from that interview have just been posted on YouTube, and you can view them here. Mary edited her questions out of the video, but they were good ones. If I do say so myself, I think my answers will tell you quite a bit about what Paul and I think we’re up to:

Archives for 2010

TT: Almanac

“People can foresee the future only when it coincides with their own wishes, and the most grossly obvious facts can be ignored when they are unwelcome.”

George Orwell, “London Letter,” Partisan Review, Winter 1945

DE-ROMANTICIZING THE BLUES

“By now, the sounds and rhythms of the blues are so ubiquitous that they seem almost to be embedded in the musical DNA of the human race–in part because their origins have long been shrouded in what can only be described as romantic myth. Even when scholars with musical training write about the emergence of the blues, the results can be starry-eyed and frankly sentimental…”

TT: How’s that noose fit, Mr. Bones?

In the Greater New York section of this morning’s Wall Street Journal, I review the Broadway transfer of The Scottsboro Boys, the new John Kander-Fred Ebb musical whose off-Broadway incarnation was one of last season’s most highly praised shows. I loathed most of it. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

I suspect that most of the younger people who come to see “The Scottsboro Boys” won’t know much about the Depression-era case that inspired the show, infamous though it once was. Very briefly, then, nine black boys from Georgia and Tennessee (one was 12, the others in their teens) who were riding the rails in search of work in 1931 were pulled off their train in Alabama, arrested by a local posse and accused of raping a pair of white girls who had been riding the same train. A few days later, having barely escaped lynching, they were convicted and sentenced to death. Their case became a nationwide cause célèbre, and the Supreme Court ruled that they had been denied due process and would have to be retried. But even though one of the women subsequently recanted her original testimony, five of the now-grown boys remained behind bars for years to come, the last one being paroled in 1950.

I suspect that most of the younger people who come to see “The Scottsboro Boys” won’t know much about the Depression-era case that inspired the show, infamous though it once was. Very briefly, then, nine black boys from Georgia and Tennessee (one was 12, the others in their teens) who were riding the rails in search of work in 1931 were pulled off their train in Alabama, arrested by a local posse and accused of raping a pair of white girls who had been riding the same train. A few days later, having barely escaped lynching, they were convicted and sentenced to death. Their case became a nationwide cause célèbre, and the Supreme Court ruled that they had been denied due process and would have to be retried. But even though one of the women subsequently recanted her original testimony, five of the now-grown boys remained behind bars for years to come, the last one being paroled in 1950.

In “The Scottsboro Boys,” Messrs. Kander and Ebb and David Thompson, the show’s librettist, have compressed this complicated sequence of events into a lengthy one-act musical that makes use of all the theatrical conventions of the old-fashioned blackface minstrel shows that were popular well into the 20th century. (Mr. Kander, who is 83, actually directed blackface shows at a Wisconsin boys’ camp in the Thirties.) Except for Mr. Cullum, who plays the master of ceremonies, the performers are all black, and most of the songs, which are written with a grasp of period style that will surprise no one familiar with such earlier Kander-Ebb shows as “Cabaret” and “Chicago,” are staged as grotesque parodies of the eye-rolling shuffle-and-grin style familiar to anyone who has seen films of Stepin Fetchit and Mantan Moreland…

“The Scottsboro Boys” would have been courageous had it been mounted on Broadway, or anywhere else in America, in the Sixties. In that long-gone decade, the prospect of watching a stageful of black men perform a “comic” minstrel show about so hideous an event would have stung like a flogging. But the intervening half-century has seen not only the election of a black president but the mounting of musicals like “Ragtime” and “Assassins” in which broadly similar theatrical techniques are used to identical ends, thereby robbing the caricatures in “The Scottsboro Boys” of their shock effect. I suppose there are places in America where such a show might still jolt its viewers, but to see “The Scottsboro Boys” on Broadway is to witness a nightly act of collective self-congratulation in which the right-thinking members of the audience preen themselves complacently at the thought of their own enlightenment….

* * *

The print version of the Journal‘s Greater New York section only appears in copies of the paper published in the New York area, but the complete contents of the section are available on line, and you can read my review of The Scottsboro Boys by going here.

TT: A reminder about tonight

In case you didn’t happen to see the blog on Friday, Candace Bushnell and I will be chatting about the novels of Elaine Dundy tonight at seven p.m. at the Barnes & Noble on East Eighty-Sixth Street in Manhattan. For more information about our joint appearance, which is open to the public, go here.

TT: Almanac

“Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand.”

George Orwell, Why I Write

ORIGINAL CAST ALBUM

Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson (Ghostlight). Now on CD, the score of the first Broadway musical ever to make fully effective and idiomatic use of rock. Michael Friedman’s hard-edged, guitar-driven emo-style songs are tuneful, smart, and catchy (especially “Ten Little Indians”). Nor is there the slightest trace of slickness: this is real rock, not the synthetic kind. See the show by all means, but the best of it is right here (TT).

BOOK

David Thomson, The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Updated and Expanded (Knopf, $40). There’s still no room for Whit Stillman or Parker Posey in the newly revised fifth edition of the most idiosyncratically interesting of all books about movies, which says much about the author’s increasingly quaint big-is-best perspective: David Thomson continues to believe that Hollywood has the power to make America a better place, and fears that it is no longer fulfilling its culture-shaping potential. Fortunately, you can easily ignore that aspect of the book and concentrate instead on its crisp, wholly personal, and unfailingly illuminating appraisals of everyone from Humphrey Bogart to Orson Welles. Thomson may be old-fashioned, but that doesn’t make him predictable, much less irrelevant (TT).