Erle Stanley Gardner, the creator of Perry Mason, appears as the mystery guest on a 1957 episode of What’s My Line?:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

Archives for August 2010

TT: Almanac

“Such is the irresistible nature of truth, that all it asks, and all it wants, is the liberty of appearing. The sun needs no inscription to distinguish him from darkness.”

Thomas Paine, The Rights of Man

TT: The return of Pops

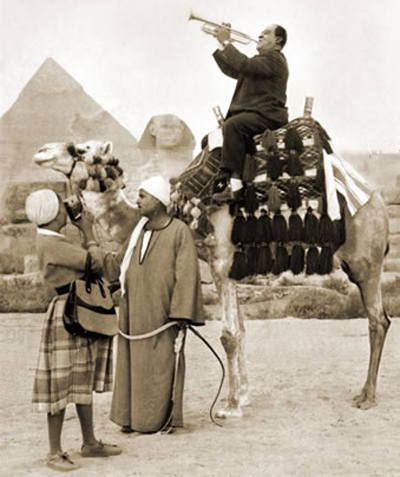

As I mentioned the other day, Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, like Dolly Levi, is still going strong. Not only will the corrected paperback edition be published by Mariner Books on October 7–which happens to be the third anniversary of my marriage to Mrs. T–but I continue to make Pops-related public appearances around the country. The latest of these is an outdoor reading and signing at New York’s Bryant Park that takes place on Wednesday, for which I’ll be joined by Jon-Erik Kellso, a tradition-minded trumpeter who knows his Pops backwards and forwards.

As I mentioned the other day, Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, like Dolly Levi, is still going strong. Not only will the corrected paperback edition be published by Mariner Books on October 7–which happens to be the third anniversary of my marriage to Mrs. T–but I continue to make Pops-related public appearances around the country. The latest of these is an outdoor reading and signing at New York’s Bryant Park that takes place on Wednesday, for which I’ll be joined by Jon-Erik Kellso, a tradition-minded trumpeter who knows his Pops backwards and forwards.

The festivities start at 12:30. For more information, go here and scroll down.

* * *

Jon-Erik Kellso and the Ear Regulars play “Please” at New York’s Ear Inn in 2009:

TT: Almanac

“It is a fool’s prerogative to utter truths that no one else will speak.”

Neil Gaiman, Dream Country

SHAME ON ELIE WIESEL

“Do you have a right not to be written about? Elie Wiesel thinks he does–and he’s prepared to sic his lawyers on anyone who thinks otherwise…”

TT: Once again, just because

Courtesy of Philip Terzian, the Count Basie Septet plays “One O’Clock Jump” in 1950. The band also includes Buddy DeFranco on clarinet, Clark Terry on trumpet, Wardell Gray on tenor sax, Jimmy Lewis on bass, Gus Johnson on drums, and–of course–Freddie Green on guitar:

TT: Entry from an unkept diary

• In recent weeks I’ve been dipping into Somerset Maugham, a writer whom I admire very much–with qualifications. One of the problems I have with Maugham relates to his most characteristic theme, which is obsessive “love” (by which he means sexual attraction). In Maugham’s novels and stories, it is common for seemingly unworthy people to be “loved” by men or women of a different social class. Nor do these presumed unworthies improve with closer inspection: the better you get to know them, as in the case of Mildred in Of Human Bondage or Albert, the chauffeur-lover of “The Human Element,” the less attractive they become. Maugham’s Mildreds and Alberts are usually portrayed as disagreeable, opportunistic, and–to put it gently–not very interesting. We are clearly expected to conclude that the sexual magnetism emitted by these unappetizing creatures is as irresistible as it is inexplicable, but it is never made manifest other than by authorial assertion.

Maugham was, of course, writing of his own experience, for the great love of his life, Gerald Haxton, was a singularly bad piece of work, drunken, disloyal, and unscrupulous in every conceivable way. Alas, Maugham was hopelessly obsessed with Haxton, and thus brought himself much grief.

My problem with Maugham’s writing arises from the fact that this kind of obsession is not an experience I recognize, which makes it impossible for me to sympathize other than theoretically with those of his characters who are so enthralled. Try as I might, I can’t put myself in the place of a person like Philip Carey, the hero of Of Human Bondage, who seems to adore Mildred, the pale, shrewish tea-shop waitress, precisely because she is so common. Throughout my life, the women to whom I have been attracted more than casually have been both bright and talented. Only once have I ever been strongly attracted to a woman who, though by no means stupid, wasn’t exactly brainy. To be sure, I have also been attracted at first sight to a fair number of women of whom I knew nothing, but no sooner did I make their acquaintance than I discovered that they were–sure enough–bright and talented.

My problem with Maugham’s writing arises from the fact that this kind of obsession is not an experience I recognize, which makes it impossible for me to sympathize other than theoretically with those of his characters who are so enthralled. Try as I might, I can’t put myself in the place of a person like Philip Carey, the hero of Of Human Bondage, who seems to adore Mildred, the pale, shrewish tea-shop waitress, precisely because she is so common. Throughout my life, the women to whom I have been attracted more than casually have been both bright and talented. Only once have I ever been strongly attracted to a woman who, though by no means stupid, wasn’t exactly brainy. To be sure, I have also been attracted at first sight to a fair number of women of whom I knew nothing, but no sooner did I make their acquaintance than I discovered that they were–sure enough–bright and talented.

Is Maugham’s experience more common than mine? I doubt it. Yet there must be something about it that resonates with large numbers of people, since he was one of the most popular authors of the twentieth century. Or did his readers simply fail to register the idiosyncrasy of his manner of portraying love?

UPDATE: A friend writes:

How good to feel, when we have been rejected, that our beloved was a stupid scoundrel. Maugham avenges our amour propre.

TT: Almanac

“No man with any sense assumes that a woman’s words mean to her exactly what they mean to him.”

Rex Stout, The Mother Hunt