In 2006 Mrs. T and I successfully bid on a copy of “Apples on Table,” a 1923 lithograph by Marsden Hartley. Though he’s never been popular, Hartley was, with John Marin, one of this country’s first important modernist painters, and I’ve loved his work ever since I became familiar with it.

Needless to say, it had never occurred to me that I might actually be in a position to own a Hartley, but I discovered, very much to my surprise, that his lithographs were and are not only rare but obscure. He made only eighteen, most of them in smallish editions of twenty-five. They are scarcely ever exhibited–the only show devoted to Hartley’s prints, so far as I know, took place at the University of Kansas in 1972–and even those connoisseurs with a special interest in Hartley typically know little or nothing about them.

Needless to say, it had never occurred to me that I might actually be in a position to own a Hartley, but I discovered, very much to my surprise, that his lithographs were and are not only rare but obscure. He made only eighteen, most of them in smallish editions of twenty-five. They are scarcely ever exhibited–the only show devoted to Hartley’s prints, so far as I know, took place at the University of Kansas in 1972–and even those connoisseurs with a special interest in Hartley typically know little or nothing about them.

Because they’re so obscure, Hartley’s lithographs don’t cost anything like what you’d expect to pay for a pencil-signed print by a major American modernist. If memory serves, we paid $3,800 for “Apples on Table” in 2006, at a time when Hartley’s oil paintings were selling for as high as two million dollars. That’s not chump change for an impecunious critic, but we managed to scrape it together, and “Apples on Table” has hung over the dinner table in our Manhattan apartment ever since. It’s the first thing I see each time I unlock the front door after a long absence, and the sight of it never fails to warm my heart.

A couple of weeks ago, I received a form letter–an old-fashioned piece of snail mail, thank you very much–from Gail R. Levin, a Maine-based scholar who is working on a catalogue raisonné of Hartley’s lithographs. Levin’s goal is to track down every surviving copy of all eighteen prints, and to this end the auction house from which Mrs. T and I bought “Apples on Table” gave her our address.

The text of the letter is self-explanatory:

We plan to publish a handsomely illustrated, thoroughly researched and updated edition of Hartley’s stunning lithographic production….Would you please assist me in my research by filling out the attached data sheet for this and any other Hartley lithograph you might currently own?

I confess to having been thrilled by Levin’s letter. To be sure, several of the pieces that Mrs. T and I own can be found in existing catalogues raisonnés, but this will be the first time that our ownership of a work of art has been acknowledged by an art historian. That may not seem like a big deal to you, but I can’t help but be excited by it.

As I wrote six years ago apropos of my purchase of a Max Beerbohm caricature that is listed in Rupert Hart-Davis’ 1972 catalogue of Beerbohm’s drawings:

So there it was in black and white: my Max is officially known in the world of Beerbohmiana as “Hart-Davis 631.” It was publicly exhibited at the Leicester Galleries, Max’s London dealer, in 1913, and mentioned in a review of the show by Eddie Marsh, one of those semi-eminent Edwardian litterateurs who is constantly popping up in books, diaries, memoirs, and letters of the period. Presumably some even less eminent Edwardian bought it from the Leicester Galleries, for “Mr. Percy Grainger” has never been reproduced, nor was Hart-Davis able to establish its ownership as of 1972, the year he published his catalogue; it was invisible to Beerbohm scholars between 1913 and last week, when it came into my possession.

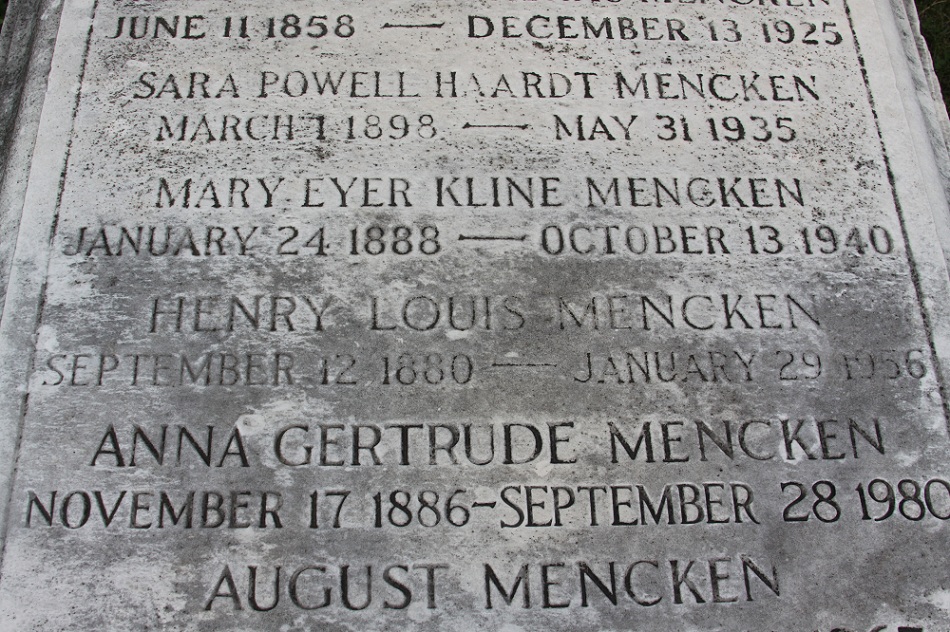

I felt a little shiver of excitement as I looked at the entry for Hart-Davis 631. My Max may not be famous, but it nonetheless has an official existence, of which I am now a part. If a younger scholar should someday take it upon himself to update the catalogue, he will add “OWNER Terry Teachout” to the entry for Hart-Davis 631. I find that a pleasant prospect. Even if The Skeptic and the Teachout Reader should crumble irrevocably into dust, I will live forever as a footnote to the lives of two men far greater than myself: not only did I rediscover the manuscript of A Second Mencken Chrestomathy among H.L. Mencken’s private papers and edit it for publication, but I was the first recorded owner of Hart-Davis 631.

Such frissons are, I believe, a legitimate part of the myriad delights of collecting art, even on a modest scale. Most of us, after all, never come to the attention of historians: we are members of the anonymous legions of those who, as Thomas Gray put it in his “Elegy in a Country Churchyard,” are born to blush unseen. Yet I suspect that anyone who writes a book feels at one time or another the longing that Mencken summed up in a private memorandum that he wrote on the first day of 1927: “I have done a great deal less than I wanted to do and a great deal less than I might have done if my equipment had been better, but this, at least, I have accomplished, and it is one of the principal desires of man: I have delivered myself from anonymity.”

Needless to say, I cannot speak the same words with anything remotely approaching H.L. Mencken’s self-confidence. To be sure, I like to think that Pops and The Skeptic might possibly survive me, but I’m not counting on it. Biographers write not for posterity but for their own generation, and rarely if ever are their efforts remembered in the long run save as footnotes to the subsequent efforts of their successors.

For this reason, I don’t think there’s much chance that anyone will remember me a hundred years from today, unless they happen to be perusing Gail Levin’s files and stumble across her research into the provenance of “Apples on Table,” in which case they will know that a copy of this exquisite hommage to Cézanne was once owned by an otherwise unknown couple named “Terry and Hilary Teachout.” By then Mrs. T and I will be long gone, and our handsome print will presumably be giving pleasure to a person or persons as yet unborn.

For this reason, I don’t think there’s much chance that anyone will remember me a hundred years from today, unless they happen to be perusing Gail Levin’s files and stumble across her research into the provenance of “Apples on Table,” in which case they will know that a copy of this exquisite hommage to Cézanne was once owned by an otherwise unknown couple named “Terry and Hilary Teachout.” By then Mrs. T and I will be long gone, and our handsome print will presumably be giving pleasure to a person or persons as yet unborn.

As for the two of us, we will, if nothing else, exemplify the last stanza of Philip Larkin’s great poem about the tombstone of a long-forgotten English couple:

The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be

Their final blazon, and to prove

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

So, too, shall it be for Mrs. T and me. Even if no stone should mark our final resting place, our marriage is now inscribed in the scholar’s book of life.