The phrase “senior moment” makes me want to retch. It is at once euphemistic and cute, a dreadful combination, and the fact that I am now old enough to experience with fair regularity the transitory lapses of memory to which it refers doesn’t make it any more palatable.

A few weeks ago Mrs. T and I were driving from Connecticut to Maine when I suddenly found myself incapable of remembering the name of Ralph Peer. Not only does Peer figure prominently in Pops, but an old friend of mine once planned to write his biography, a book whose subtitle I had no trouble recalling, even though the book itself never got finished. I even managed to reel off an impromptu outline of Peer’s career and achievements. The only thing I couldn’t come up with was his name. After some twenty-odd minutes of frustration, I boiled over, steered into a rest stop, booted up my laptop, and pulled up the chapter from Pops in which I wrote about Peer. No sooner did his name flash on the screen than I felt as if a boil in my brain had been lanced.

A few weeks ago Mrs. T and I were driving from Connecticut to Maine when I suddenly found myself incapable of remembering the name of Ralph Peer. Not only does Peer figure prominently in Pops, but an old friend of mine once planned to write his biography, a book whose subtitle I had no trouble recalling, even though the book itself never got finished. I even managed to reel off an impromptu outline of Peer’s career and achievements. The only thing I couldn’t come up with was his name. After some twenty-odd minutes of frustration, I boiled over, steered into a rest stop, booted up my laptop, and pulled up the chapter from Pops in which I wrote about Peer. No sooner did his name flash on the screen than I felt as if a boil in my brain had been lanced.

I don’t lose any sleep worrying about such transient episodes–I’ve been having them for the better part of a decade, after all–but I do feel a bit rueful about them on occasion. I used to have a near-perfect memory, and now I don’t. Nor can I deny that I occasionally find myself haunted by the thought that I might someday be deprived by illness of the whole of my memory, which would mean that I would cease to be myself. I’ve never been close to anyone who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, but one of my mother’s oldest friends was stricken with it a number of years ago, and I looked on in horror as he gradually withdrew into a genial but impenetrable cloud of unknowingness.

“Old age is a shipwreck,” Charles de Gaulle wrote, and at fifty-four I am close enough to my own old age to wonder what it will be like. I’d like to think that Charles Dickens foretold it when he assured the readers of Barnaby Rudge that “Father Time is not always a hard parent, and, though he tarries for none of his children, often lays his hand lightly on those who have used him well.” But I know well–too well–that it isn’t always like that.

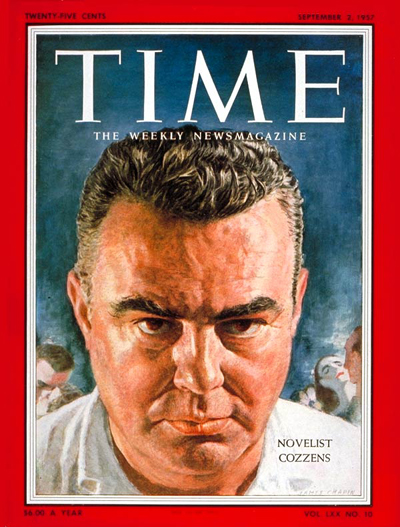

James Gould Cozzens, a thoroughly hardheaded novelist who took care never to turn his face from reality, wrote in By Love Possessed a thumbnail sketch of an increasingly absentminded octogenarian lawyer that is all the more chilling for its complete lack of melodrama:

James Gould Cozzens, a thoroughly hardheaded novelist who took care never to turn his face from reality, wrote in By Love Possessed a thumbnail sketch of an increasingly absentminded octogenarian lawyer that is all the more chilling for its complete lack of melodrama:

Incidentally, Arthur Winner must reflect, Noah really ought to stop driving a car; but who would venture to say so? Who would call his attention to his malady without a cure–the yellow leaves, or none, or few; the twilight of the day; in the ashes, the doubtful glow of the expiring fire? This was the time of year on which Noah was congratulated; these were the mental powers whose persistence was often and admiringly mentioned. Remarkable? Yes; so remarkable that admiration posed the query of astonishment: Can such things be?

To that question, a question must be returned. The answer depended on what you meant. In his own field, on those probate and fiduciary matters to which Noah had given a lifetime, half a century, Noah could sound as acute and sagacious as ever. There, nothing unknown or new could now confront him; the right answers, formulated over and over so often that he had them by heart, came of themselves. If unimpaired mental powers was construed to mean competence to do today that job of ten years ago on the Decedents Estates Law that Willard Lowe had praised, Arthur Winner would be inclined to agree that Noah, unequaled in technical knowledge, unexcelled in practical estate and trust management, with so much of the special sort of legal experience needed in this special sort of work, probably still kept that competence. If, by unimpaired mental powers, you meant an unaffected judgment, a continuing sound sense of proportion, a reliable balance, a firmness of command in coming to decisions and a promptitude in acting on them–what was to be said about that?

What, indeed?