William Jewell College, my alma mater, is the home of one of the finest performing-arts series in America, the Harriman-Jewell Series. Among countless noteworthy things, the Harriman-Jewell Series presented Luciano Pavarotti in his professional recital debut in 1973. During my student days, I saw under its auspices performances by Pavarotti, Birgit Nilsson, Itzhak Perlman, Leontyne Price, Mstislav Rostropovich, Rudolf Serkin, Frederica von Stade, Twyla Tharp, and Beverly Sills–all of which I attended for free.

Richard Harriman, the man who co-founded and directed the series and after whom it would later be named, graduated from Jewell in 1953 and joined its English faculty in 1962. Three years later he decided that the college ought to be in the business of presenting great performances. He extracted three thousand dollars from the administration and proceeded to book Edward Villella, Patricia MacBride, and Jan Peerce. Not long after that, Liberty, Missouri, the suburb of Kansas City where William Jewell College is located, had become known throughout America as the place where world-famous musicians tried out the programs they would later perform in New York.

Richard Harriman, the man who co-founded and directed the series and after whom it would later be named, graduated from Jewell in 1953 and joined its English faculty in 1962. Three years later he decided that the college ought to be in the business of presenting great performances. He extracted three thousand dollars from the administration and proceeded to book Edward Villella, Patricia MacBride, and Jan Peerce. Not long after that, Liberty, Missouri, the suburb of Kansas City where William Jewell College is located, had become known throughout America as the place where world-famous musicians tried out the programs they would later perform in New York.

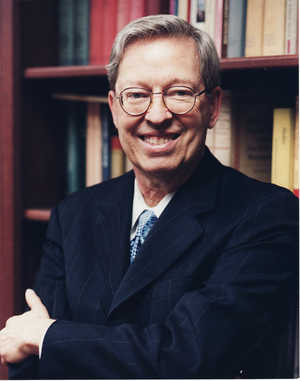

Mr. Harriman–I never got used to calling him Dick, not even after I grew up, moved to New York, and became a full-time critic of the arts–was the most genial of impresarios, a famously soft-spoken man who never had a bad word to say about anyone, at least not in my hearing. Nor did I ever hear anyone say a bad word about him. He was kind, sweet-natured, and impeccably tasteful in every aspect of his life and work. That he took an interest in me when I was an undergraduate was one of the luckiest breaks in a life that has been full of good fortune.

In addition to giving away free tickets to any student willing to line up and claim them, Mr. Harriman took a group of arts-conscious students to New York each winter and shepherded them to performances of every imaginable kind. I went on that trip in December of 1975, and wrote about it years later in a memoir of my youth:

Rummaging through my mother’s cupboard the other day, I found a manila envelope full of souvenirs of my visit to New York. There was my program from Harold Prince’s Broadway production of Candide; there were Lincoln Center and Radio City Music Hall and Mikhail Baryshnikov, fresh out of Rusia, soaring across the stage of the Uris Theater; there was a memorandum scrawled in an unformed hand on Waldorf-Astoria stationery (when you traveled with Mr. Harriman, you traveled first-class) telling where I had eaten dinner each night. The food I ate dazzled me as much as the sights I saw, for I had been raised on Kraft Dinner and Chef Boy-Ar-Dee pizza in a box, and the act of ordering vichyssoise from a haughty waiter at “21” very nearly made me swoon.

In later years I would occasionally run into Mr. Harriman in the lobby of a Manhattan theater or concert hall. We would swap snippets of performing-arts gossip, and I always tried to conduct myself not as a former student but as a colleague. It was, of course, an act, and a poor one. He had been present at the creation of my career, and it was impossible for me to talk to him without being intensely and inhibitingly aware of how very much I owed him.

It would have been no more possible for me to thank him to his face for what he had done for me, but I was able to do it from a safe distance when Achieve, William Jewell’s alumni magazine, asked me to write a few words of tribute when his series celebrated its fortieth anniversary and was renamed the Harriman Arts Program. This is what I wrote:

Cézanne called the Louvre “the book in which we learn to read.” The Harriman Arts Program was the book in which I learned to see, hear, and love the performing arts. It gave me a golden yardstick of taste–one I still use to this day.

Mr. Harriman died this afternoon at the age of seventy-seven. I bless and revere his memory.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

Your essay reminds me of something very important that is easy to forget: that a civilization’s art and culture are preserved and kept alive when related to as a highly personal and carefully selected gift from one generation to the next, from an individual to a valued friend. This is exactly what Harriman gave to his students and general audiences.

So it was. Well said.