It’s become chic in literary circles to celebrate June 16 as Bloomsday, the date on which the events chronicled in James Joyce’s Ulysses supposedly took place in Dublin. But celebrations notwithstanding, the fact remains that Ulysses is more admired than read–and that Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s other major novel, isn’t even read. Few people are prepared to grapple with its fantastic verbal complications, any more than they’re prepared to grapple with the musical hypercomplexities of an exercise in atonal modernism like Pierre Boulez’s Le marteau sans maître.

I thought of Joyce at once when a musician friend drew my attention the other day to a 1988 paper by Fred Lerdahl called Cognitive Constraints on Compositional Systems. Lerdahl, a tonal composer who has studied cognitive psychology, believes that certain kinds of modern music are too complicated for the human brain to process, and will therefore never find an audience. It immediately occurred to me when I read his paper that the same inborn limitations on intelligibility might apply to practitioners of other art forms–and no sooner did I come to that conclusion than I felt the first stirrings of a “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal.

I thought of Joyce at once when a musician friend drew my attention the other day to a 1988 paper by Fred Lerdahl called Cognitive Constraints on Compositional Systems. Lerdahl, a tonal composer who has studied cognitive psychology, believes that certain kinds of modern music are too complicated for the human brain to process, and will therefore never find an audience. It immediately occurred to me when I read his paper that the same inborn limitations on intelligibility might apply to practitioners of other art forms–and no sooner did I come to that conclusion than I felt the first stirrings of a “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal.

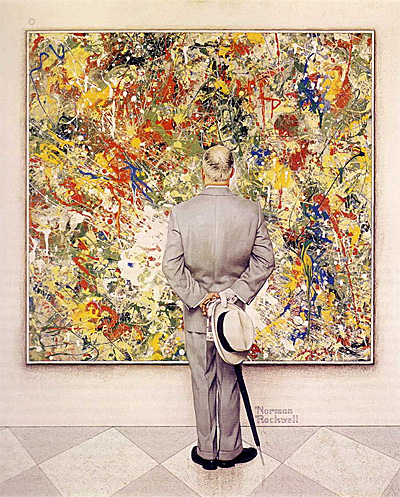

Are our brains simply not big enough to process the prose of Joyce or the music of Boulez? And if not, then why have such similarly complex artistic creations as the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock succeeded in finding an appreciative popular audience? To find out, pick up a copy of Saturday’s Journal and see what I have to say.

UPDATE: Read the whole thing here.

* * *

James Joyce reads an excerpt from Finnegans Wake:

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog