“Struggling young repertory actors believe too fervently in themselves and their prospects ever to entertain the conscious thought that their backers can suffer–or, at any rate, the thought that their backers can suffer in anything but a noble cause.”

Patrick Hamilton, Mr. Stimpson and Mr. Gorse

Archives for April 2010

TT: Food for thought

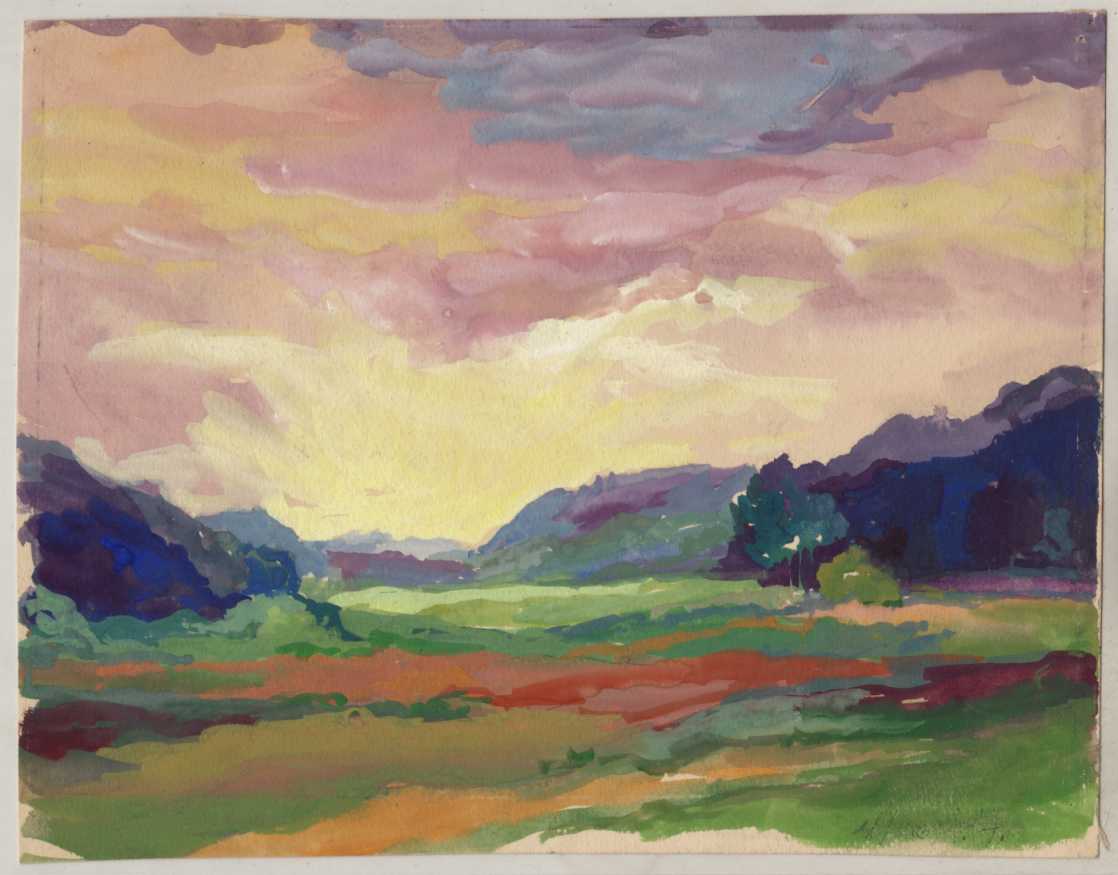

Who painted this unsigned watercolor?

If you need a hint–and you almost certainly will–the painter once made the following remark:

We should never judge artists by their political views. The imagination they need for their work deprives them of the ability to think in realistic terms.

Care to venture a guess? If not, search for the quote and you’ll find out the answer….

TT: Almanac

“But a long time ago I made me a rule: I let people do what they want to do.”

Louis L’Amour, Hondo

TT: Low-rent Apartment

The Wall Street Journal‘s much-discussed New York section was rolled out this morning. As part of the general ballyhoo, I’ve been asked to write a second weekly drama column for the Journal, this one specifically for the new section. The new column won’t run on a specific day, but will be published on the morning after the opening of whatever show I happen to be reviewing. Subscribers to the national edition won’t see it, alas, but anybody can read it on line.

My inaugural column is about the Broadway revival of Promises, Promises, which I regret to say is a major disappointment. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

When a hit musical drops out of sight for nearly four decades, there’s usually a reason. In the case of “Promises, Promises,” which is being revived for the first time on Broadway since the original production closed there after a 1,281-performance run, the reason is obvious: It’s no good. Nor is Rob Ashford’s big-budget mounting likely to win many new friends for the 1968 Burt Bacharach-Hal David-Neil Simon adaptation of Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment.” Not only is it dully staged, but it’s so miscast that even Kristin Chenoweth, normally one of Broadway’s hottest commodities, looks like she showed up at the wrong theater.

To be sure, it’s easy to see why Messrs. Bacharach, David and Simon thought it a good idea to turn “The Apartment” into a musical. Wilder’s 1960 movie is one of the sharpest-witted romantic comedies ever filmed, a sweet-and-sour tale of workplace fornication in which every laugh has a sting in the tail. It was also perfectly cast, with Jack Lemmon playing the role of C.C. Baxter, a corporate hireling who makes his apartment available to Fred MacMurray, his married boss, for after-hours trysts with Shirley MacLaine, the delectable elevator operator whom both men crave.

To be sure, it’s easy to see why Messrs. Bacharach, David and Simon thought it a good idea to turn “The Apartment” into a musical. Wilder’s 1960 movie is one of the sharpest-witted romantic comedies ever filmed, a sweet-and-sour tale of workplace fornication in which every laugh has a sting in the tail. It was also perfectly cast, with Jack Lemmon playing the role of C.C. Baxter, a corporate hireling who makes his apartment available to Fred MacMurray, his married boss, for after-hours trysts with Shirley MacLaine, the delectable elevator operator whom both men crave.

That’s where the trouble starts with “Promises, Promises.” Problem No. 1: Ms. Chenoweth plays Fran Kubelik, the shopworn waif who is so devastated by her lover’s faithlessness that she takes an overdose of sleeping pills. I’m one of Ms. Chenoweth’s staunchest admirers, but her gifts do not include the ability to suggest vulnerability, and it is impossible to imagine that so self-assured a woman would even contemplate suicide, much less attempt it. As a result, her performance is dramatically unbelievable…

This brings us to the deficiencies of the show proper. In the film, Baxter supplies an introductory narration that sets up the plot, then lets the viewer figure the rest out for himself. In the musical, he narrates from start to finish, a bad idea that kills the momentum stone dead and is made worse by Mr. Simon’s habit of stuffing his speeches full of jokes that might been funny in 1968 but are now about as stylish as a Buick with fins.

As for the score, it consists of a string of chirpy soft-rock ballads like the title tune and “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” that were heard around the clock on AM radio back in the days of Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass (which doubtless explains why the original production of “Promises, Promises” was so huge a hit). One of them, “A House Is Not a Home,” is a beautifully turned piece of work that has since been taken up by such jazz greats as Sarah Vaughan and Bill Evans. The others are so similar-sounding as to approach indistinguishability….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

UPDATE: A reader advised me this morning that the original online version of this column was behind the Journal‘s paywall. I now have a link in place that should be accessible to everyone.

TT: Mamet’s top ten

I expect that David Mamet’s Theatre, which was published last week, is going to stir up a stink, and I plan to write about it at length at some point in the future. For now, though, I want to pass on the following paragraphs:

I expect that David Mamet’s Theatre, which was published last week, is going to stir up a stink, and I plan to write about it at length at some point in the future. For now, though, I want to pass on the following paragraphs:

Here are my choices for Great American Plays: First, Our Town, then The Front Page, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, A Streetcar Named Desire, All My Sons, and Doubt. One might also mention The Time of Your Life, The Boys in the Band, The Best Man, and The Women.

What do these plays have in common? They are intensely American. That is, they both treat American issues and are written in an American idiom closer to real poetry than to prose.

That is a damned interesting list, and an equally interesting explanation. My own list, needless to say, would look different–but the overlap would be considerable.

TT: Almanac

“The very object of an art, the principle of its artifice, is precisely to impart the impression of an ideal state in which the man who reaches it will be capable of spontaneously producing, with no effort of hesitation, a magnificent and wonderfully ordered expression of his nature and our destinies.”

Paul Valéry, “Remarks on Poetry”

BOOK

David Mamet, Theatre (Faber & Faber, $22). In this hard-nosed little book, the author of American Buffalo and Glengarry Glen Ross concisely sets forth his explanations of what theater is, how it works, why most directors and all critics are idiots, and why people who don’t write plays like David Mamet are basically wasting their time. He also finishes the job of outing himself as a libertarian-flavored not-quite-conservative. Since Mamet is also one of the major American playwrights of the twentieth century, all this is of obvious interest to anyone who cares about theater, and it’s expressed so compellingly (if repetitiously) that you can’t help but get swept up in the current of the author’s absolute self-assurance. You may not like Theatre, but you’ll learn from it (TT).

CD

Pat Metheny, Orchestrion (Nonesuch). The most influential jazz guitarist of his generation hooks up a roomful of solenoid-controlled acoustic musical instruments to his electric guitar, turns them into the world’s biggest one-man band, and causes them to play an albumful of ear-ticklingly lovely original compositions. Go here to see Metheny talk about the technology behind this fascinating project–but by all means listen first (TT).