This meme, started by Tyler Cowen and picked up by, among others, Jenny Davidson and Ross Douthat, has piqued my interest. Here goes:

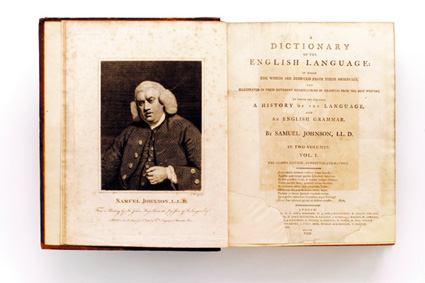

• W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson. It was this modern exemplar of the biographer’s art, not Boswell’s Life, that introduced me to the man who became and remained my hero. Not only did Dr. Johnson’s clear-eyed, cant-free view of human nature help me to see the world as it is, but I found his lifelong struggle against his own inborn defects of temperament to be powerfully inspiring. I still do, and probably always will.

• W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson. It was this modern exemplar of the biographer’s art, not Boswell’s Life, that introduced me to the man who became and remained my hero. Not only did Dr. Johnson’s clear-eyed, cant-free view of human nature help me to see the world as it is, but I found his lifelong struggle against his own inborn defects of temperament to be powerfully inspiring. I still do, and probably always will.

• Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes. I came to Conrad relatively late, which is doubtless a good thing, since he is not for the young, whose inexperience prevents them from grappling with his cinder-black disillusion. Together with The Secret Agent, its companion piece, Under Western Eyes clarified my inchoate beliefs about the relationship between politics and idealism. I wrote about both books fourteen years ago in a New York Times op-ed piece published after it became known that the Unabomber was a Conrad fan (though not a very intelligent one). One line says it all: “He was a dangerous man–a convinced man.”

• James Gould Cozzens, Guard of Honor. All but forgotten today, Guard of Honor is the greatest novel of World War II to be written by an American. Reading it made me a stoic, or at least as much of one as I think it suitable for a gentleman to be.

• Edwin Denby, Dance Writings. Missing from this list, somewhat to my surprise, is any book having to do with music. Needless to say, I read hundreds of books about music in my youth, but none of them, so far as I know, shaped the way that I see the world–they merely pointed me toward the composers and performers whose work did the shaping. Edwin Denby did that for me with dance, but he also taught me how a newspaper critic can write about a complex art form in a serious yet accessible way. Even though my style is nothing like his, he remains my journalistic beau ideal.

• Moss Hart, Act One: An Autobiography. If you want to become hopelessly stagestruck, read Act One in high school. It never occurred to me as a theater-crazy teenager that I would someday become a New York drama critic, much less write an opera libretto, but I suspect that my adolescent reading of Hart’s half-realistic, half-starry-eyed memoir of the road that led him to Broadway planted the seeds that bore fruit half a lifetime later.

• Moss Hart, Act One: An Autobiography. If you want to become hopelessly stagestruck, read Act One in high school. It never occurred to me as a theater-crazy teenager that I would someday become a New York drama critic, much less write an opera libretto, but I suspect that my adolescent reading of Hart’s half-realistic, half-starry-eyed memoir of the road that led him to Broadway planted the seeds that bore fruit half a lifetime later.

• Randall Jarrell, Pictures from an Institution: A Comedy. This coruscatingly brilliant comic novel “showed” me the world of the intellect in much the same way that Act One showed me the world of the theater, but with a big difference: Jarrell’s sharp-witted snapshots of academic life did more than anything else to prevent me from going to graduate school. It’s possible that he did me a disservice–I discovered years later that I loved teaching–but I think it at least as likely that he saved me from a life of chronic frustration.

• George Orwell, The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters. I found an already-battered paperback edition of this four-volume set in the Book Bug, a used-book store in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, some forty years ago. It remains on my shelf to this day. Orwell was the first nonfiction writer whose commonsense style spoke to me, and whose work gave me a sense of the kind of writing that I wanted to do. I also was influenced by his willingness to engage with the world in essentially moralistic terms, even though his perspective was entirely secular.

• Fairfield Porter, Art in Its Own Terms: Selected Criticism, 1935-1975. Porter was a great painter (though he is not yet widely recognized as such) who was also a great critic. On the same day that I first looked at one of his paintings, “Wheat,” I bought a copy of this book in the shop of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It taught me how to see–and how to think about what I saw. It also made me a better critic.

• Fairfield Porter, Art in Its Own Terms: Selected Criticism, 1935-1975. Porter was a great painter (though he is not yet widely recognized as such) who was also a great critic. On the same day that I first looked at one of his paintings, “Wheat,” I bought a copy of this book in the shop of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It taught me how to see–and how to think about what I saw. It also made me a better critic.

• Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men. The most insightful of all American political novels, though not so much about the political process (if you want to understand that, read Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent) as about the deep-seated passions that drive high-minded men to seek power over one another. In a well-regulated society, you wouldn’t be allowed to register to vote until you’d read it.

• Evelyn Waugh, Black Mischief. I’ve read a great deal about politics in my lifetime, but no book, not even All the King’s Men, did more to shape my political philosophy, such as it is, than this ferociously funny parable of the thinness of the crust of ice on which civilization rests.