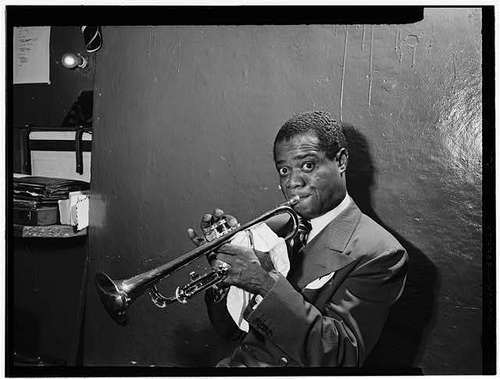

So far as I know, everybody in and around jazz liked Herb Ellis, both as a guitarist and as a man. His no-nonsense style was a big part of what made the Oscar Peterson Trio so solid and satisfying in its piano-guitar-bass version, and his longtime partnership with Peterson and Ray Brown continues to be admired to this day, not least by those who, like me, have had the exhilarating pleasure of playing in a hard-swinging rhythm section.

Alas, there isn’t much film of the Peterson Trio on YouTube, but this 1958 version of “A Gal in Calico” has been making the rounds ever since the announcement of Ellis’ death on Sunday (he suffered from Alzheimer’s disease). It’s a fine way to remember a superior artist:

Archives for March 2010

TT: Snapshot

“Another Day Another Doormat,” a 1959 animated cartoon written by Tom Morrison and directed by Al Kouzel:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Entry from an unkept diary

• Unlike most middle-aged bloggers, I’ve been hearing from the public for the whole of my adult life–I started writing newspaper criticism while I was still an undergraduate–and so it’s nothing new when strangers write to tell me that I’m a despicable beast. The emergence of cyberspace, however, has made it vastly easier for people to express their opinions of public and semi-public figures, either directly via e-mail or by posting a comment or review somewhere on the Web, which means that there’s a whole lot more to read today than there was in, say, 1980.

I don’t go out of my way to read everything that gets written about me, but I do see a fair amount of it in the ordinary course of my working day, and it never fails to strike me that a considerable number of the people who write about the pieces that they read, whether by me or anyone else, haven’t actually read them. Or, to be exact, they read until they encounter a statement with which they disagree, at which precise moment they stop reading, boil over, and start clicking away at their keyboards with what they imagine to be annihilating fury.

I don’t go out of my way to read everything that gets written about me, but I do see a fair amount of it in the ordinary course of my working day, and it never fails to strike me that a considerable number of the people who write about the pieces that they read, whether by me or anyone else, haven’t actually read them. Or, to be exact, they read until they encounter a statement with which they disagree, at which precise moment they stop reading, boil over, and start clicking away at their keyboards with what they imagine to be annihilating fury.

It goes without saying that the opinions of such folk aren’t worth knowing. But I wonder: are most people like that? In other words, might it be normal for the average human being to be incapable of considering, however briefly, the possible validity, however partial, of opinions in any way contrary to his own? I hesitate to suggest such a dispiriting notion, but the older I grow, the more likely it seems.

H.L. Mencken said it: “Public opinion, in its raw state, gushes out in the immemorial form of the mob’s fear. It is piped into central factories, and there it is flavoured and coloured and put into cans.” That was in Notes on Democracy, published in 1926. Plus ça change…

TT: Almanac

“Reading means borrowing.”

G.C. Lichtenberg, Reflections

TT: Apologies in advance

It may not seem like it, but I read all of my incoming mail, and do my best to answer it as well. I just spent a couple of hours chewing through a pile of accumulated messages. Alas, there are times when I simply get too much mail to keep up, especially when I write Wall Street Journal columns that touch a nerve. I know that some of you have sent me e-mails that slipped between the cracks, and I hope you’ll forgive me if you fail to get a response, timely or otherwise. Please try again–I really do love hearing from you!

It may not seem like it, but I read all of my incoming mail, and do my best to answer it as well. I just spent a couple of hours chewing through a pile of accumulated messages. Alas, there are times when I simply get too much mail to keep up, especially when I write Wall Street Journal columns that touch a nerve. I know that some of you have sent me e-mails that slipped between the cracks, and I hope you’ll forgive me if you fail to get a response, timely or otherwise. Please try again–I really do love hearing from you!

As for snail mail, here are four things I should have said long ago:

• Remember that it’s much easier for me to answer e-mail than snail mail!

• I regret that I can no longer honor new requests to sign copies of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong and return them to you by mail. Of course I’ll happily sign your copy in person, but the oppressive volume of snail mail that I now receive at my New York address, coupled with the rigors of my traveling schedule, has made it impossible for me to do anything more than that.

• I throw away unsolicited review copies of books and compact discs. This is a small apartment, and I can’t cope with packages that come over the transom. Again, forgive me for being so blunt, but I’m the one that has to clean up the mess every day (I don’t have a secretary). I’m sure your self-produced album is wonderful, but there’s no chance that I’m going to listen to it, much less write about it, so please don’t bother.

• If you’re a publicist who writes to me here or at my Wall Street Journal mailbox instead of at my private e-mail address, you’re wasting your time. Mass-mailed press releases sent to my blogbox are deleted unread, and the Journal only forwards reader mail, not press releases, to my private address. Experienced publicists either know how to get in touch with me directly or can find out–all it takes is a little digging–and should do so.

TT: It’s that man again

Here’s how busy I’ve been: I completely forgot that C-SPAN would be airing my January appearance at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C., during which I read from and answered questions about Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong. I couldn’t figure out why the Amazon sales rank for Pops had been spiking unpredictably in recent days. Then my mother told me that a neighbor called her on Saturday morning and said, “Turn on your TV–Terry’s on it!”

Here’s how busy I’ve been: I completely forgot that C-SPAN would be airing my January appearance at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C., during which I read from and answered questions about Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong. I couldn’t figure out why the Amazon sales rank for Pops had been spiking unpredictably in recent days. Then my mother told me that a neighbor called her on Saturday morning and said, “Turn on your TV–Terry’s on it!”

If you’re curious, you can watch the telecast by going here. To be perfectly frank, I didn’t think that it was one of my better performances, but the folks at Politics and Prose claimed to feel otherwise, so I invite you to decide for yourself.

TT: Almanac

“Books are fatal: they are the curse of the human race. Nine-tenths of existing books are nonsense, and the clever books are the refutation of that nonsense. The greatest misfortune that ever befell man was the invention of printing.”

Benjamin Disraeli, Lothair

TT: Ten books which influenced my view of the world

This meme, started by Tyler Cowen and picked up by, among others, Jenny Davidson and Ross Douthat, has piqued my interest. Here goes:

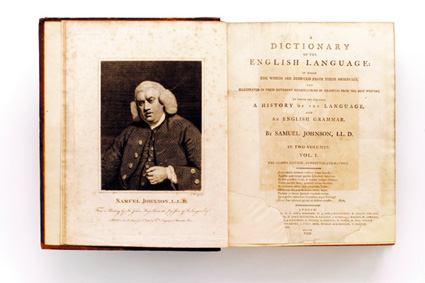

• W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson. It was this modern exemplar of the biographer’s art, not Boswell’s Life, that introduced me to the man who became and remained my hero. Not only did Dr. Johnson’s clear-eyed, cant-free view of human nature help me to see the world as it is, but I found his lifelong struggle against his own inborn defects of temperament to be powerfully inspiring. I still do, and probably always will.

• W. Jackson Bate, Samuel Johnson. It was this modern exemplar of the biographer’s art, not Boswell’s Life, that introduced me to the man who became and remained my hero. Not only did Dr. Johnson’s clear-eyed, cant-free view of human nature help me to see the world as it is, but I found his lifelong struggle against his own inborn defects of temperament to be powerfully inspiring. I still do, and probably always will.

• Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes. I came to Conrad relatively late, which is doubtless a good thing, since he is not for the young, whose inexperience prevents them from grappling with his cinder-black disillusion. Together with The Secret Agent, its companion piece, Under Western Eyes clarified my inchoate beliefs about the relationship between politics and idealism. I wrote about both books fourteen years ago in a New York Times op-ed piece published after it became known that the Unabomber was a Conrad fan (though not a very intelligent one). One line says it all: “He was a dangerous man–a convinced man.”

• James Gould Cozzens, Guard of Honor. All but forgotten today, Guard of Honor is the greatest novel of World War II to be written by an American. Reading it made me a stoic, or at least as much of one as I think it suitable for a gentleman to be.

• Edwin Denby, Dance Writings. Missing from this list, somewhat to my surprise, is any book having to do with music. Needless to say, I read hundreds of books about music in my youth, but none of them, so far as I know, shaped the way that I see the world–they merely pointed me toward the composers and performers whose work did the shaping. Edwin Denby did that for me with dance, but he also taught me how a newspaper critic can write about a complex art form in a serious yet accessible way. Even though my style is nothing like his, he remains my journalistic beau ideal.

• Moss Hart, Act One: An Autobiography. If you want to become hopelessly stagestruck, read Act One in high school. It never occurred to me as a theater-crazy teenager that I would someday become a New York drama critic, much less write an opera libretto, but I suspect that my adolescent reading of Hart’s half-realistic, half-starry-eyed memoir of the road that led him to Broadway planted the seeds that bore fruit half a lifetime later.

• Moss Hart, Act One: An Autobiography. If you want to become hopelessly stagestruck, read Act One in high school. It never occurred to me as a theater-crazy teenager that I would someday become a New York drama critic, much less write an opera libretto, but I suspect that my adolescent reading of Hart’s half-realistic, half-starry-eyed memoir of the road that led him to Broadway planted the seeds that bore fruit half a lifetime later.

• Randall Jarrell, Pictures from an Institution: A Comedy. This coruscatingly brilliant comic novel “showed” me the world of the intellect in much the same way that Act One showed me the world of the theater, but with a big difference: Jarrell’s sharp-witted snapshots of academic life did more than anything else to prevent me from going to graduate school. It’s possible that he did me a disservice–I discovered years later that I loved teaching–but I think it at least as likely that he saved me from a life of chronic frustration.

• George Orwell, The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters. I found an already-battered paperback edition of this four-volume set in the Book Bug, a used-book store in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, some forty years ago. It remains on my shelf to this day. Orwell was the first nonfiction writer whose commonsense style spoke to me, and whose work gave me a sense of the kind of writing that I wanted to do. I also was influenced by his willingness to engage with the world in essentially moralistic terms, even though his perspective was entirely secular.

• Fairfield Porter, Art in Its Own Terms: Selected Criticism, 1935-1975. Porter was a great painter (though he is not yet widely recognized as such) who was also a great critic. On the same day that I first looked at one of his paintings, “Wheat,” I bought a copy of this book in the shop of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It taught me how to see–and how to think about what I saw. It also made me a better critic.

• Fairfield Porter, Art in Its Own Terms: Selected Criticism, 1935-1975. Porter was a great painter (though he is not yet widely recognized as such) who was also a great critic. On the same day that I first looked at one of his paintings, “Wheat,” I bought a copy of this book in the shop of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It taught me how to see–and how to think about what I saw. It also made me a better critic.

• Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men. The most insightful of all American political novels, though not so much about the political process (if you want to understand that, read Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent) as about the deep-seated passions that drive high-minded men to seek power over one another. In a well-regulated society, you wouldn’t be allowed to register to vote until you’d read it.

• Evelyn Waugh, Black Mischief. I’ve read a great deal about politics in my lifetime, but no book, not even All the King’s Men, did more to shape my political philosophy, such as it is, than this ferociously funny parable of the thinness of the crust of ice on which civilization rests.