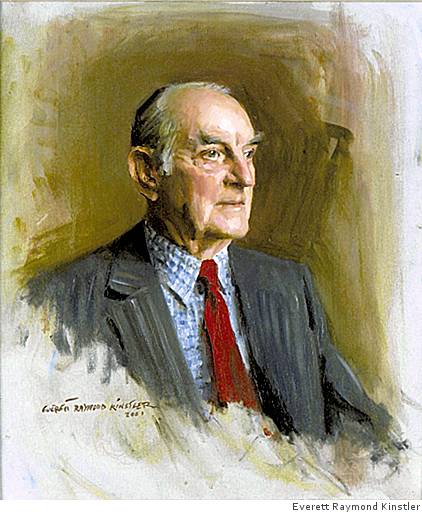

Louis Auchincloss, who has died at the august age of 92, was a novelist whom I admired, albeit with significant reservations.

Louis Auchincloss, who has died at the august age of 92, was a novelist whom I admired, albeit with significant reservations.

Auchincloss hit the high C once, with The Rector of Justin. Only one of his other novels, The Embezzler, has anything like the focus and intensity of that excellent book, and it runs a distant second. His other novels are watery by comparison, so much so that it’s tempting to call him a man of one book, though in fact he wrote many books, all of them serious and well crafted and not a few of them gratifyingly readable. Still, it’s no mean thing to write even one novel of significance, and The Rector of Justin, to my mind, definitely qualifies.

I wrote about Auchincloss twice, in 1993 and 1995. Here’s some of what I had to say on those two occasions:

Rarely is it possible to single out the stupidest thing ever written about someone, but in the case of Louis Auchincloss, the booby prize undoubtedly goes to a piece published a quarter-century ago in the New York Review of Books. The author, boggling at the undeniable fact that Auchincloss’ novels are all about New York’s moneyed families, wrote, “I can believe the upper class is human…but fiction seems the wrong medium for the privileged life, which belongs, if anywhere, in the spreads of Country Life or the New York Times society page, or in the moments of awed intrusion that TV likes to purvey.” So long, Henry James! Bye-bye, Marcel Proust!…

Auchincloss is worth reading about not only because he is a good writer but also because his life is so perfectly emblematic of the class that writer-director Whit Stillman, in the movie Metropolitan, called the “UHB”–urban haute bourgeoisie. Auchincloss attended Groton School, Yale University and the University of Virginia Law School, put in a couple of years at Sullivan & Cromwell, served with distinction in World War II, returned to New York to find a place in the trusts and estates department of Hawkins, Delafield & Wood, married well and lived happily ever after. His only deviation from form was a passion for literature that led him to do something wildly uncharacteristic for a white-shoe lawyer: He became a part-time professional writer.

Auchincloss broke into print two years after the war and since that time has turned out roughly a book a year. He writes about what he knows: “I especially want to portray things into which I’ve been fortunate enough to gain insight, that is, the decline of a class. WASPs have not lost their power, but they have lost their monopoly on power.”

All his novels and short stories deal in one way or another with this theme, so much so that many critics have been put off by his exclusive interest in the WASP world–or, to be more exact, by his comparatively untroubled acceptance of its imperatives: “I have always suffered from the suspicion not so much that I write about the wrong people (look at the success of [John] O’Hara and [John P.] Marquand!) but that I write about the wrong people in the wrong way. Perhaps I tend to accept the status quo more than seems acceptable.”

This is a shrewd remark, and it suggests one possible reason why Auchincloss has never written an absolutely first-rate novel: He seems too happy. After a successful round of psychoanalysis (apparently there are such things) in the early fifties, Auchincloss accepted himself without reservation. If this account of his life is accurate, he is an obsession-free, comparatively uncomplicated man whose urge to write is rooted more in his desire to record the splendors and miseries of a social class than in any private passions of his own.

It is surely no coincidence that Auchincloss’s best novel, the 1964 The Rector of Justin, deals with the only episode in his life that appears to have scarred him: his years at Groton. In The Rector of Justin, Auchincloss fuses his cold-eyed inside knowledge of how the world of privilege really works with his angry memories of “being back amid the varnished walls surrounded by boys who are waiting to kill the smallest aspiration.” The result is a novel of considerable power and insight, perhaps the best thing ever written about the American prep school ethos….

He will be missed.