• I’ve been sprinting on a treadmill since The Letter went into rehearsal last summer, and the unexpected success of Pops has turned the speed up several notches. I like what’s happening to me, but I don’t care for some of the side effects.

At the moment I have five jobs, all of them variously demanding: drama critic and arts journalist, biographer, opera librettist, itinerant book-flogger, and visiting scholar-in-residence. One unforeseen consequence of my near-ceaseless activity is that I’ve temporarily lost the power to relax. I wake up at six-thirty each morning as if prodded by a prison guard, and I find it difficult to sit and do nothing on the rare occasions when it’s possible for me to do so. I’m not listening to much music, either, though I can still read for pleasure, especially on trains. Only the other day I wolfed down FDR’s Deadly Secret like a fast-food burger on the Acela Express from Washington to New York. For the most part, though, I seem to be going directly from taxi to airport to hotel to lunch to interview to dinner to show to bed, then starting the cycle over again.

Conspicuously absent from this hectic sequence of events is contemplation. Though I now know for sure what my next biography will be and also have a pretty good idea of what my next opera libretto is likely to be, I haven’t had much time in recent weeks to stare into space and let my imagination play freely over these projects, much less to spin others out of the air. I actually found myself working on an airplane last night instead of gazing out the window and reveling in the view, which is what I usually do when flying.

Conspicuously absent from this hectic sequence of events is contemplation. Though I now know for sure what my next biography will be and also have a pretty good idea of what my next opera libretto is likely to be, I haven’t had much time in recent weeks to stare into space and let my imagination play freely over these projects, much less to spin others out of the air. I actually found myself working on an airplane last night instead of gazing out the window and reveling in the view, which is what I usually do when flying.

While the hubbub caused by Pops will die down fairly soon, I’m still going to be busy, and though I want to be busy, I’m not at all sure how busy I want to be. In a perfect world I’d settle for a single career, but one of the reasons why I do all the different things I do is that none of them pays me quite enough to stay afloat in New York City. Nor would I find it easy to give up any of them, for each is incredibly gratifying and stimulating in its own right.

In addition, I hasten to point out that I have other good reasons for doing all this work. Not only is it gratifying, but it’s also self-propagating: fresh opportunities to do exciting things next year are coming to me because of the exciting things I’m doing now. As a thug in The Long Goodbye explained to Philip Marlowe, “I got to make lots of dough to juice the guys I got to juice in order to make lots of dough to juice the guys I got to juice.” What has vanished along the way, at least for the moment, is the wasted time that is never wasted, the fallow idleness that eventually bears unforeseen fruit. Will my imagination dry up a year from now because I was too busy to daydream today? I wonder.

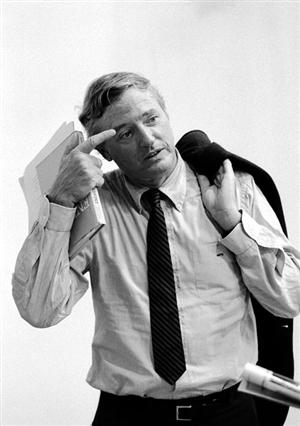

In 1971 Bill Buckley wrote a book called Cruising Speed in which he described a week in his own horrendously crowded life. At the end he pauses for a moment to consider a letter he had just received from “Herbert,” a historian who urged him to turn from his incessant public pursuits and spend more time in intellectual contemplation. “What will be your thoughts,” Herbert wrote, “if when you come to your deathbed you look back and realize that all your life amounted to no more than one big highly successful game of power and self-glorification?”

In 1971 Bill Buckley wrote a book called Cruising Speed in which he described a week in his own horrendously crowded life. At the end he pauses for a moment to consider a letter he had just received from “Herbert,” a historian who urged him to turn from his incessant public pursuits and spend more time in intellectual contemplation. “What will be your thoughts,” Herbert wrote, “if when you come to your deathbed you look back and realize that all your life amounted to no more than one big highly successful game of power and self-glorification?”

The letter brought Bill up short, and caused him to ask of himself the hard questions that can be found in the penultimate paragraph of Cruising Speed:

Herbert is hauntingly right–c’est que la vérité qui blesse–what are my reserves? How will I satisfy them, who listen to me today, tomorrow? Hell, how will I satisfy myself tomorrow, satisfying myself so imperfectly, which is not to say insufficiently, today; at cruising speed?

I have been no less haunted by that passage ever since I first read it years ago. It never occurred to me to ask Bill about it–I didn’t know him well enough–but I wondered when he died in 2008 whether he was still asking himself the same questions. I’m asking them of myself now, and so far I don’t have any answers, good or bad.